Krak des Chevaliers

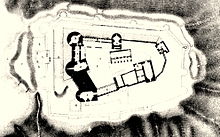

Renewed interest in Crusader castles in the 19th century led to the investigation of Krak des Chevaliers, and architectural plans were drawn up.

Since 2006, the castles of Krak des Chevaliers and Qal'at Salah El-Din have been recognised by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites.

[13] Compared to the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the other Crusader states had less land suitable for farming; however, the limestone peaks of Tripoli were well-suited to defensive sites.

[13] According to the 13th-century Arab historian Ibn Shaddad, in 1031, the Mirdasid emir of Aleppo and Homs, Shibl ad-Dawla Nasr, established a settlement of Kurdish tribesmen at the site of the castle,[15] which was then known as "Ḥiṣn al-Safḥ".

[15][16] The castle was strategically located at the southern edge of the Jibal al-Alawiyin mountain range and dominated the road between Homs and Tripoli.

Early donations were in the newly formed Kingdom of Jerusalem, but over time the order extended its holdings to the Crusader states of the County of Tripoli and the Principality of Antioch.

[23] The Hospitallers made Krak des Chevaliers a center of administration for their new property, undertaking work at the castle that would make it one of the most elaborate Crusader fortifications in the Levant.

The proximity of Krak des Chevaliers to Muslim territories allowed it to take on an offensive role, acting as a base from which neighboring areas could be attacked.

By 1203, the garrison was making raids on Montferrand (which was under Muslim control) and Hama, and in 1207 and 1208 the castle's soldiers took part in an attack on Homs.

A Muslim army estimated to number 10,000 men ravaged the countryside around the castle in 1252, after which the Order's finances declined sharply.

In 1268, Master Hugues Revel complained that the area, previously home to around 10,000 people, now stood deserted and that the Order's property in the Kingdom of Jerusalem produced little income.

As a result, Muslim settlements that had previously paid tribute to the Hospitallers at Krak des Chevaliers no longer felt intimidated into doing so.

[citation needed] Baibars ventured into the area around Krak des Chevaliers in 1270 and allowed his men to graze their animals on the fields around the castle.

When he received news that year of the Eighth Crusade led by King Louis IX of France, Baibars left for Cairo to avoid a confrontation.

In a probable reference to a walled suburb outside the castle's entrance, Ibn Shaddad records that two days later the first line of defences fell to the besiegers.

[38] Rain interrupted the siege, but on 21 March, immediately south of Krak des Chevaliers, Baibar's forces captured a triangular outwork possibly defended by a timber palisade.

After a lull of ten days, the besiegers conveyed a letter to the garrison, supposedly from the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller in Tripoli, which granted permission, (aman), for them to surrender on 8 April 1271.

Several Turkmen and Kurdish tribes were settled in the area, and in the 18th century the district was mainly controlled by local notables from the Dandashi family.

In 1894, the Ottoman government considered stationing a company of auxiliary soldiers there, but revised its plans after deciding the castle was too old and access too difficult.

Deschamps and fellow architect François Anus attempted to clear some of the detritus; General Maurice Gamelin assigned 60 Alawite soldiers to help.

Kennedy suggests that "The castle scientifically designed as a fighting machine surely reached its apogee in great buildings like Margat and Crac des Chevaliers.

[60] The main building material at Krak des Chevaliers was limestone; the ashlar facing is so fine that the mortar is barely noticeable.

In this area, the walls were supported by a steeply sloping glacis which provided additional protection against both siege weapons and earthquakes.

The esplanade is raised above the rest of the courtyard; the vaulted area beneath it would have provided storage and could have acted as stabling and shelter from missiles.

[41] The later chapel had a barrel vault and an uncomplicated apse; its design would have been considered outmoded by contemporary standards in France, but bears similarities to that built around 1186 at Margat.

The outer walls were built in the last major construction on the site, lending the Krak des Chevaliers its current appearance.

The box machicolations were unusual: those at Krak des Chevaliers were more complex that those at Saône or Margat, and there were no comparable features amongst Crusader castles.

It is unclear which side imitated the other, as the date they were added to Krak des Chevaliers is unknown, but it does provide evidence for the diffusion of military ideas between the Muslim and Christian armies.

In the opinion of historian Hugh Kennedy, the defences of the outer wall were "the most elaborate and developed anywhere in the Latin east ... the whole structure is a brilliantly designed and superbly built fighting machine".

Writing in 1982, historian Jaroslav Folda noted that at the time there had been little investigation of Crusader frescoes that would provide a comparison for the fragmentary remains found at Krak des Chevaliers.

Translation:

You may have bounty, you may have wisdom, you may be granted beauty; pride alone defiles all [these things] if it accompanies [them].