Byzantine Empire under the Komnenos dynasty

1054), Byzantium experienced several decades of stagnation and decline, which culminated in a vast deterioration in the military, territorial, economic and political situation of the Byzantine Empire by the accession of Alexios I Komnenos in 1081.

Beginning with the death of the successful soldier-emperor Basil II in 1025, a long series of weak rulers had disbanded the large armies which had been defending the eastern provinces from attack; instead, gold was stockpiled in Constantinople, ostensibly in order to hire mercenaries should troubles arise.

In 1040, the Normans, originally landless mercenaries from northern parts of Europe in search of plunder, began attacking Byzantine strongholds in southern Italy.

[4] With stability at last achieved in the west, Alexios now had a chance to begin solving his severe economic difficulties and the disintegration of the empire's traditional defences.

In order to reestablish the army, Alexios began to build a new force on the basis of feudal grants (próniai) and prepared to advance against the Seljuks, who had conquered Asia Minor and were now established at Nicaea.

This mission was deftly accomplished – at the Council of Piacenza in 1095, Pope Urban II was impressed by Alexios's appeal for help, which spoke of the suffering of the Christians of the east and hinted at a possible union of the eastern and western churches.

Alexios's appeal offered a means not only to redirect the energy of the knights to benefit the Church, but also to consolidate the authority of the Pope over all Christendom and to gain the east for the See of Rome.

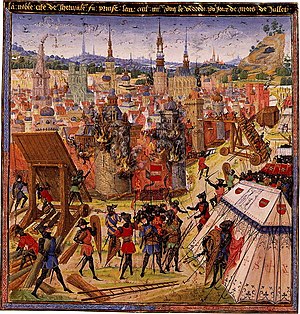

There, amid a crowd of thousands who had come to hear his words, he urged all present to take up arms under the banner of the Cross and launch a holy war to recover Jerusalem and the east from the 'infidel' Muslims.

By their victories, Alexios was able to recover for the Byzantine Empire a number of important cities and islands: Nicaea, Chios, Rhodes, Smyrna, Ephesus, Philadelphia, Sardis, and in fact much of western Asia Minor (1097–1099).

In order to ensure that all taxes were paid in full, and to halt the cycle of debasement and inflation, he completely reformed the coinage, issuing a new gold hyperpyron (highly refined) coin for the purpose.

[5] The final years of Alexios's reign were marked by persecution of the followers of the Paulician and Bogomil heresies—one of his last acts was to burn at the stake the Bogomil leader, Basil the Physician, with whom he had engaged in a theological controversy; by renewed struggles with the Turks (1110–1117); and by anxieties as to the succession, which his wife Irene wished to alter in favour of her daughter Anna's husband Nikephorus Bryennios, for whose benefit the special title panhypersebastos ("honored above all") was created.

[10] After a challenging campaign, the details of which are obscure, the emperor managed to defeat the Hungarians and their Serbian allies at the fortress of Haram or Chramon, which is the modern Nova Palanka.

In order to restore the region to Byzantine control, John led a series of campaigns against the Turks, one of which resulted in the reconquest of the ancestral home of the Komneni at Kastamonu.

Yet resistance, particularly from the Danishmends of the north-east, was strong, and the difficult nature of holding down the new conquests is illustrated by the fact that Kastamonu was recaptured by the Turks whilst John was back in Constantinople celebrating its return to Byzantine rule.

Unlike Romanos Diogenes, John's forces were able to maintain their cohesion, and the Turkish attempt to inflict a second Manzikert on the emperor's army backfired when the Sultan, discredited by his failure, was murdered by his own people.

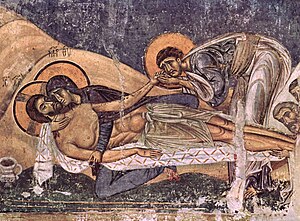

[14] Ultimately, Joscelin and Raymond conspired to keep John out of Antioch, and while he was preparing to lead a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and a further campaign, he accidentally grazed his hand on a poison arrow while out hunting.

Substantial territories had been recovered, and his successes against the invading Petchenegs, Serbs and Seljuk Turks, along with his attempts to establish Byzantine suzerainty over the Crusader States in Antioch and Edessa, did much to restore the reputation of his empire.

His careful, methodical approach to warfare had protected the empire from the risk of sudden defeats, while his determination and skill had allowed him to rack up a long list of successful sieges and assaults against enemy strongholds.

His early death meant his work went unfinished; historian Zoe Oldenbourg speculates that his last campaign might well have resulted in real gains for Byzantium and the Christian cause.

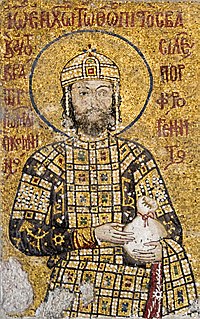

Manuel himself is generally considered the most brilliant of the four emperors of the Komnenos dynasty; unusual for a Byzantine ruler, his reputation was particularly good in the west and the Crusader states, especially after his death.

[13] Manuel campaigned aggressively against his neighbours both in the west and in the east; facing Muslims in Palestine, he allied himself with the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem and sent a large fleet to participate in a combined invasion of Fatimid Egypt.

Manuel demanded tribute from the Turkmen of the Anatolian interior for the winter pasture in Imperial territory; he also improved the defenses of many cities and towns, and established new garrisons and fortresses across the region.

As historian Paul Magdalino makes clear, "by the end of Manuel's reign, the Byzantines controlled all the rich agricultural lowlands of the peninsula, leaving only the less hospitable mountain and plateau areas to the Turks.

[7] Alongside troops raised and paid for directly by the state, the Komnenian army included the armed followers of members of the wider imperial family and its extensive connections.

[7] As Byzantine Asia Minor began to prosper under John and Manuel, more soldiers were raised from the Asiatic provinces of Neokastra, Paphlagonia and even Seleucia (in the south east).

[4] The main Anatolian camp was near Lopadion on the Rhyndakos River near the Sea of Marmora, the European equivalent was at Kypsella in Thrace, others were at Sofia (Serdica) and at Pelagonia, west of Thessalonica.

[13] Although the term does not enjoy widespread usage, it is beyond doubt that 12th century Byzantium witnessed major cultural developments, which were largely underpinned by rapid economic expansion.

The 12th century was a time of significant growth in the Byzantine economy, with rising population levels and extensive tracts of new agricultural land being brought into production.

Alexios II was compelled to acknowledge Andronikos as colleague in the empire, but was then put to death; the killing was carried out by Tripsychos, Theodore Dadibrenos and Stephen Hagiochristophorites.

[29] In particular, Andonikos's failure to prevent the massacre of Latins in Constantinople in 1182 has been seen as especially significant, since henceforth Byzantine foreign policy was invariably perceived as sinister and anti-Latin in the west.