Late Shang

Shang ritual focussed on offerings to ancestors, enabling modern investigators to deduce a king list that largely matches that of the traditional histories of Sima Qian and the Bamboo Annals.

The Late Shang shared many features of the earlier Erlitou and Erligang cultures, including the rammed earth technique for foundations of rectangular walled compounds.

[11] The city covered an area of some 25 km2 (9.7 sq mi), focussed on a complex of palaces and temples on a rise surrounded by the Huan River on its north and east, and with an artificial pond on its western side.

[15][16] More workshops, handling bronze, pottery, jade and bone, were concentrated in at least three production zones: south of the palace district, east of it across the river, and in the west of the city.

[23][24] The Tomb of Fu Hao yielded some 1,600 kg (3,500 lb) of bronze vessels, weapons and tools, as well as hundreds of jades and other worked stones, bone carvings and pottery.

[32] It was succeeded in the middle part of the millennium by the Erligang culture, centred on a large walled city at Zhengzhou and expanding across an area stretching as far south as the Yangtze River.

[42][43][44] The most prominent innovations of the Late Shang – writing, horse-drawn chariots, massive tombs and human sacrifice on an unprecedented scale – all appeared at about the same time, in the reign of king Wu Ding.

Most scholars assume that it continued uninterrupted through the succeeding Western Zhou period up to a solar eclipse recorded in 720 BC, which provides a secure correspondence with Julian days.

[88] The prefix used depended on the relationship to the current king, with near predecessors denoted by kinship terms such as 兄 Xiōng (elder brother) or 父 Fù (father).

In contrast, the standardized ritual schedule and recording of cycle counts in period V permits estimates of the lengths of the last two reigns, though these have ranged between 20 and 33 years.

[144] The core area of the Late Shang state lay in the eastern foothills of the Taihang Mountains, stretching from around 200 km (120 mi) north of Anyang to a similar distance to the south.

[146][1] In the immediate surroundings of the capital, the Huan River valley experienced a substantial increase in population and growth of regional centres during the Huanbei and Late Shang periods.

[162] Royal forays were more limited, with the exception of Di Xin's campaign against the Rénfāng 人方 in the Huai River valley to the southeast, which may have lasted at least seven months.

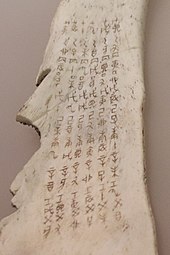

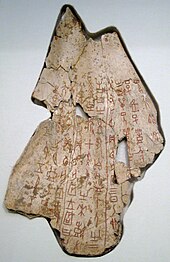

[190][191] The main source of information about Shang religious belief and practice is the oracle bones, supplemented by archaeological finds of ritual vessels and sacrifices.

[202] Another group, called the "High Ancestors" in the inscriptions and the "Former Lords" in modern scholarship, includes figures such as Kuí 夔 (or Náo 夒) and Wáng-hài 王亥, a name that occurs in some texts from the Warring States period.

It was unlucky, a girl.Based on an interpretation of certain characters in the oracle bone script, Kwang-chih Chang proposed that Shang kings interceded with the spirit world as shamans.

[234][236] Across the Huan River lies the Xibeigang cemetery, with eight large tombs each consisting of a square shaft some 12 m (39 ft) deep approached by four ramps dug into the earth and approximately aligned with the cardinal directions.

[248] This medium-sized tomb, with 16 human victims and a dog, also contained 1,600 kg (3,500 lb) of bronze, 755 jades, 110 pieces of worked stone, 564 objects of carved bone, two ivory cups inlaid with turquoise, 6,880 cowrie shells and 11 pots.

[255] A cache of oracle bones found at the Huayuanzhang East site, southeast of the palace-temple area, contains divinations performed on behalf of one of these princes during the reign of Wu Ding.

[258] The term fù (婦 'lady') is not completely understood, but is generally thought to denote women of high status, including the king's consorts and those of his sons.

The titles hóu 侯, diàn 甸 and (less commonly) bó 伯 were often appended to place names, suggesting local lords affiliated with the Shang.

[272] Scholars such as Guo Moruo and Chen Mengjia proposed that the Shang represented the "slave society" phase prescribed by Marxian historical materialism.

[278] Pottery was produced locally throughout the North China Plain, but specialist crafts were concentrated in the workshops of the capital, drawing on raw materials from the countryside and further afield.

[291] Summers in modern Anyang feature torrential bursts of rainfall, especially in July, triggered when the East Asian Monsoon collides with cold air from the Loess Plateau on the eastern slopes of the Taihang Mountains.

[333] Shang workshops also produced much smaller amounts of luxury white pottery, richly decorated with motifs similar to those found on bronze and other artifacts.

[338] One workshop, in the eastern part of the settlement, has been systematically excavated, with a single trench on the site yielding 34 t (37 short tons) of worked and unworked bones.

[371] King lists were maintained by many early states, not only in China but also in the Middle East and the Americas, as a means of legitimizing the current ruler by tracing a linear succession back the founder.

[374] Archaeological discoveries have revealed a much more complex picture of the Late Shang period, with other regional powers such as Sanxingdui in the Sichuan Basin and the Wucheng culture on the Gan River.

According to the "ancient text" version of the Bamboo Annals, the final move was by Wu Ding's uncle Pan Geng to a place called Yīn (殷).

[389][q] The theory that the dynasty was called Shāng up to Pan Geng's relocation of the capital and Yīn afterwards first appeared in the Diwang shiji by Huangfu Mi (3rd century AD).