Kit Carson

After collecting beavers from traps, he had to hold onto them for months at a time until the annual Rocky Mountain Rendezvous,[19] held in remote areas of the West like the banks of the Green River in Wyoming.

[33] On the way to California, the party suffered from bad weather in the Sierra Nevada Mountains but was saved by Carson's good judgment and his skills as a guide; they found American settlers who fed them.

On April 5, 1846, Frémont's party spotted a Wintu village and launched an unprovoked attack, killing 120 to 300 men, women, and children, and displacing many more in what is known as the Sacramento River massacre.

He ordered Carson to kill an old Mexican man, José de los Reyes Berreyesa, and his two adult nephews, who had been captured when they stepped ashore at San Francisco Bay to prevent them from notifying Mexico about the uprising.

He was dispatched a third time as government courier leaving Los Angeles in May 1848 via the Old Spanish Trail and reached Washington, D.C., with important military messages, which included an official report of the discovery of gold in California.

On the night of December 8, Carson, a naval lieutenant, Edward Fitzgerald Beale, and an Indian scout left Kearny to bring reinforcements from San Diego, 25 miles (40 km) away.

Upon his arrival in Sacramento, he was surprised to learn of his elevation, again, to a hero of the Conquest of California; over the rest of his life he was recognized as a celebrated frontiersman, an image developed by publications of varied accuracy.

"[65] Similarly, Emerson Bennett (1822–1905), a prolific novelist of sensational romances, wrote an overland trail account where a fictional Carson joins a California bound wagon train.

The novelists' gruesome, gory and sensationalized woolly West descriptions would keep readers turning the pages, and buying more buckets-of-blood fictional accounts of Carson, especially during the coming age of dime novels.

In 1849, as he moved to civilian life at Taos and Rayado, Carson was asked to guide soldiers on the trail of White, her baby daughter, and "negro servant", who had been captured by Jicarilla Apaches and Utes.

[69] A soldier in the rescue party wrote: "Mrs. White was a frail, delicate, and very beautiful woman, but having undergone such usage as she suffered nothing but a wreck remained; it was literally covered with blows and scratches.

He wrote in his Memoirs: "In camp was found a book, the first of the kind I had ever seen, in which I was made a great hero, slaying Indians by the hundreds, and I have often thought that Mrs. White would read the same, and knowing that I lived near, she would pray for my appearance and that she would be saved.

[73] In 1858, Dr. DeWitte Clinton Peters (1829–1876), a U. S. Army surgeon who had met Carson in Taos, acquired the manuscript and with Charles Hatch Smith (1829–1882), a Brooklyn lawyer turned music teacher, sometime preacher, and author[74] rewrote it for publication.

The great house of inexpensive novels and questionable nonfiction, Beadle's Dime Library, in 1861, brought out The Life and Times of Kit Carson, the Rocky Mountain Scout and Guide by Edward S. Ellis, one of the stable of writers used by the firm.

[83] By the 1880s, the shoot-em-up gunslinger was replacing the frontiersman tales, but of those in the new generation, one critic notes, "where Kit Carson had been represented as slaying hundreds of Indians, the [new] dime novel hero slew his thousands, with one hand tied behind him.

In fiction, according to historian of literature Richard Etulain, "the small, wiry Kit Carson becomes a ring-tailed roarer, a gigantic Samson...a strong-armed demigod [who] could be victorious and thus pave the way for western settlement.

By the late 1850s, he recommended, to make way for the increasing number of white settlers, that they should give up hunting and become herders and farmers, be provided with missionaries to Christianize them, and move onto reserves in their homeland but distant from settlements with their bad influence of ardent spirits, disease, and unscrupulous Hispanos and Anglos.

Some of those officers were then serving in New Mexico Territory and included James Longstreet and Richard S. Ewell, both of whom gained senior rank in the Army of Northern Virginia, and Henry Hopkins Sibley.

He decided to avoid fighting the Texans in the open field and strengthened the stone and adobe walls of his southern bastion, Fort Craig (about one hundred miles north of Mesilla).

In January 1862, concluding that the Texans would invade northward up the Rio Grande River Valley, Canby consolidated most of his regular infantry and New Mexico volunteer regiments at Fort Craig.

Before Carson arrived at Fort Stanton, Company H, commanded by Captain James Graydon, encountered a band of about thirty Mescalero Apache Indians under chiefs Manuelito and Jose Largo at Gallinas Springs on October 20, 1862.

However, the shock of these killings, along with the fight between two companies of the First California Volunteer Cavalry from Fort Fillmore and a band of Apaches in Dog Canyon near Alamogordo, induced most of the surviving Mescalero chiefs to surrender to Carson.

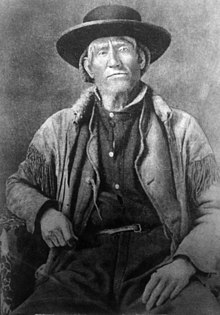

Colonel Edward W. Wynkoop wrote: "Kit Carson was five feet five and one half-inches tall, weighed about 140 pounds, of nervy, iron temperament, squarely built, slightly bow-legged, and those members apparently too short for his body.

His face was fair and smooth as a woman's with high cheekbones, straight nose, a mouth with a firm, somewhat sad expression yet kissable lips, a keen, deep-set but beautiful, mild blue eye, which could become terrible under some circumstances, and like the warning of the rattlesnake, gave notice of attack.

In fact, the hero of a hundred desperate encounters, whose life had been mostly spent amid wilderness, where the white man is almost unknown, was one of Dame Nature's gentleman...."[103] Carson joined Freemasonry in the Santa Fe Territory of New Mexico, petitioning in Montezuma Lodge No.

[121] The first Kit Carson monument, erected in Santa Fe in 1885 at the federal courthouse, was a simple stone obelisk with inscriptions including the words "pathfinder, pioneer, soldier", and "He Led the Way".

For example, the DAR guides noted the monument to Carson at Santa Fe and his and Josefa's home in Taos and the nearby cemetery, where his grave had been marked by the Grand Army of the Republic.

To Smith, Carson represented the symbolic mountain man image created first in the novels of James Fenimore Cooper's Leatherstocking Tales, the pathfinder who went into the wilderness as advance pioneer for civilization.

Smith details the creation of mythic Carson as a national hero, as well as "Indian fighter, the daredevil horseman, the slayer of grizzly bears, the ancestor of the hundreds of two-gun men who came later decades to people the Beadle dime novels".

"[144] In 2000, David Roberts wrote, "Carson's trajectory, over three and a half decades, from thoughtless killer of Apaches and Blackfeet to defender and champion of the Utes, marks him out as one of the few frontiersmen whose change of heart toward the Indians, born not of missionary theory but of first-hand experience, can serve as an exemplar for the more enlightened policies that sporadically gained the day in the twentieth century.