LGBTQ rights in Croatia

In 2024, the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA) ranked Croatia seventeeth in terms of LGBT rights out of 49 observed European countries, which represented an improvement compared to the previous year's position of eighteenth place.

[7] The Adriatic Republic of Ragusa introduced the death penalty for sodomy in 1474 as a response to stereotypical fears that Ottoman conquests in the region will lead to the spread of homosexuality.

[12][13] During the period when Croatia was part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, male homosexual acts were made illegal and punishable with up to two years of prison under the Penal Code of 9 March 1951.

The situation stagnated until 2000 when a new government coalition, consisting mainly of parties of the centre-left and led by Ivica Račan, took power from the HDZ after their ten-year rule.

[20] The 2000s proved a turning point for LGBT history in Croatia with the formation of several LGBT associations (with the Rijeka-based Lesbian organisation Rijeka - LORI in 2000 and ISKORAK in 2002 being among the first); the introduction of unregistered cohabitations; the outlawing of all anti-LGBT discrimination (including recognition of hate-crime based on sexual orientation and gender identity); and the first gay pride event in Zagreb in 2002 during which a group of extremists attacked a number of marchers.

[21] Several political parties as well as both national presidents elected in 2000s have shown public support for LGBT rights, with some politicians even actively participating in Gay Pride events on a regular basis.

[22] Lucija Čikeš MP, a member of the then-ruling HDZ, called for the proposal to be dropped because "the whole universe is heterosexual, from the atom and the smallest particle; from a fly to an elephant".

However, the medical and physical professions, and the media more generally rejected these statements in opposition, warning that all the members of the Sabor had a duty to vote according to the Constitution which bans discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation.

[23] As HDZ is a self-declared Christian democratic party, the then Minister of Health and Social Welfare, Darko Milinović, indicated that the government took the Church's position on the matter seriously.

A number of HNS MPs who are also members of the ruling coalition wanted lesbian couples to be included in the legal change as well, and expressed disappointment that their amendment was not ultimately accepted.

[37][38] In July 2012, the Municipal Court in Varaždin dealt with a case of discrimination and harassment on the grounds of sexual orientation against a professor at the Faculty of Organization and Informatics at the University of Zagreb.

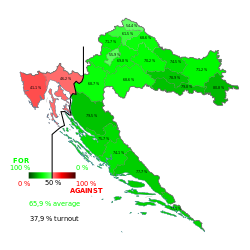

[39] A lobby group established in 2013, "In the Name of the Family", led the call to change the Croatian national constitution so that marriage can only be defined as a union between a man and a woman.

"[21] On 1 March 2013, the Minister for Science, Education and Sports, Željko Jovanović, announced that his ministry would begin an action to remove all homophobic content from books used in both elementary and high schools.

[55][56] In September 2020 gay couple Mladen Kožić and Ivo Šegota became the first same-sex foster parents in history of Croatia, after a three-year long legal battle.

Afterwards, Mladen Kožić and Ivo Šegota, a gay couple aspiring to become foster parents, wrote an open letter to the government saying that by "refusing to include life partners' families in the law ... you further boosted stigma and gave it a legal framework.

The written ruling has not yet arrived, but as stated during the announcement, the court accepted our argument in the lawsuit, based on Croatian regulations and the European Convention on Human Rights.

The Constitutional Court did not repeal the challenged legal provisions, arguing that this would create a legal loophole, but stated unequivocally that the exclusion of same-sex couples from foster care was discriminatory and unconstitutional, and provided clear instructions to the courts, social welfare centers, and other decision-making bodies regarding these issues and indicated they must not exclude applicants based on their life partnership status.

Under the new rules, the undertaking of sex reassignment surgery no longer has to be stated on an individual's birth certificate, thus ensuring that such information remains private.

[62] LGBTQ associations Zagreb Pride, Iskorak and Kontra have been cooperating with the police since 2006 when Croatia first recognized hate crimes based on sexual orientation.

In April of the same year the Minister of the Interior, Ranko Ostojić, together with officials from his ministry launched a national campaign alongside Iskorak and Kontra to encourage LGBT persons to report hate crimes.

[88] The regulations that govern the Croatian institute for transfusions (Hrvatski zavod za transfuzijsku medicinu) in practice restrict gay and bi men's ability to donate blood indefinitely.

[90] A 2007 bylaw on blood products includes among the criteria for a permanent rejection of allogeneic dose providers the generic category of "people whose sexual behavior puts them at a high risk of getting blood-borne infectious diseases",[91] and in turn the institute's blood donation restrictions on men who have sex with men, as of 2021[update], are categorized under "behaviors or activities that expose them to risk of contracting blood-borne infectious diseases".

Ministry of Defence has no internal rules regarding LGB persons, but it follows regulation at the state level which explicitly prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.

The deputy head of Zagreb City Office for General Administration Dragica Kovačić claimed no cases of registrars wishing to be exempted is known.

[147] Other supporters of LGBT rights in Croatia are Rade Šerbedžija, Igor Zidić, Slavenka Drakulić, Vinko Brešan, Severina Vučković, Nataša Janjić, Josipa Lisac, Nevena Rendeli, Šime Lučin, Ivo Banac, Furio Radin, Darinko Kosor, Iva Prpić, Đurđa Adlešič, Drago Pilsel, Lidija Bajuk, Mario Kovač, Nina Violić, former Prime Minister Ivica Račan's widow Dijana Pleština, Maja Vučić, Gordana Lukač-Koritnik, pop group E.N.I.

[148] Damir Hršak, a member of the Labour party, who has publicly spoken about his sexual orientation and has been involved in LGBT activism for years, is the first openly gay politician to become an official candidate for the first European Parliament elections in Croatia, held in April 2013.

The party has, nevertheless, enacted several laws that ban discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity as part of the negotiation process prior to the accession of Croatia to the European Union.

[168][169] Contrary to that, the president of HDSSB, Dragan Vulin, expressed his support for equal rights for same-sex couples in everything except adoption during the 2016 parliamentary election campaign.

Cardinal Josip Bozanić encouraged support for the proposed constitutional amendment in a letter read out in all churches where he singled out heterosexual marriage as being the only union capable of biologically producing children, and thus worthy to be recognised.

The most prominent member of the group, Željka Markić, opposed the Life Partnership Act claiming it was same-sex marriage under a different name, and thus a violation of the Constitution.