Latent heat

Black used the term in the context of calorimetry where a heat transfer caused a volume change in a body while its temperature was constant.

The original usage of the term, as introduced by Black, was applied to systems that were intentionally held at constant temperature.

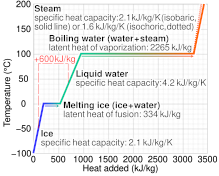

[4] Latent heat is energy released or absorbed by a body or a thermodynamic system during a constant-temperature process.

Latent heat flux has been commonly measured with the Bowen ratio technique, or more recently since the mid-1900s by the eddy covariance method.

In 1748, an account was published in The Edinburgh Physical and Literary Essays of an experiment by the Scottish physician and chemist William Cullen.

In his letter Cooling by Evaporation, Franklin noted that, "One may see the possibility of freezing a man to death on a warm summer's day.

[9][10] The term latent heat was introduced into calorimetry around 1750 by Joseph Black, commissioned by producers of Scotch whisky in search of ideal quantities of fuel and water for their distilling process to study system changes, such as of volume and pressure, when the thermodynamic system was held at constant temperature in a thermal bath.

[5] In 1757, Black started to investigate if heat, therefore, was required for the melting of a solid, independent of any rise in temperature.

By comparing the resulting temperatures, he could conclude that, for instance, the temperature of the sample melted from ice was 140 °F lower than the other sample, thus melting the ice absorbed 140 "degrees of heat" that could not be measured by the thermometer, yet needed to be supplied, thus it was "latent" (hidden).

[15] Black had placed equal masses of ice at 32 °F (0 °C) and water at 33 °F (0.6 °C) respectively in two identical, well separated containers.

A specific latent heat (L) expresses the amount of energy in the form of heat (Q) required to completely effect a phase change of a unit of mass (m), usually 1kg, of a substance as an intensive property: Intensive properties are material characteristics and are not dependent on the size or extent of the sample.

For sublimation and deposition from and into ice, the specific latent heat is almost constant in the temperature range from −40 °C to 0 °C and can be approximated by the following empirical quadratic function: As the temperature (or pressure) rises to the critical point, the latent heat of vaporization falls to zero.