Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector

[3][4][5][6] The hydrogen atom is a Kepler problem, since it comprises two charged particles interacting by Coulomb's law of electrostatics, another inverse-square central force.

The LRL vector was essential in the first quantum mechanical derivation of the spectrum of the hydrogen atom,[7][8] before the development of the Schrödinger equation.

[2][14][16] Various generalizations of the LRL vector have been defined, which incorporate the effects of special relativity, electromagnetic fields and even different types of central forces.

can be defined for all central forces, but this generalized vector is a complicated function of position, and usually not expressible in closed form.

[15] Jakob Hermann was the first to show that A is conserved for a special case of the inverse-square central force,[22] and worked out its connection to the eccentricity of the orbital ellipse.

[23] At the end of the century, Pierre-Simon de Laplace rediscovered the conservation of A, deriving it analytically, rather than geometrically.

[25] Gibbs' derivation was used as an example by Carl Runge in a popular German textbook on vectors,[26] which was referenced by Wilhelm Lenz in his paper on the (old) quantum mechanical treatment of the hydrogen atom.

This definition of the LRL vector A pertains to a single point particle of mass m moving under the action of a fixed force.

[33] Nevertheless, equivalently, they are also quantized in the Nambu framework, such as this classical Kepler problem into the quantum hydrogen atom.

The perturbation potential h(r) may be any sort of function, but should be significantly weaker than the main inverse-square force between the two bodies.

This approach was used to help verify Einstein's theory of general relativity, which adds a small effective inverse-cubic perturbation to the normal Newtonian gravitational potential,[35]

to express r in terms of θ, the precession rate of the periapsis caused by this non-Newtonian perturbation is calculated to be[35]

where i=1,2,3 and εijs is the fully antisymmetric tensor, i.e., the Levi-Civita symbol; the summation index s is used here to avoid confusion with the force parameter k defined above.

Importantly, by dint of the vanishing of C2, they are independent of the ℓ and m quantum numbers, making the energy levels degenerate.

The additional symmetry operators A have connected the different ℓ multiplets among themselves, for a given energy (and C1), dictating n2 states at each level.

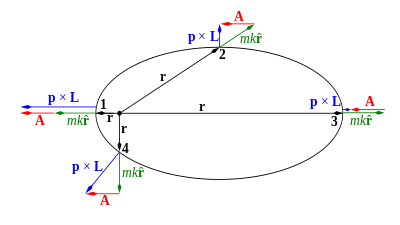

[51] Classically, the higher symmetry of the Kepler problem allows for continuous alterations of the orbits that preserve energy but not angular momentum; expressed another way, orbits of the same energy but different angular momentum (eccentricity) can be transformed continuously into one another.

For negative energies – i.e., for bound systems – the higher symmetry group is SO(4), which preserves the length of four-dimensional vectors

[10] Specifically, Fock showed that the Schrödinger wavefunction in the momentum space for the Kepler problem was the stereographic projection of the spherical harmonics on the sphere.

Rotation of the sphere and re-projection results in a continuous mapping of the elliptical orbits without changing the energy, an SO(4) symmetry sometimes known as Fock symmetry;[52] quantum mechanically, this corresponds to a mixing of all orbitals of the same energy quantum number n. Valentine Bargmann noted subsequently that the Poisson brackets for the angular momentum vector L and the scaled LRL vector A formed the Lie algebra for SO(4).

[11][42] Simply put, the six quantities A and L correspond to the six conserved angular momenta in four dimensions, associated with the six possible simple rotations in that space (there are six ways of choosing two axes from four).

For positive energies – i.e., for unbound, "scattered" systems – the higher symmetry group is SO(3,1), which preserves the Minkowski length of 4-vectors

Both the negative- and positive-energy cases were considered by Fock[10] and Bargmann[11] and have been reviewed encyclopedically by Bander and Itzykson.

An elegant action-angle variables solution for the Kepler problem can be obtained by eliminating the redundant four-dimensional coordinates

The following are arguments showing that the LRL vector is conserved under central forces that obey an inverse-square law.

Subtraction and re-expression in terms of the Cartesian momenta px and py shows that Γ is equivalent to the LRL vector

The connection between the rotational symmetry described above and the conservation of the LRL vector can be made quantitative by way of Noether's theorem.

This theorem, which is used for finding constants of motion, states that any infinitesimal variation of the generalized coordinates of a physical system

where i equals 1, 2 and 3, with xi and pi being the i-th components of the position and momentum vectors r and p, respectively; as usual, δis represents the Kronecker delta.

Noether's theorem derivation of the conservation of the LRL vector A is elegant, but has one drawback: the coordinate variation δxi involves not only the position r, but also the momentum p or, equivalently, the velocity v.[62] This drawback may be eliminated by instead deriving the conservation of A using an approach pioneered by Sophus Lie.

[63][64] Specifically, one may define a Lie transformation[51] in which the coordinates r and the time t are scaled by different powers of a parameter λ (Figure 9),