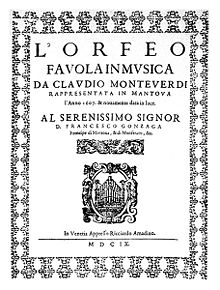

L'Orfeo

It is based on the Greek legend of Orpheus, and tells the story of his descent to Hades and his fruitless attempt to bring his dead bride Eurydice back to the living world.

After training in singing, string playing and composition, Monteverdi worked as a musician in Verona and Milan until, in 1590 or 1591, he secured a post as suonatore di vivuola (viola player) at Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga's court at Mantua.

A century before Duke Vincenzo's time the court had staged Angelo Poliziano's lyrical drama La favola di Orfeo, at least half of which was sung rather than spoken.

[7] On 6 October 1600, while visiting Florence for the wedding of Maria de' Medici to King Henry IV of France, Duke Vincenzo attended the premiere of Peri's Euridice.

Together with Duke Vincent's two young sons, Francesco and Fernandino, he was a member of Mantua's exclusive intellectual society, the Accademia degli Invaghiti [it], which provided the chief outlet for the city's theatrical works.

In a letter written on 5 January, Francesco Gonzaga asks his brother, then attached to the Florentine court, to obtain the services of a high quality castrato from the Grand Duke's establishment, for a "play in music" being prepared for the Mantuan Carnival.

[14] Musicologist Gary Tomlinson remarks on the many similarities between Striggio's and Rinuccini's texts, noting that some of the speeches in L'Orfeo "correspond closely in content and even in locution to their counterparts in L'Euridice".

By contrast, because Striggio was not writing for a formal court celebration he could be more faithful to the spirit of the myth's conclusion, in which Orfeo is killed and dismembered by deranged maenads or "Bacchantes".

He had been employed at the Gonzaga court for 16 years, much of it as a performer or arranger of stage music, and in 1604 he had written the ballo Gli amori di Diane ed Endimone for the 1604–05 Mantua Carnival.

[18] The elements from which Monteverdi constructed his first opera score—the aria, the strophic song, recitative, choruses, dances, dramatic musical interludes—were, as conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt has pointed out, not created by him, but "he blended the entire stock of newest and older possibilities into a unity that was indeed new".

[19] Musicologist Robert Donington writes similarly: "[The score] contains no element which was not based on precedent, but it reaches complete maturity in that recently developed form ...

Despite the five-act structure, with two sets of scene changes, it is likely that L'Orfeo conformed to the standard practice for court entertainments of that time and was played as a continuous entity, without intervals or curtain descents between acts.

[23] For the purpose of analysis the music scholar Jane Glover has divided Monteverdi's list of instruments into three main groups: strings, brass and continuo, with a few further items not easily classifiable.

[5] The Monteverdi scholar Tim Carter speculates that two prominent Mantuan tenors, Pandolfo Grande and Francesco Campagnola may have sung minor roles in the premiere.

Carter calculates that through the doubling of roles that the text allows, a total of ten singers—three sopranos, two altos, three tenors and two basses—is required for a performance, with the soloists (except Orfeo) also forming the chorus.

An instrumental toccata (English: "tucket", meaning a flourish on trumpets)[35] precedes the entrance of La musica, representing the "spirit of music", who sings a prologue of five stanzas of verse.

Orfeo attempts to persuade Caronte by singing a flattering song to him ("Mighty spirit and powerful divinity"), and, although the ferryman is moved by his music ("Indeed thou charmest me, appeasing my heart"), he does not allow him to pass, claiming he is incapable of feeling pity.

Seizing his chance, Orfeo steals the ferryman's boat and crosses the river, entering the Underworld while a chorus of spirits reflects that nature cannot defend herself against man: "He has tamed the sea with fragile wood, and disdained the rage of the winds."

In Striggio's 1607 libretto, Orfeo's act 5 soliloquy is interrupted, not by Apollo's appearance but by a chorus of maenads or Bacchantes—wild, drunken women—who sing of the "divine fury" of their master, the god Bacchus.

[39] However, this alternative ending in any case nearer to original classic myth, where the Bacchantes also appear, but it is made explicit that they torture him to his death, followed by reunion as a shade with Euridice but no apotheosis nor any interaction with Apollo.

The room of the premiere cannot be identified with certainty; according to Ringer, it may have been the Galleria dei Fiumi, which has the dimensions to accommodate a stage and orchestra with space for a small audience.

[46][47][n 5] The distinguished writer Romain Rolland, who was present, commended d'Indy for bringing the opera to life and returning it "to the beauty it once had, freeing it from the clumsy restorations which have disfigured it"—presumably a reference to Eitner's edition.

[52] Westrup's edition was revived in London at the Scala Theatre in December 1929, the same year in which the opera received its first US staged performance, at Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts.

The theatre was criticised by New York Times critic Harold C. Schonberg because, to accommodate a performance of Luigi Dallapiccola's contemporary opera Il prigioniero, about a third of L'Orfeo was cut.

During the period 2008–10, the French-based Les Arts Florissants, under its director William Christie, presented the Monteverdi trilogy of operas (L'Orfeo, Il ritorno d'Ulisse and L'incoronazione di Poppea) in a series of performances at the Teatro Real in Madrid.

Two choruses, one solemn and one jovial are repeated in reverse order around the central love-song "Rosa del ciel" ("Rose of the heavens"), followed by the shepherds' songs of praise.

[72] The sudden entrance of La messaggera with the doleful news of Euridice's death, and the confusion and grief which follow, are musically reflected by harsh dissonances and the juxtaposition of keys.

[72] The centrepiece of act 3, perhaps of the entire opera, is Orfeo's extended aria "Possente spirto e formidabil nume" ("Mighty spirit and powerful divinity"), by which he attempts to persuade Caronte to allow him to enter Hades.

"[76] The first recording of L'Orfeo was issued in 1939, a freely adapted version of Monteverdi's music by Giacomo Benvenuti,[77] given by the orchestra of La Scala Milan conducted by Ferrucio Calusio.

Most of the editions that followed d'Indy up to the time of the Second World War were arrangements, usually heavily truncated, that provided a basis for performances in the modern opera idiom.