Diponegoro

During his youth at the Yogyakarta court, major occurrences such as the dissolution of the VOC, the British invasion of Java, and the subsequent return to Dutch rule took place.

During the invasion, Sultan Hamengkubuwono III pushed aside his power in 1810 in favor of Diponegoro's father and used the general disruption to regain control.

[6]: 52 Mount Merapi's eruption in 1822 and a cholera epidemic in 1824 furthered the view that a cataclysm was imminent, eliciting widespread support for Diponegoro.

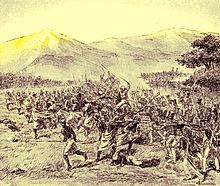

[2] The beginning of the war saw large losses on the side of the Dutch, due to their lack of coherent strategy and commitment in fighting Diponegoro's guerrilla warfare.

The Dutch finally committed themselves to control the spreading rebellion by increasing the number of troops and sending General De Kock to stop the insurgency.

Heavily fortified and well-defended soldiers occupied key landmarks to limit the movement of Diponegoro's troops while mobile forces tried to find and fight the rebels.

From 1829, Diponegoro definitively lost the initiative and he was put in a defensive position; first in Ungaran, then in the palace of the Resident in Semarang, before finally retreating to Batavia.

The imagery of the event, by Javanese Raden Saleh and Dutch Nicolaas Pieneman, depicted Diponegoro differently – the former visualizing him as a defiant victim, the latter as a subjugated man.

[12] After several years in Manado, he was moved to Makassar in July 1833 where he was kept within Fort Rotterdam due to the Dutch believing that the prison was not strong enough to contain him.

Despite his prisoner status, his wife Ratnaningsih and some of his followers accompanied him into exile, and he received high-profile visitors, including 16-year-old Dutch Prince Henry in 1837.

[15] Diponegoro's dynasty would survive to the present day, with their sultans holding secular powers as the governors of the Special Region of Yogyakarta.

In 1969, a large monument Sasana Wiratama was erected in Tegalrejo, in Yogyakarta city's perimeter, with sponsorship from the military where Diponegoro's palace was believed to have stood, although at that time there was little to show for such a building.

[19] Early Islamist political parties in Indonesia, such as the Masyumi, portrayed Diponegoro's jihad as a part of the Indonesian national struggle and by extension Islam as a prominent player in the formation of the country.

The kris of Prince Diponegoro represents a historic importance, as a symbol of Indonesian heroic resilience and the nation's struggle for independence.

(Collection Leiden University Library )