Law of Canada

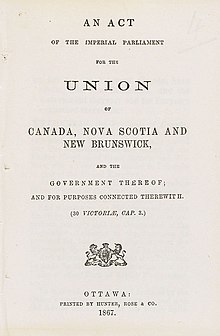

[4][5] The Constitution of Canada is the supreme law of the country, and consists of written text and unwritten conventions.

[9] Canada's judiciary plays an important role in interpreting laws and has the power to strike down Acts of Parliament that violate the constitution.

All judges at the superior and appellate levels are appointed after consultation with non-governmental legal bodies.

The federal Cabinet also appoints justices to superior courts in the provincial and territorial jurisdictions.

[15] Canadian Aboriginal law provides certain constitutionally recognized rights to land and traditional practices for Indigenous groups in Canada.

[16] Various treaties and case laws were established to mediate relations between Europeans and many Indigenous peoples.

[23] However, the Supreme Court of Canada has found that this list is not intended to be exhaustive, and in 1998's Reference re Secession of Quebec identified four "supporting principles and rules" that are included as unwritten elements of the constitution: federalism, democracy, constitutionalism and the rule of law, and respect for minorities.

Matters under federal jurisdiction include criminal law, trade and commerce, banking, and immigration.

[28][30] The Constitution Act, 1867 also provides that, while provinces establish their own superior courts, the federal government appoints their judges.

[32] This last power resulted in the federal Parliament's creation of the Supreme Court of Canada.

Sections 91 and 94A of the Constitution Act, 1867 set out the subject matters for exclusive federal jurisdiction.

Nine of the provinces, other than Quebec, and the federal territories, follow the common law legal tradition.

Equally, courts have power under the provincial Judicature Acts to apply equity.

[44] Decisions from Commonwealth nations, aside from England, are also often treated as persuasive sources of law in Canada.

Cree, Blackfoot, Mi'kmaq and numerous other First Nations; Inuit; and Métis will apply their own legal traditions in daily life, creating contracts, working with governmental and corporate entities, ecological management and criminal proceedings and family law.

[48] The legal precedents set millennia ago are known through stories and derived from the actions and past responses as well as through continuous interpretation by elders and law-keepers—the same process by which nearly all legal traditions, from common laws and civil codes, are formed.

One thing most Indigenous legal and governance traditions have in common is their use of clans such as Anishinaabek's doodeman (though most are matrilineal like Gitx̱san's Wilps).

[59] Individual provinces have codified some principles of contract law in a Sale of Goods Act, which was modeled on early English versions.

[62] Criminal law in Canada falls under the exclusive legislative jurisdiction of the federal government.

The power to enact criminal law is derived from section 91(27) of the Constitution Act, 1867.

Provinces also have laws dealing with marital property and with family maintenance (including spousal support).

Human rights are also protected by federal and provincial statutes, which apply to governments as well as to the private sector.

Human rights laws generally prohibit discrimination on personal characteristics in housing, employment, and services to the public.

The Parliament of Canada has exclusive jurisdiction to regulate matters relating to bankruptcy and insolvency, by virtue of s.91 of the Constitution Act, 1867.

[70] Provincial legislation under the property and civil rights power of the Constitution Act, 1867 regulates the resolution of financial difficulties that occur before the onset of insolvency.

[71] Most labour regulation in Canada is conducted at the provincial level by government agencies and boards.

Through Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, Indigenous nations retain significant rights and title.

It, however, remains unclear the degree to which Indigenous nations have authority over judicial matters.

[77] Especially since 1995, the Government of Canada has maintained a policy of recognizing the inherent right of self-governance under section 35.

[78] The evolution through cases such as Delgamuukw-Gisday'wa and the Tsilhqot'in Nation v British Columbia has affirmed the Euro-Canadian courts' needs to meaningfully engage with Indigenous legal systems, including through Indigenous structures of dispute resolution.