Late Spring

[3] These films are characterized by, among other traits, an exclusive focus on stories about families during Japan's immediate postwar era, a tendency towards very simple plots and the use of a generally static camera.

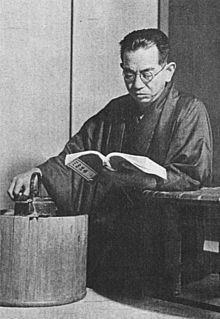

Professor Shukichi Somiya (Chishu Ryu), a widower, has only one child, a twenty-seven-year-old unmarried daughter, Noriko (Setsuko Hara), who takes care of the household and the everyday needs—cooking, cleaning, mending, etc.—of her father.

While packing their luggage for the trip home, Noriko asks her father why they cannot simply stay as they are now, even if he does remarry – she cannot imagine herself any happier than living with and taking care of him.

[10] The censors at first automatically deleted a reference in the script to the Hollywood star Gary Cooper, but then reinstated it when they realized that the comparison was to Noriko’s (unseen) suitor Satake, who is described by the female characters as attractive, and was thus flattering to the American actor.

"[14] One scholar, Lars-Martin Sorensen, has claimed that Ozu's partial aim in making the film was to present an ideal of Japan at odds with that which the Occupation wanted to promote, and that he successfully subverted the censorship in order to accomplish this.

"[11] Sorensen also claims that, to Ozu’s audience, "the exaltation of Japanese tradition and cultural and religious heritage must have brought remembrances of the good old days when Japan was still winning her battles abroad and nationalism reached its peak.

[26] Her tall frame and strong facial features—including very large eyes and a prominent nose—were unusual among Japanese actresses at the time; it has been rumored, but not verified, that she has a German grandparent.

"[42] Geist sums up her analysis of several major Ozu films of the postwar period by asserting that "the narratives unfold with an astounding precision in which no shot and certainly no scene is wasted and all is overlayered with an intricate web of interlocking meaning.

[25] However, like Aunt Masa, Shukichi is also associated with the traditions of old Japan, such as the city of Kyoto with its ancient temples and Zen rock gardens, and the Noh play that he so clearly enjoys.

"[52] In A Brother and His Young Sister (Ani to sono imoto, 1939) by Shimazu, for example, "the home is sanctified as a place of warmth and generosity, feelings that were rapidly vanishing in society.

"[55] Yet despite the fact that these home dramas by Ozu "tend to lack social relevance," they "came to occupy the mainstream of the genre and can be considered perfect expressions of 'my home-ism,' whereby one’s family is cherished to the exclusion of everything else.

She alludes to a famous poem by the waka poet of the Heian period, Ariwara no Narihira, in which each of the five lines begins with one syllable that, spoken together, spell out the word for "water iris" ("ka-ki-tsu-ba-ta").

[58][note 4] As Norman Holland explains in an essay on the film, "the iris is associated with late spring, the movie’s title",[18] and the play contains a great deal of sexual and religious symbolism.

[64] Ozu himself, however, in several prewar films, such as I Was Born, But… and Passing Fancy, had undercut, according to Sato, this image of the archetypal strong father by depicting parents who were downtrodden "salarymen" (sarariman, to use the Japanese term), or poor working-class laborers, who sometimes lost the respect of their rebellious children.

Bordwell suggests that his motive was primarily visual, because the angle allowed him to create distinctive compositions within the frame and "make every image sharp, stable and striking.

"[76] Another critic believes that the ultimate purpose of the low camera position was to allow the audience to assume "a viewpoint of reverence" towards the ordinary people in his films, such as Noriko and her father.

")[92] This self-restraint by the filmmaker is now seen as very modern, because although fades, dissolves and even wipes were all part of common cinematic grammar worldwide at the time of Late Spring (and long afterwards), such devices are often considered somewhat "old fashioned" today, when straight cuts are the norm.

Sato (citing the critic Keinosuke Nanbu) compares the shots to the use of the curtain in the Western theatre, that "both present the environment of the next sequence and stimulate the viewer's anticipation.

[98] The most discussed instance of a pillow shot in any Ozu film—indeed, the most famous crux in the director's work[99]—is the scene that takes place at an inn in Kyoto, in which a vase figures prominently.

Then there is a ten-second shot of the same vase, identical to the earlier one, as the music on the soundtrack swells, cuing the next scene (which takes place at the Ryōan-ji rock garden in Kyoto, the following day).

"[108] Those who hold this interpretation argue that this aspect of Ozu's work gives it its universality, and helps it transcend the specifically Japanese cultural context in which the films were created.

"[110] A critical tendency opposing the "life cycle" theory emphasizes the differences in tone and intent between this film and other Ozu works that deal with similar themes, situations and characters.

In the second, Noriko takes advantage of a conversational opening [about marriage] to overturn the entire plot... she accepts a man [as husband] she has known for a long time—a widower with a child.

"[111] In contrast, "what happens [in Late Spring] at deeper levels is angry, passionate and—wrong, we feel, because the father and the daughter are forced to do something neither one of them wants to do, and the result will be resentment and unhappiness.

"[115] The publication Shin Yukan, in its review of September 20, emphasized the scenes that take place in Kyoto, describing them as embodying "the calm Japanese atmosphere" of the entire work.

)[122] Ozu's younger contemporary, Akira Kurosawa, in 1999 published a conversation with his daughter Kazuko in which he provided his unranked personal listing, in chronological order, of the top 100 films, both Japanese and non-Japanese, of all time.

[128] Kurosawa biographer Stuart Galbraith IV, reviewing the Criterion Collection DVD, called the work "archetypal postwar Ozu" and "a masterful distillation of themes its director would return to again and again...

"[151] Because of perceived similarities, in subject matter and in his contemplative approach, to the Japanese master, Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien has been called "an artistic heir to Ozu.

"[155] As in Ozu's classic, the narrative has a wedding which is never shown on screen[155] and Suo consistently imitates the older master's "much posited predilection for carefully composed static shots from a low camera angle... affectionately poking fun at the restrained and easy going 'life goes on' philosophy of its model.

It also includes Tokyo-Ga, an Ozu tribute by director Wim Wenders; an audio commentary by Richard Peña; and essays by Michael Atkinson[163] and Donald Richie.