Kuzari

The Kuzari, full title Book of Refutation and Proof on Behalf of the Despised Religion[1] (Judeo-Arabic: כתאב אלרד ואלדליל פי אלדין אלדׄליל; Arabic: كتاب الحجة والدليل في نصرة الدين الذليل: Kitâb al-ḥujja wa'l-dalîl fi naṣr al-dîn al-dhalîl), also known as the Book of the Khazar (Hebrew: ספר הכוזרי: Sefer ha-Kuzari),[2] is one of the most famous works of the medieval Spanish Jewish philosopher, physician, and poet Judah Halevi, completed in the Hebrew year 4900 (1139-40CE).

Originally written in Arabic, prompted by Halevi's contact with a Spanish Karaite,[3] it was then translated by numerous scholars, including Judah ben Saul ibn Tibbon, into Hebrew and other languages, and is regarded as one of the most important apologetic works of Jewish philosophy.

[2] Divided into five parts (ma'amarim "articles"), it takes the form of a dialogue between a rabbi and the king of the Khazars, who has invited the former to instruct him in the tenets of Judaism in comparison with those of the other two Abrahamic religions: Christianity and Islam.

[4][5][6][7] A minority of scholars, among them Moshe Gil and Shaul Stampfer have challenged the document's claim to represent a real historical event.

[10] Setting aside the possible exception of the work of Maimonides, it had a profound impact on the subsequent development of Judaism,[11][12] and has remained central to Jewish religious tradition.

[13] Given what has been generally regarded as its pronounced anti-philosophical tendencies, a direct line has been drawn, prominently by Gershom Scholem, between it and the rise of the anti-rationalist Kabbalah movement.

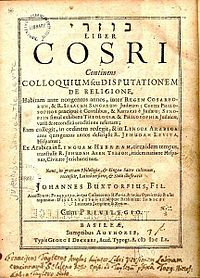

[15] In addition to the 12th-century Hebrew translation by Judah ben Saul ibn Tibbon,[16] which passed through eleven printed editions (1st ed.

The king expresses his astonishment at this exordium, which seems to him incoherent; but the Jew replies that the existence of God, the creation of the world, etc., being taught by religion, do not need any speculative demonstrations.

Halevi writes that as the Jews are the only depositaries of a written history of the development of the human race from the beginning of the world, the superiority of their traditions cannot be denied.

Still, relying upon tradition, the Jews believe in "creatio ex nihilo" which theory can be sustained by as powerful arguments as those advanced in favor of the belief in the eternity of matter.

The objection that the Absolutely Infinite and Perfect could not have produced imperfect and finite beings, made by the Neoplatonists to the theory of "creatio ex nihilo," is not removed by attributing the existence of all mundane things to the action of nature; for the latter is only a link in the chain of causes having its origin in the First Cause, which is God.

The preservation of the Israelites in Egypt and in the wilderness, the delivery to them of the Torah (law) on Mount Sinai, and their later history are to him evident proofs of its superiority.

The question of why the Jews were favored with God's instruction is answered in the Kuzari at I:95: it was based upon their pedigree, i.e., Noah's most pious son was Shem.

The remainder of the essay comprises dissertations on the following subjects: the excellence of Israel, the land of prophecy, which is to other countries what the Jews are to other nations; the sacrifices; the arrangement of the Tabernacle, which, according to Judah, symbolizes the human body; the prominent spiritual position occupied by Israel, whose relation to other nations is that of the heart to the limbs; the opposition evinced by Judaism toward asceticism, in virtue of the principle that the favor of God is to be won only by carrying out His precepts, and that these precepts do not command man to subdue the inclinations suggested by the faculties of the soul, but to use them in their due place and proportion; the excellence of the Hebrew language, which, although sharing now the fate of the Jews, is to other languages what the Jews are to other nations and what Israel is to other lands.

Although he professes great reverence for the "Sefer Yetẓirah," from which he quotes many passages, he hastens to add that the theories of Abraham elucidated therein had been held by the patriarch before God revealed Himself to him.

He shows himself especially severe against the Motekallamin, whose arguments on the creation of the world, on God and His unity, he terms dialectic exercises and mere phrases.