Land-grant university

The Morrill Act of 1862 provided land in the western parts of North America that states sold to fund new or existing colleges and universities.

[3][4] This mission was in contrast to the historic practice of existing colleges which offered a narrow Classical curriculum based heavily on Latin, Greek and mathematics.

[5] The Morrill Act quickly stimulated the creation of new state colleges and the expansion of existing institutions to include these new mandates.

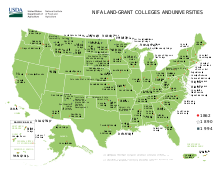

[6][7] Ultimately, most land-grant schools became large state universities that offer a full spectrum of educational and research opportunities.

[8] The concept of federal support for agricultural and technical educational institutions in every state first rose to national attention through the efforts of Jonathan Baldwin Turner of Illinois in the late 1840s.

This act required each state to show that race was not an admissions criterion, or else to designate a separate land-grant institution for persons of color.

The land-grant college system has been seen as a major contributor in the faster growth rate of the U.S. economy that led to its overtaking the United Kingdom as economic superpower, according to research by faculty from the State University of New York.

What originally was described as "teaching, research, and service" was renamed "learning, discovery, and engagement" by the Kellogg Commission on the Future of State and Land-Grant Universities.

[22] Historians once presented a "Romantic" interpretation of the origins as a product of a working class democratic demand for access to higher education.

The outreach mission was further expanded by the Smith–Lever Act of 1914 to include cooperative extension—the sending of agents into rural areas to help bring the results of agricultural research to the end users.

In a 1972 Special Education Amendment, American Samoa, Guam, Micronesia, Northern Marianas, and the Virgin Islands each received $3 million.

[29][30] For example, the University of Illinois System states, These lands were the traditional birthright of indigenous peoples who were forcibly removed and who have faced two centuries of struggle for survival and identity in the wake of dispossession.

We hereby acknowledge the ground on which we stand so that all who come here know that we recognize our responsibilities to the peoples of that land and that we strive to address that history so that it guides our work in the present and the future.

They pointed out that land grants were used not only for campus sites but also included many other parcels that universities rented or sold to generate funds that formed the basis of their endowments.

[13] Lee and Ahtone also pointed out that only a few land-grant universities have undertaken significant efforts at reconciliation with respect to the latter types of parcels.