Kreutz sungrazer

They are believed to be fragments of one large comet that broke up several centuries ago and are named for German astronomer Heinrich Kreutz, who first demonstrated that they were related.

Several members of the Kreutz family have become great comets, occasionally visible near the Sun in the daytime sky.

Amateur astronomers have been successful at discovering Kreutz comets in the data available in real time via the internet.

Some astronomers suggested that perhaps they were all one comet, whose orbital period was somehow being drastically shortened at each perihelion passage, perhaps by retardation by some dense material surrounding the Sun.

[1] This idea was first proposed in 1880, and its plausibility was amply demonstrated when the Great Comet of 1882 broke up into several fragments after its perihelion passage.

[7] The appearance of two Kreutz sungrazers in quick succession inspired further study of the dynamics of the group.

[4] Erosion of the comets by solar energy during close passages leads to progressive changes in their orbits.

[19] The water and organic materials of a comet evaporate first, exposing fluffy aggregations of olivines that form dust tails.

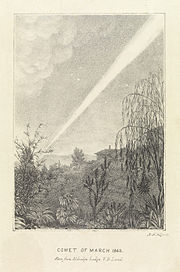

[30] The Great Comet of 1843 was first noticed in early February of that year, just over three weeks before its perihelion passage when it passed about 830,000 kilometres (520,000 mi) from the surface of the Sun.

It extended about 45° across the sky on March 11 and was more than 2° wide;[33] the tail was calculated to be more than 300 million kilometers (2 AU) long.

)[34][35] The comet was very prominent throughout early March, before fading away to almost below naked eye visibility by the beginning of April.

This comet apparently made a substantial impression on the public, inspiring in some a fear that judgement day was imminent.

[2] The Great Comet of 1882 was discovered independently by many observers, as it was already easily visible to the naked eye when it appeared in early September 1882, just a few days before perihelion, at which it reached an apparent magnitude estimated to have been −17, by far the brightest recorded for any comet and exceeding the brightness of the full moon by a factor of 57.

[35] It grew rapidly brighter and was eventually so bright it was visible in the daytime for two days (16–17 September), even through light cloud.

It was discovered independently by two Japanese amateur astronomers on September 18, 1965, within 15 minutes of each other, and quickly recognised as a Kreutz sungrazer.

[2] A few hours before perihelion passage on October 21 it had a visible magnitude from −10 to −11, comparable to the first quarter of the Moon and brighter than any other comet seen since 1882.

[38] A study by Brian G. Marsden in 1967 was the first attempt to trace back the orbital history of the group to identify the progenitor comet.

[5] Marsden found that the Kreutz sungrazers could be split into two groups, with slightly different orbital elements, implying that the family resulted from fragmentations at more than one perihelion.

[40][1] Comet White–Ortiz–Bolelli, which was seen in 1970,[41] is more closely related to this group than Subgroup I, but appears to have broken off during the previous orbit to the other fragments.

This process may occur a few times every million years, which may either be an underestimate or may indicate that humanity is lucky that such a Kreutz sungrazer family exists just now.

[50] Until recently, a very bright member of the Kreutz sungrazers could pass through the inner Solar System unnoticed if its perihelion had occurred between about May and August.

Since the launch of the SOHO Sun-observing satellite in 1995, it has been possible to observe comets very close to the Sun at any time of year.

[6] The satellite provides a constant view of the immediate solar vicinity, and SOHO has now discovered hundreds of new Sun-grazing comets, some just a few metres across.

About 83% of the sungrazers found by SOHO are members of the Kreutz group, with the others including the Meyer, Marsden, and Kracht1&2 families.

[54] Apart from Comet Lovejoy, none of the sungrazers seen by SOHO has survived its perihelion passage; some may have plunged into the Sun itself, but most are likely to have simply evaporated away completely.

These pairs are too frequent to occur by chance, and cannot be due to break-ups on the previous orbit, because the fragments would have separated by a much greater distance.

[6] Dynamically, the Kreutz sungrazers might continue to be recognised as a distinct family for many thousands of years.

[61] In December 2011, Kreutz sungrazer C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy) survived its perihelion passage for some time[62] and had an apparent magnitude of −3.