Kobold

Likewise the resident Chimmeken of Mecklenburg Castle, in 1327, allegedly chopped up a kitchen boy into pieces after he took and drank the milk offered to the sprite, according to an anecdote recorded by historian Thomas Kantzow (d. 1542).

[26] The etymology of kobold that Grimm supported derived the word from Latin cobalus (Greek κόβαλος, kobalos),[27] but this was also Georg Agricola's Latin/Greek cypher for kobel, syn.

It is a relatively late vocabularius where kobelte is glossed as (i.e., analogized as) the Roman house and hearth deities "Lares" and Penates, as in Trochus (1517),[26] or "kobold" with "Spiritus familiaris" as in Steier (1705).

[6][49] Otto Schrader also observed that "cult of the hearth-fire" developed into "tutelary house deities, localized in the home", and the German kobold and the Greek agathós daímōn both fit this evolutionary path.

The scenario conjectured by Grimm (seconded by Karl Simrock in 1855) was that home sprites used to be carved from wood or wax and set up in the house, as objects of earnest veneration, but as the age progressed, they degraded into humorous or entertaining pieces of décor.

[Cretin] Schretzelein[107] C. a) [Apparel] Hüdeken[108] b) [Beastform] Hinzelmann,[110] Kazten-veit[111] D. [Noise] Klopfer[113] E. [Person name] Chimmeken[115] Woltken, Chimken[117] Niß-Puk[119][s] G. [Demon] Puk[121] H. [Literary] Heinzelmänchen [122] I.

[6] Grimm, after stating that the list of kobold (or household spirit) in German lore can be long, also adds the names Hütchen and Heinzelmann.

[4][135] Ranke suggests the meaning of Klotz ("klutz, hunk of wood") or a "small being", with a "noisemaker ghost" is possible by descent from MHG bôzen "to beat, strike".

[139] Grimm knew the term but placed the discussion of it under the "Wild man of the woods" section[140] conjecturing the use of güttel as synonymous to götze (i.e., sense of 'idol') in medieval heroic legend.

[144] Since the mandrake do not natively grown in Germany, the so-called Alrune dolls were manufactured out of the available roots such as bryony of the gourd family, gentian, and tormentil (Blutwurz).

[4] However, the term Schrat and its variants has remained current in the sense of "house spirit" only in certain parts such as "southeast Germany": more specifically northern Bavaria including the Upper Palatinate, Fichtel Mountains, Vogtland (into Thuringia), and Austria (Styria and Carinthia) according to the various sources the HdA cites.

[156] There exists a version of this water-bear tale, set in Bad Berneck im Fichtelgebirge, Upper Franconia, where a holzfräulein has been substituted for the schrätel, and the haunting occurring at a miller's, and the "big cat" dispatching the spirit.

[157] Still, the forms schrezala and schretselein seemed to be current around Fichtelgebirge (Fichtel Mountains), or at least in Upper Franconia region as a sprite haunting a house or stable.

§ Cat-shape, below),[169] The HdA does not explicitly include the child-sprite Heintzlein (Heinzlein) mentioned by Martin Luther in his Table Talk, which turns out to be the spirit of the unwanted child murdered by its mother (a motif seen by kobolds elsewhere).

At night, such kobolds do chores that the human occupants neglected to finish before bedtime:[230] They chase away pests, clean the stables, feed and groom the cattle and horses, scrub the dishes and pots, and sweep the kitchen.

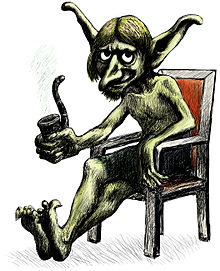

§ True identity as child's ghost Other tales describe kobolds appearing as herdsmen looking for work[228] and little, wrinkled old men in pointed hoods.

[269] The tale of pûks told in Swinemünde (now Świnoujście)[ah] held that a man's luck ran out when he rebuilt his house and the blessing passed on to his neighbor who reused the old beams.

140–141, via Dobeneck.[275][276] Saintine follows the story above with a piece of lore that kobolds are regarded as (ghosts of) infants, and the tail ("caudal appendage") that they have represent the knife used to kill them.

[254] The lore that the kobold's true identity is the soul of a child who died unbaptized was current in the Vogland (including such belief held for the gutel of Erzgebirge).

When a man threw ashes and tares about to try to see King Goldemar's footprints, the kobold cut him to pieces, put him on a spit, roasted him, boiled his legs and head, and ate him.

[124] A legend from the same period taken from Pechüle, near Luckenwald, says that a drak (apparently corrupted from Drache meaning "drake" or "dragon"[289]) or kobold flies through the air as a blue stripe and carries grain.

And the cited story of the Feuermann (Lausitz legend) explains it to be a wood-kobold (Waldkobold) which sometimes entered houses and dwelled in the fireplace or chimney, like the Wendish "drake".

The hinzelmann besides the cat appears as a "dog, hen, red or black bird, buck goat, dragon, and a fiery or bluish form", according to an old encyclopedic entry.

[315][316] In the story of the Chimmeken of the Mecklenburg Castle, (supra, dated 1327 given by Kantzow) the milk customarily put for the sprite by the kitchen was stolen by a kitchen-boy (Küchenbube), and the spirit consequently left the boy's dismembered body in a kettle of hot water.

[339] As a sort of the reverse of the offering, one tradition claims that the kobold will strew wood chips (sawdust, Sägespäne) about the house and putting dirt or cow manure in the milk cans.

[342] According to the lore from South Tyrol (now part of Italy), the Stierl farmstead at Unterinn [de] experienced the trouble where the farmer's wife could not make butter for all her churning in the bucket (Kübel).

In the tale from Nordmohr/Nortmoor, E. Friesland, now Low Saxony) despite standing only about a foot tall, the creature could carry a load of rye in his mouth for the people with whom he lived and did so daily as long as he received a meal of biscuits (Zwieback) and milk.

[356] Insulting a kobold may drive it away, but not without a curse; when someone tried to see his true form, Goldemar left the home and vowed that the house would now be as unlucky as it had been fortunate under his care.

[373] British antiquarian Charles Hardwick ventured a theory that the spirits like the kobold in other cultures, such as the Scottish bogie, French goblin, and English Puck were also etymologically related.

In the novel American Gods, by Neil Gaiman, Hinzelmann is portrayed as an ancient kobold[51] who helps the city of Lakeside in exchange for killing one teenager once a year.