Langalibalele

Langalibalele (isiHlubi: meaning 'The blazing sun', also known as Mthethwa, Mdingi (c 1814 – 1889), was king of the amaHlubi, a Bantu tribe in what is the modern-day province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

In 1879 the colonial authorities of Natal demanded that the guns be registered; Langalibalele refused and a stand-off ensued, resulting in a violent skirmish in which British troops were brutally killed.

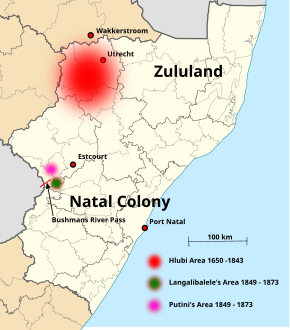

[2] The amaHlubi, a Bantu tribe speaking a Tekela dialect, had settled in the northern part of the province between the Buffalo and Blood Rivers.

[3] During the first decade of the nineteenth century the AbaThethwa King Dingiswayo, a neighbour of the AmaHlubi, set about consolidating the various Nguni people under his leadership.

In 1818 he was killed in battle and after a civil war, power passed into the hands of one of his lieutenants, Shaka, King of the Zulu clan.

[4] At the time of King Langalibalele I's birth, European settlements in Southern Africa were confined to the British controlled Cape Colony[5] and to the Portuguese fortress of Lourenço Marques.

[10] From 1856 until 1877, the post of diplomatic agent was held by Sir Theophilus Shepstone, son of a missionary and who had been brought up at the mission station.

[citation needed] Prince Duba asked King Langalibalele I to accompany him to his mother's place at the AmaJuba Clan mountains.

Gxiva managed to release King Langalibalele I who escaped during the night and crossed the Mzinyathi river which was in flood.

[14] The discovery of diamonds in Kimberley, in the British Colony of Griqualand West, attracted thousand of workers, black and white.

Many young men from the amaHlubi became labourers on the mines and some were paid in guns rather than in money, a practice that was legal in Griqualand West.

[16] In the event, Sir Benjamin Pine, who arrived in the Colony as lieutenant governor in July 1873 ordered the arrest of Langalibalele.

Alison and Barter were to travel under cover of darkness and to meet up at the top of the Bushmans River Pass on Monday 3 November 1873 at 0600 hrs and block Langalibalele's flight.

[18][19] On 11 November martial law was declared in the Natal colony, and two flying columns, one under Allison, were sent to search for Langalibalele in Basutoland.

They entered the protectorate via the Orange Free State and on 11 December reached a spot in the Maluti Mountains that bore evidence of Langalibalele having recently been there.

[22][23] Almost immediately after Langalibalele arrived at Robben island, information began to surface across southern Africa about the unfair nature of the Chief's treatment.

He also explained that his personal interest in the case was the protection that he had received from Langalibilele's namesake during the latter stages of his journey to Lourenco Marques.

The Cape government Minister and spokesman John X. Merriman publicly condemned the trial ("Natal Prisoner's Bill") and demanded that it be considered illegitimate.

Firstly, they insisted that no white man would have been sentenced so severely, that the Natal court had therefore been guilty of racial prejudice, and that Langalibalele "had been victimised because of his colour".

Secondly, they argued that, as a locally elected government, they neither fell under Natal's jurisdiction, nor were obliged to follow British imperial requests in this regard.

[28] In keeping with the amaHlubi tradition, his burial place was kept secret until in October 1950 his grandson revealed the site to the Native Commissioner in Estcourt.

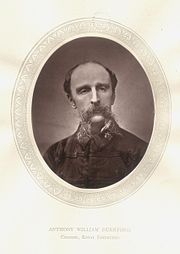

To a lesser extent Durnford's views that were similar to Colenso's, and although he had held his nerve during the confrontation with the amaHlubi at the top of the Bushmans River Pass, he was ostracised from local society.

One of the underlying causes of the Langalibalele "rebellion" was an inconsistent policy in the various British colonies towards the native populations and in particular the ownership of guns.

While his proposed native policy was too liberal for the Boer republics, it was considered too harsh by the Cape's government, which also rejected the way in which it was to be forcibly imposed on southern Africa from outside.