Law school of Berytus

The course of study at Beirut lasted for five years and consisted in the revision and analysis of classical legal texts and imperial constitutions, in addition to case discussions.

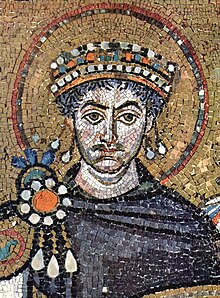

Justinian took a personal interest in the teaching process, charging the bishop of Beirut, the governor of Phoenicia Maritima and the teachers with discipline maintenance in the school.

[1] With legal appeals, petitions from subjects and judicial queries of magistrates and governors, the emperors were careful to consult with the jurists (iuris consulti), who were usually secretaries drafted from the equestrian order.

The edict repositories and the imperially sponsored legal scholarship gave rise to the earliest law school system of the Western world, aimed specifically at training professional jurists.

[1] During the reign of Augustus, Beirut was established under the name Colonia Iulia Augusta Felix Berytus[a][2](and granted the status of Ius Italicum) as a colony for Battle of Actium veterans from the fifth Macedonian and the third Gallic legions.

Edward Gibbon suggested its founding may have been directed by locally born Emperor Alexander Severus, who reigned during AD 222–235;[8] this hypothesis had been supported by Gilles Ménage, a late 17th-century French scholar.

Italian jurist Scipione Gentili, however, attributed the school's foundation to Augustus, while 19th-century German theologian Karl Hase advocated its establishment shortly after the victory at Actium (31 BC).

[11] Theodor Mommsen linked the establishment of the law school in Beirut with the need for jurists, since the city was chosen to serve as a repository for Roman imperial edicts concerning the eastern provinces.

This function was first recorded in 196 AD, the date of the earliest constitutions contained in the Gregorian Codex, but the city is thought to have served as a repository since earlier times.

[14] The 3rd-century emperors Diocletian and Maximian issued constitutions exempting the students of the law school of Beirut from compulsory service in their hometowns.

[17][18][19][20] By the 5th century, Beirut had established its leading position and repute among the Empire's law schools; its teachers were highly regarded and played a chief role in the development of legal learning in the East to the point that they were dubbed “ecumenical masters”.

The lecturer would discuss and analyse legal texts by adding his own comments, which included references to analogous passages from imperial constitutions or from the works of prominent classical Roman jurists such as Ulpian.

[33][34] The courses consisted of lectures and self-study using materials advanced in his Corpus Juris Civilis, namely the Institutiones (Institutes), Digesta (Digest) and Codex (Code).

During this period, a succession of seven highly esteemed law masters was largely responsible for the revival of legal education in the Eastern Roman Empire.

Cyrillus wrote a precise treatise on definitions that supplied the materials for many important scholia appended to the first and second titles of the eleventh book of the Basilika.

Euxenius was the brother of the city's bishop Eustathius and was involved in the 460 religious controversy caused by Timothy Aelurus, which opposed the Miaphysites to the followers of the Council of Chalcedon.

In his 238 AD panegyric to Christian scholar Origen of Alexandria, Cappadocian bishop Gregory Thaumaturgus relates taking extensive Latin and Roman law courses in Beirut.

[60] Gazan lawyer and church historian Sozomen,[61] also a law student at Beirut, wrote in his Historia Ecclesiastica about Triphyllius, a convert to Christendom who became the bishop of Nicosia.

[58] Zacharias Rhetor studied law at Beirut between 487 and 492, then worked as a lawyer in Constantinople until his imperial contacts won him the appointment as bishop of Mytilene.

Among Rhetor's works is the biography of Severus, the last miaphysite patriarch of Antioch and one of the founders of the Syriac Orthodox Church, who had also been a law student in Beirut as of 486.

In the 5th century, Zacharias Rhetor reported that the school stood next to the "Temple of God", the description of which permitted its identification with the Byzantine Anastasis cathedral.

[74][75][76][77] The school garnered accolades throughout its existence and was bestowed with the title Berytus Nutrix Legum (Beirut, Mother of Laws) by Eunapius, Libanius, Zacharias Rhetor and finally by Emperor Justinian.

[52]From the 3rd century, the school tolerated Christian teachings, producing a number of students who would become influential church leaders and bishops, such as Pamphilus of Caesarea, Severus of Antioch and Aphian.

[78][79] Two professors from the law school of Beirut, Dorotheus and Anatolius, had such a repute for their wisdom and knowledge that they were especially praised by Justinian in the opening of his Tanta constitution.

The emperor summoned both professors to assist his minister Tribonian in compiling the Codex of Justinian,[52] the Empire's body of civil laws issued between 529 and 534.

The Tanta passage reads: Dorotheus, an illustrious man, of great eloquence and quæstorian rank, whom, when he was engaged in delivering the law to students in the most brilliant city of Berytus, we, moved by his great reputation and renown, summoned to our presence and made to share in the work in question; again, Anatolius, an illustrious person, a magistrate, who, like the last, was invited to this work when acting as an exponent of law at Berytus, a man who came of an ancient stock, as both his father Leontius and his grandfather Eudoxius left behind them an excellent report in respect of legal learning...[80]For centuries following its compilation, the work of Justinian's commission was studied and incorporated into the legal systems of different nations and has profoundly impacted the Byzantine law and the Western legal tradition.

[81] Peter Stein asserts that the texts of ancient Roman law have constituted "a kind of legal supermarket, in which lawyers of different periods have found what they needed at the time.

It was written in Greek, since Latin had fallen into disuse, and its provisions continued to be applied in later centuries in the neighboring Balkan and Asia Minor regions, with surviving translations in Slavic, Armenian and Arabic.

[83][84][85] Emperor Basil I, who ruled in the 9th century, issued the Prochiron and the Epanagoge, which were legal compilations invalidating parts of the Ecloga and restoring the Justinian laws.