Labor trafficking in the United States

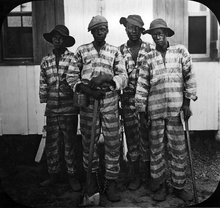

[1] The arrival of the Europeans ushered in the Atlantic slave trade, where Africans were sold into chattel slavery into the American continent.

It lasted from the 15th through 19th centuries and was the largest legal form of human trafficking in the history of the United States, reaching 4 million slaves at its height.

At the beginning of the 19th century, there was growing concern over "white slavery", which referred to the kidnapping of females to work in the sex industry.

A number of laws, such as the Mann Act, were passed to protect white females, and eventually extended to children and women of all races and to a lesser degree men.

[6] According to the National Human Rights Center in Berkeley, California, there are currently about 10,000 forced laborers in the U.S., around one-third of whom are domestic servants and some portion of whom are children.

Research at San Diego State University estimates that there are 2.4 million victims of human trafficking among illegal Mexican immigrants.

[9] In the agriculture sector, the most common victims of trafficking are U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents, undocumented immigrants, and foreign nationals with temporary H-2A visas.

After California Rural Legal Assistance was unable to locate JB Farm Labor contractor, they sued the grower who was ordered to pay the workers back-pay.

[13] In November 2002, Ramiro Ramos, his brother Juan, and their cousin Jose Luis, sub-contractors of a farm in Immokalee, Florida, were charged ten to twelve years each for holding migrant workers in involuntary servitude.

[17] Though the fish are delivered to ports on Honolulu and San Francisco, crew members are not allowed to leave the vessels for years at a time, and have their passports held by boat owners.

The fish are sold on to restaurants, hotels, and stores like Sam's Club and Costco; Whole Foods Market suspended purchases after the AP report.

[20] In January 2018, one boat owner settled a human trafficking lawsuit brought by two escaped fishermen, but the practice largely continues.

[21] The garment industry is particularly susceptible to labor trafficking in part because of a highly immigrant work force, low profit margins, and a tiered production system.

Coupled with a worker population that is vulnerable because of their visa status and unfamiliarity with American laws, this creates a system that is ripe for human trafficking.

[27][28][29][30][31] Domestic servitude is the forced employment of someone as a maid or nanny, and victims are often migrant women who come from low-wage communities in their home countries.

[32] The Associated Press reports, based on interviews in California and Egypt, that trafficking of children for domestic labor in the U.S. includes an extension of an illegal but common practice in Africa.

Families in remote villages send their daughters to work in cities for extra money and the opportunity to escape a dead-end life.

While legally employed domestic house workers are fairly compensated for their work in accordance with national wage laws, domestic servants are typically forced to work extremely long hours for little to no monetary compensation, and psychological and physical means are employed to limit their mobility and freedom.

[32] According to the Department of Health and Human Services, instances of trafficking of adults and children in traveling sales crews, peddling and begging rings are rising.

[6] In one highly publicized case, a group of deaf Mexicans were kidnapped and brought to New York City to sell key chains and miniature screwdriver kits in the subways, at airports, on roadsides.

The traveling nature makes it easier for traffickers to control their victims' sleeping arrangements and food and to alienate them from outside contact.

As independent contractors, they are not overseen by several laws meant to prevent abuse, such as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

[41] Wisconsin governor James E. Doyle said the intent of the law is to "stop companies from putting workers in dangerous and unfair conditions".

[43] Southwestern Advantage lobbied against the bill, arguing that their independent contractor business model nurtured the entrepreneurial spirit.