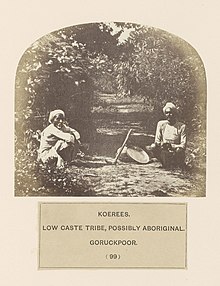

Koeri

[8][9][10] Bihar's land reform drive of 1950s benefitted the groups like Koeris, and they were able to consolidate their landholdings at the cost of big landlords, whose possession witnessed a liquidation.

Haruka Yanagisawa, Professor Emeritus of the University of Tokyo mentions in his work that Koeris along with Yadav and Kurmis were classified as upper-middle caste, who were known for their sturdy and hardy nature.

[16] Koeris have traditionally been classified as a “shudra“[17][18] caste and today Koeris have attempted Sanskritisation—the attempt by traditionally middle and low castes to rise up the social ladder, often by tracing their origins to mythical characters or following the lifestyle of higher varna, such as following vegetarianism, secluding women, or wearing Janeu, the sacred thread.

[19] The Sanskritising trend in castes of northern India, including that of the Koeris, was inspired by the vaishnavite tradition, as attested by their bid to seek association with avatars of Vishnu.

Author William Pinch wrote: "The nineteenth century antecedents of the Kushvaha- kshatriya movement reveal distinct cosmological associations with Shiva and his divine consort, Parvati.

Kushvaha-kshatriya identity was espoused by agricultural community well known throughout the Gangetic north for an expertise in vegetable and (to an increasingly limited scale after the turn of twentieth century) poppy cultivation.

[21] Some Kushwaha reformers like Ganga Prasad Gupta in Banaras argued the Koeris descended from Kusha and that they served Raja Jayachandra in their military capacity during the period of Muslim consolidation under Shuhabuddin Ghuri.

He argued further that after defeat, the fear of persecution at the hands of Muslims caused the Kusvaha Kshatriya to flee into the forest in disarray and discard their sacred threads, so as not to appear as erstwhile defenders of Hinduism.

Writing eighty years later, Francis Buchanan-Hamilton records that Koeris of Bihar were followers of Dashanami Sampradaya while those of Gorakhpur and Ayodhya looked towards Ramanandi saints for spiritual guidance.

The All India Kushwaha Kshatriya Mahasabha was formed to bring the horticulturist and market gardener communities like the Koeri, the Kachhi and the Murao under one umbrella.

[26] Describing the industrious nature of the Koeri people, Susan Bayly wrote: "By the mid-nineteenth century, influential revenue specialists were reporting that they could tell the caste of a landed man by simply glancing at his crops.

Similar virtues would be found among the smaller market-gardening populations, these being the people known as Koeris in Hindustan"[27]Colonial ethnographers like Dr. Hunter identified Koiris and Oudhia Kurmis as most respectable of all cultivating castes in some districts of Bihar.

[28] In 1877, there was an attempt by colonial Government of Bengal to prepare an account of Indian society and it culminated into the process of all india social classification of various castes and tribes beginning with the first census of 1871.

In 1901, Herbert Hope Risley applied anthropometrical methods to develop a racial taxonomy of Indian society leading to a problematic attempt to classify people of India.

[29] An official report of 1941 described them as being the "most advanced" cultivators in Bihar and said, "Simple in habits, thrifty to a degree and a master in the art of market-gardening, the Koeri is amongst the best of the tillers of the soil to be found anywhere in India.

[29] In the early 19th century in the Gaya district, Koeris were recorded by Francis Buchanan as a community of "ploughing tribes" consisting primarily of poor and middle peasants.

It was however noted that in his survey, Buchanan had neglected an upper crust among them, which had accumulated and hoarded cash and had emerged as moneylenders forwarding Kamiauti advances to acquire dependent labour.

[6] Malabika Chakrabarti also mentions that better-off peasants of Koeri caste in region of South Bihar supplemented their income from cultivation by working as Mahajan or moneylenders.

[12] The diversification in occupation of the Koeri caste in post independence India is shown by studies in select villages of North Bihar.

Kumar's study found that both these caste compete for political power in these zones and a few Koeri families, who are economically sound, also own the local Primary Agricultural Credit Societies and Public Distribution System.

[37] Sanjay Kumar associates the political mobilisation of the middle peasant castes, also called upper-OBCs with this gradual process of land reforms undertaken in Bihar in the decades preceding the period of 1970-90.

This was witnessed in Ekwari, a village, in the Bhojpur district where Jagdish Mahto, a Koeri teacher, began leading the Maoists and organised the murders of upper caste landlords after he was beaten up by Bhumihars for supporting the Communist Party of India (CPI) in the 1967 elections to Bihar Legislative Assembly.

Though the island is divided along ethnic and religious lines, 'Hindu' Mauritians follow a number of original customs and traditions, quite different from those seen on the Indian subcontinent.

Here, both male and female members of the family participated in cultivation- related operations, thus paving the way for egalitarianism and a lack of gender-related discrimination and seclusion.

Prominent Jharkhand leaders like Aklu Ram Mahto, Dev Dyal Kushwaha and Bhubneshwar Prasad Mehta had remained associated with this organisation in past.

[60] In the early twentieth century, the Koeri and their sub-caste the Murao participated in the politics of the Kisan Sabha, which worked for the peasants' cause against the ill effects of landlordism and the 1920 Gandhian non-cooperation movement.

The traditional method of Nai-Dhobi band—disallowing of service of washermen and barbers to enforce the sanctions on the landlords and use of their robust caste panchayats—became a symbol of this peasant movement.

[61][62][63] In the heyday of British Raj, the Koeris aligned with the Kurmis and the Yadavs to form a caste coalition-cum-political party called Triveni Sangh.

The Congress's reliance on its "Coalition Of Extremes", referring to the alliance of Upper Castes, Dalits and Muslims became the prime reason behind the upper-OBC's drive for alternative route to gain political ascendency.

The Bharatiya Janata Party appealed to the kushwaha in the 2014 elections in hopes of getting the support of the Koeri caste who had earlier voted for Nitish Kumar and the JD(U).