Kohala (mountain)

Toward the end of its shield-building stage 250,000 to 300,000 years ago, a landslide destroyed the northeast flank of the volcano, reducing its height by over 1,000 m (3,300 ft) and traveling 130 km (81 mi) across the sea floor.

[citation needed] Crops, especially sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), have been cultivated on the Leeward side of the volcano for centuries.

Beginning 300,000 years ago, the rate of eruption slowly decreased over a long period of time to a point where erosion wore the volcano down faster than Kohala rebuilt itself through volcanic activity.

[1][4] However, based on a sharp increase of incline on the submarine slope of the volcano at a depth of 1,000 m (3,300 ft), scientists estimate that in its prime the portion of Kohala that was above the water was more than 50 km (31 mi) wide.

Fifty flow units in the top 140 m (460 ft) of exposed strata in the Pololu section are of normal polarity, indicating that they were deposited within the last 780,000 years.

Radiometric dating ranged mostly from 450,000 to 320,000 years ago, although several pieces strayed lower; this indicated a period of eruptive history at the time.

The famous sea cliffs of the windward Kohala shoreline stand as evidence of the massive geologic disaster, and mark the topmost part of the debris from this ancient landslide.

A research team led by University of Hawaii's Gary McMurtry and Dave Tappin of the British Geological Survey found that the fossils had been deposited by a massive tsunami, 61 m (200 ft) above the current sea level.

Based on the rate of Kohala's subsidence over the past 475,000 years, it was estimated that the fossils were deposited at a height of about 500 m (1,600 ft), well out of reach of storms and far above the normal sea level at the time.

Researchers hypothesize that the underwater landslide from the nearby volcano triggered a gigantic tsunami, which swept up coral and other small marine organisms, depositing them on the western face of Kohala.

The rock in the younger Hawi section, which overlies the older Pololu flows, is mostly 260,000 to 140,000 years old, and composed mainly of hawaiite and trachyte.

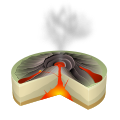

[10] Kohala, like other shield volcanoes, has a shallow surface slope due to the low viscosity of the lava flows that formed it; however, the northwest shoreline boasts some of the highest seacliffs on Earth.

Events during and after its eruptions give the volcano several unique geomorphic features, some possibly resulting from the ancient collapse and landslide.

[12] The windward side of Kohala mountain is dissected by multiple, deeply eroded stream valleys in a southwest–northeast alignment, cutting into the flanks of the volcano.

[14] Waimanu valley, cut off from its headwaters to the summit and left with Wai'ilikahi as its main tributary, still had managed to form a substantial floodplain, although less than half the size of Waipiʻo.

Recent seafloor mapping seems to show that the valley extends a short way beyond the seashore, then terminates at what may be the headwall of the great landslide found off the northeast coast of Kohala.

[3] In addition to being a primary factor in the development of the largest valleys, the dike complex plays another important role —that of creating and maintaining the water table.

Due to its topography as essentially a flat crater floor surrounded by cones and fault scarps, the main caldera is affected relatively little by erosion from water.

Surface water supplies, however, were not stable enough for the large scale plantation economy developing in Hamakua and North Kohala, so later ditches tapped the spring fed base flows of the valleys and larger gulches.

[21] The happy combination of small trees, bushes, ferns, vines, and other forms of ground cover keep the soil porous and allow the water to percolate more easily into underground channels.

A considerable portion of the precipitation is let down to the ground slowly by this three-story cover of trees, bushes, and floor plants and in this manner the rain, falling on a well-forested area, is held back and instead of rushing down to the sea rapidly in the form of destructive floods, is fed gradually to the springs and to the underground artesian basins where it is held for use over a much longer interval...[15] The forest lies perpendicular to the prevailing trade winds, a characteristic that leads to frequent cloud formation and abundant rainfall.

"[15] Before humans arrived, the wildlife population at Kohala and on the rest of the island was isolated from other species, as it was separated from the nearest major landmass by over 2,000 mi (3,200 km) of open water.

Kohala's bogs are characterized by sedges, mosses of the genus Sphagnum, and oha wai, native members of the bellflower family.

[15] Kohala's native Hawaiian rain forest has a thick layer of ferns and mosses carpeting the floor, which act as sponges, absorbing water from rain and passing much of it through to the groundwater in aquifers below; when feral animals like pigs trample the covering, the forest loses its ability to hold in water effectively, and instead of recharging the aquifer, it results in a severe loss of topsoil, much of which ends up being dumped by streams into the ocean.

From 1400 to 1800, the principal crop grown at Kohala was sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), although there is also evidence of yams (Dioscorea sp.

In addition, Kohala is buffeted by strong winds, which are directly correlated to soil erosion; ancient farmers utilized a series of earthen embarkments and stone walls to protect their crops.

[23] At the peak of its production, the company had 600 employees, 13,000 acres (20 sq mi) of land, and a capacity of 45,000 t (99,000,000 lb) of raw sugar per year.

In the early part of the 20th century, this was exploited by building surface irrigational channels designed to capture water at the higher elevations and distribute it to the then-extensive sugarcane industry.

It was established as a response to requests by island residents to create an educational and employment opportunity related to Hawaii's natural and cultural significance.

The center's mission is "to respectfully engage the Island of Hawaiʻi as an extraordinary and vibrant research and learning laboratory for humanity.