Kroger Babb

"[2] His films ranged from sex education-style dramas to "documentaries" on foreign cultures, intended to titillate audiences rather than to educate them, maximizing profits via marketing gimmicks.

[2] He started out with jobs in sportswriting and reporting at a local newspaper in his 20s, and even showed signs of his later work while showcasing "Digger" O'Dell, the "living corpse",[5] but first achieved success after his promotion to publicity manager for the Chakeres-Warners movie theaters, where he would create different kinds of stunts to lure audiences[4]—for example, a drawing to award two bags of groceries to one ticket holder at selected theaters.

[2] In the early 1940s Babb joined Cox and Underwood, a company that obtained the rights to poorly made or otherwise unmarketable films of subjects that were potentially controversial or shocking.

[2] He opened it near his childhood home in Wilmington, Ohio, and hired booking agents and advance salesmen along with out-of-work actors and comedians to present repackaged films and new features.

[3] Its success spawned a number of imitations, such as Street Corner and The Story of Bob and Sally, that eventually flooded the market,[1] but it was still being shown around the world decades later[9] and ultimately was added to the National Film Registry in 2005.

Eric Schaefer explains: The film became so ubiquitous that Time said its presentation "left only the livestock unaware of the chance to learn the facts of life".

[7] Babb also made sure that each showing of the film followed a similar format: adults-only screenings segregated by gender, and live lectures by "Fearless Hygiene Commentator Elliot Forbes" during an intermission.

[1] (in some predominantly African-American areas, Olympic gold medalist Jesse Owens appeared instead,[4] a trend he'd continue with films like "She Shoulda Said 'No'!

"[10]) According to entertainer Card Mondor, an Elliot Forbes in the 1940s who later purchased the Australian and New Zealand rights for Mom and Dad, the Forbeses were "mostly local men (from Wilmington, Ohio) who were trained to give the lecture .

[1] David F. Friedman, another successful exploitation filmmaker of the era, has attributed the "one-time-only" distribution to a quality so low that Babb wanted to cash in and move to his next stop as fast as possible.

"[1] Despite the criticism that Babb drew for Mom and Dad, in 1951 he received the first annual Sid Grauman Showmanship Award, presented by the Hollywood Rotary Club in honor of his accomplishments over the years.

Its original producer had struggled to get it distributed as Wild Weed, and Babb quickly presented it as The Story of Lila Leeds and Her Exposé of the Marijuana Racket, hoping that the title would draw audiences.

When it failed to stir up much interest, Babb instead focused on the one scene of female nudity, using a photo of Leeds in a showgirl outfit, and retitled it "She Shoulda Said 'No'!

[3] In addition to re-dubbing it, Babb re-edited and re-titled it The Prince of Peace; it was so successful that the New York Daily News called it "the Miracle of Broadway".

[1] Babb never repeated the overwhelming success of Mom and Dad, and he followed much of the exploitation industry in turning to burlesque features in an attempt to make more money.

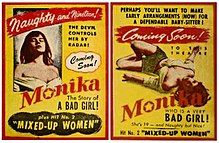

About one-third of the film was cut, and the remaining 62 minutes emphasized nudity by retaining a skinny-dipping scene; the result was titled Monika, the Story of a Bad Girl.

[1] Babb's final film was his presentation of a European version of Harriet Beecher Stowe's book Uncle Tom's Cabin.

This was described by Friedman as one of the most "unintentionally funny exploitation films ever made", filled with "second-rate Italian actors who could barely speak English".

[17] On the strength of his past successes, Babb joined John Miller's film production company, Miller-Consolidated Pictures, as vice president and general manager in 1959.

His personal anecdotes provided advice for selling films, such as writing off expenses as tax deductions, and using women's clubs to expand advertising and revenues cheaply.

Operating in Beverly Hills (and claiming representation in Canada, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand[19]), it used similar roadshow techniques to market television programs such as The Ern Westmore Show.