LGBTQ rights in Estonia

Among the countries which after World War II were controlled by the former Soviet Union, independent Estonia is now considered to be one of the most liberal when it comes to LGBTQ rights.

[11] Same-sex sexual activity between consenting males, which until 1917 had been illegal in the former Russian Empire, was formally legalised in the newly independent Republic of Estonia when the country's parliament approved changes in the criminal code in 1929.

[26] The campaign against the law was led by the Christian conservative foundation For Family and Tradition (Estonian: SA Perekonna ja Traditsiooni Kaitseks).

[27] In February 2017, the Tallinn Administrative Court ordered the Estonian Government to pay monetary damages for failing to adopt the implementing acts.

[34] Changes made to the Family Law Act in July 2014 permitted them to petition the court to annul such a marriage,[35] but the Ministry had no obligation to do so.

A spokesman for the Ministry said, "during the last five or six years, significant changes have taken place in society, as a result of which it can no longer be said that the marriage of a same-sex couple is contrary to Estonian public order.

A lesbian couple, Leore and Katarina, were the first ones to be officially married on 2 January, the first work day for the Tallinn Vital Statistics Department after the New Year.

[50][51] As an obligation for acceptance into the European Union, Estonia transposed an EU directive into its own laws banning discrimination based on sexual orientation in employment from 1 May 2004.

The Equal Treatment Act (Estonian: Võrdse kohtlemise seadus), which entered into force on 1 January 2009, also prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in employment, but not in the provision of goods and services.

[60] In June 2023, the government of Estonia approved a draft bill to explicitly ban hate speech based on both sexual orientation and gender identity.

[62] According to the Estonian Human Rights Centre, incitement to hatred is already prohibited by paragraph 151 of the Penal Code, but using it in court is extraordinarily difficult due to the current wording.

[11] A journalist writing for the newspaper Postimees in 1929 is confused on the point whether Oinatski is rather a young man in a dress trying to avoid compulsory military service, or a strange woman with entirely feminine speech and expression.

[64][65][66] Gender reassignment was in essence already possible during the Soviet occupation, under ad-hoc regulation set out by the Ministry of Health of the USSR, after the adoption of the ICD-9 in 1980.

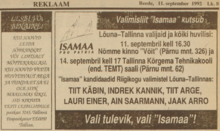

[18] On 6 April 1992, Kristel Regina became the first trans person in independent Estonia to legally correct her name and gender on her birth certificate.

[72] According to her, she first became aware of the possibility of gender reassignment after coming across an article in an East German magazine talking about April Ashley, in 1978.

[18][74] Legal gender recognition is currently regulated by regulation concerning the Common Requirements for Medical Operations for Gender Reassignment (Estonian: Soovahetuse arstlike toimingute ühtsed nõuded), in force since May 1999, and parts of the Vital Statistics Registration Act (Estonian: Perekonnaseisutoimingute seadus) which entered into force in January 2014.

[74][75] To begin the process of gender reassignment, a transgender person must submit an application to the Ministry of Social Affairs for the first appointment with the medical expert committee formed for this purpose.

Afterwards, the decision of the committee together with a written application must be submitted to a county town local government (Estonian: maakonnakeskuse kohalik omavalitsus).

Same-sex attraction tendencies are "generally not an obstacle to military service," according to the head of the vocational department at the Defense Resources Agency (Estonian: Kaitseressursside Amet), Merle Ulst.

[94] Most recently, a queer community bar, Hungr, was opened in April 2023, in Tallinn, aiming to provide a modern, inclusive, and safe space for LGBTQ people and their friends.

While it also had the political ambition of trying to change the attitude of society towards sexual minorities, the main focus was on organizing the fledgling community through various events.

Key speakers at the event included Riho Rahuoja, the Deputy Secretary General for Social Policy at the Ministry of Social Affairs; Christian Veske, the Chief Specialist in the Ministry's Gender Equality Department; Kari Käsper, Project Manager of the "Diversity Enriches" campaign from the Estonian Human Rights Centre; Hanna Kannelmäe from the Estonian Gay Youth NGO; U.S.

[105] In February 2019, the LGBTQ association SevenBow, organizers of the Festheart LGBTI film festival, sued the Rakvere City Council for cutting their funding by 80%.

The court added that the council had also not raised an appropriate legal basis which would have allowed it to deviate from the decision drawn up by the Cultural Affairs Committee.

[107] On 11 June 2023, during a small speaking event organized by an association of gay Christians at the X-Baar, a visiting Finnish pastor and others were violently assaulted by a 25-year-old Estonian-speaking Russian citizen in a homophobic hate crime.

[108][109] The man yelled about God's wrath against homosexuals in Russian, punching the pastor in the face and stabbing a woman sitting next to him with a knife.

He added that words have consequences when politicians or religious leaders "systematically belittle the rights and freedoms of a minority in their public speeches, sooner or later such thoughtless or, on the contrary, very well-thought-out opposing language can become a crime at the hands of some radicalized fanatics.

"[112] On 14 July 2023, a Russian-speaking man who murdered a Jamaican trans woman whom he had met in a Tallinn Old Town bar in 2022 was sentenced to 12 years in jail.

[118] The 2015 Eurobarometer survey showed that 44% of Estonians supported gay, lesbian and bisexual people having the same equal rights as heterosexuals, while 45% were opposed.

[128] The 2023 Eurobarometer found that 41% of Estonians thought same-sex marriage should be allowed throughout Europe, and 51% agreed that "there is nothing wrong in a sexual relationship between two persons of the same sex".