Laser cutting

While typically used for industrial manufacturing applications, it is now used by schools, small businesses, architecture, and hobbyists.

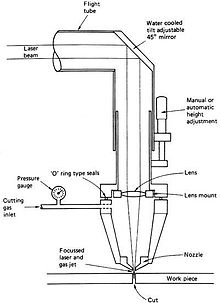

The focused laser beam is directed at the material, which then either melts, burns, vaporizes away, or is blown away by a jet of gas,[1] leaving an edge with a high-quality surface finish.

[2] In 1965, the first production laser cutting machine was used to drill holes in diamond dies.

Piercing usually involves a high-power pulsed laser beam which slowly makes a hole in the material, taking around 5–15 seconds for 0.5-inch-thick (13 mm) stainless steel, for example.

The parallel rays of coherent light from the laser source often fall in the range between 0.06–0.08 inches (1.5–2.0 mm) in diameter.

There is also a reduced chance of warping the material that is being cut, as laser systems have a small heat-affected zone.

[13] CO2 lasers are commonly "pumped" by passing a current through the gas mix (DC-excited) or using radio frequency energy (RF-excited).

In a fast axial flow resonator, the mixture of carbon dioxide, helium, and nitrogen is circulated at high velocity by a turbine or blower.

Transverse flow lasers circulate the gas mix at a lower velocity, requiring a simpler blower.

The laser generator and external optics (including the focus lens) require cooling.

Depending on system size and configuration, waste heat may be transferred by a coolant or directly to air.

Unlike CO2, Fiber technology utilizes a solid gain medium, as opposed to a gas or liquid.

With a wavelength of only 1064 nanometers fiber lasers produce an extremely small spot size (up to 100 times smaller compared to the CO2) making it ideal for cutting reflective metal material.

In vaporization cutting, the focused beam heats the surface of the material to a flashpoint and generates a keyhole.

Nonmelting materials such as wood, carbon, and thermoset plastics are usually cut by this method.

The separation of microelectronic chips as prepared in semiconductor device fabrication from silicon wafers may be performed by the so-called stealth dicing process, which operates with a pulsed Nd:YAG laser, the wavelength of which (1064 nm) is well adapted to the electronic band gap of silicon (1.11 eV or 1117 nm).

[citation needed] Standard roughness Rz increases with the sheet thickness, but decreases with laser power and cutting speed.

[13] There are generally three different configurations of industrial laser cutting machines: moving material, hybrid, and flying optics systems.

This method provides a constant distance from the laser generator to the workpiece and a single point from which to remove cutting effluent.

This can result in reduced power loss in the delivery system and more capacity per watt than flying optics machines.

Flying optics cutters keep the workpiece stationary during processing and often do not require material clamping.

Flying optics machines are the fastest type, which is advantageous when cutting thinner workpieces.

Common methods for controlling this include collimation, adaptive optics, or the use of a constant beam length axis.

In addition, there are various methods of orienting the laser beam to a shaped workpiece, maintaining a proper focus distance and nozzle standoff.

Essentially, the first pulse removes material from the surface and the second prevents the ejecta from adhering to the side of the hole or cut.

Common industrial systems (≥1 kW) will cut carbon steel metal from 0.51 – 13 mm in thickness.