Lambeth Conference

[3] The idea of these meetings was first suggested in a letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury by Bishop John Henry Hopkins of the Episcopal Diocese of Vermont in 1851.

In 1865 the synod of that province, in an urgent letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury, (Charles Thomas Longley), represented the unsettlement of members of the Canadian church caused by recent legal decisions of the Privy Council and their alarm lest the revived action of convocation "should leave us governed by canons different from those in force in England and Ireland, and thus cause us to drift into the status of an independent branch of the Catholic Church".

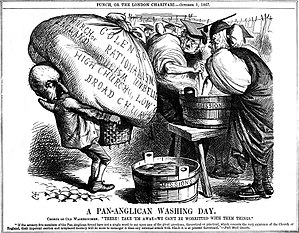

After consulting both houses of the Convocation of Canterbury, Archbishop Longley assented and convened all the bishops of the Anglican Communion (then 144 in number) to meet at Lambeth in 1867.

"[citation needed] Seventy-six bishops accepted the primate's invitation to the first conference, which met at Lambeth on 24 September 1867 and sat for four days, the sessions being in private.

[9] From 1978 onwards the conference has been held on the Canterbury campus of the University of Kent allowing the bishops to live and worship together on the same site for the first time.

The Archbishop of York and several other English bishops refused to attend because they thought such a conference would cause "increased confusion" about controversial issues.

[11] The conference began with a celebration of the Holy Communion at which Henry John Whitehouse, the second Bishop of Illinois, preached; Wilberforce of Oxford later described the sermon as "wordy but not devoid of a certain impressiveness".

Day three was given over[citation needed] to discussing the situation in the Diocese of Natal and its controversial bishop John William Colenso "who had been deposed and excommunicated for heresy because of his unorthodox views of the Old Testament.

"[10] Longley refused to accept a condemnatory resolution proposed by Hopkins, Presiding Bishop of the Americans, but they later voted to note 'the hurt done to the whole communion by the state of the church in Natal'.

Other resolutions have to do with the creation of new sees and missionary jurisdictions, Commendatory Letters, and a voluntary spiritual tribunal in cases of doctrine and the due subordination of synods.

On the final day, the bishops attended Holy Communion at Lambeth Parish Church at which Longley presided; Fulford of Montreal, one of the instigators of the original request, preached.

The agenda of this conference was noticeable for its attention to matters beyond the internal organisation of the Anglican Communion and its attempts to engage with some of the major social issues that the member churches were encountering.

In addition to the encyclical letter, nineteen resolutions were put forth, and the reports of twelve special committees are appended upon which they are based, the subjects being intemperance, purity, divorce, polygamy, observance of Sunday, socialism, care of emigrants, mutual relations of dioceses of the Anglican Communion, home reunion, Scandinavian churches, Old Catholics, etc., Eastern Churches, standards of doctrine and worship.

The Quadrilateral laid down a fourfold basis for home reunion: that agreement should be sought concerning the Holy Scriptures, the Apostles' and Nicene creeds, the two sacraments ordained by Christ himself and the historic episcopate.

The encyclical letter is accompanied by sixty-three resolutions (which include careful provision for provincial organisation and the extension of the title archbishop "to all metropolitans, a thankful recognition of the revival of brotherhoods and sisterhoods, and of the office of deaconess," and a desire to promote friendly relations with the Eastern Churches and the various Old Catholic bodies), and the reports of the eleven committees are subjoined.

The results of the deliberations were embodied in seventy-eight resolutions, which were appended to the encyclical issued, in the name of the conference, by the Archbishop of Canterbury on 8 August.

The document repeated a slightly modified version of the Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral and then called on other Christians to accept it as a basis on which to discuss how they may move toward reunion.

The conference's uncompromising and unqualified rejection of all forms of artificial contraception, even within marriage, was contained in Resolution 68, which said, in part: We utter an emphatic warning against the use of unnatural means for the avoidance of conception, together with the grave dangers – physical, moral and religious – thereby incurred, and against the evils with which the extension of such use threatens the race.

In opposition to the teaching which, under the name of science and religion, encourages married people in the deliberate cultivation of sexual union as an end in itself, we steadfastly uphold what must always be regarded as the governing considerations of Christian marriage.

One is the primary purpose for which marriage exists, namely the continuation of the race through the gift and heritage of children; the other is the paramount importance in married life of deliberate and thoughtful self-control.

[33] The conference dealt with the question of the inter-relations of Anglican international bodies and issues such as marriage and family, human rights, poverty and debt, environment, militarism, justice and peace.

"[41] A controversial incident occurred during the conference when Bishop Emmanuel Chukwuma of Enugu, Nigeria, attempted to exorcise the "homosexual demons" from Richard Kirker, a British priest and the general secretary of the Lesbian and Gay Christian Movement, who was passing out leaflets.

"[42] Reflecting on resolution 1.10 in the lead up to Lambeth 2022, Angela Tilby recalled the intervention of Bishop Michael Bourke, who successfully proposed an amendment which said: "We commit ourselves to listen to the experience of homosexual persons".

[43] Tilby considered that while the amendment had appeared inconsequential at the time, it had indeed been significant: she said that the idea of "patient listening" underpinned the Church of England's process Living in Love and Faith.

In March 2006 the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, issued a pastoral letter[45] to the 38 primates of the Anglican Communion and moderators of the united churches setting out his thinking for the next Lambeth Conference.

Williams indicated that the traditional plenary sessions and resolutions would be reduced and that "We shall be looking at a bigger number of more focused groups, some of which may bring bishops and spouses together."

Robinson was the first Anglican bishop to exercise the office while in an acknowledged same-sex relationship, and Rowan Williams said it was "proving extremely difficult to see under what heading he might be invited to be around", drawing criticism.

In addition, Peter Jensen, Archbishop of Sydney, Australia and Michael Nazir-Ali, Bishop of Rochester, among others announced their intentions not to attend.

[49] GAFCON involved Martyn Minns, Peter Akinola and other dissenters[50] who considered themselves to be in a state of impaired communion with the American Episcopal Church and the See of Canterbury.

[64] This prompted criticism from several LGBTQ+ activists including Jayne Ozanne and Sandi Toksvig,[64][65][66] and the signing by 175 bishops and primates of a pro-LGBTQ statement asserting the holiness of the love of all committed same-sex couples.