Laws of Cricket

But MCC retains copyright of the Laws and remains the only body that may change them, although usually this is only done after close consultation with the ICC and other interested parties such as the Association of Cricket Umpires and Scorers.

Those applying to international matches (referred to as "playing conditions") can be found on the ICC's website.

It is believed to have been a boys' game at that time but, from early in the 17th century, it was increasingly played by adults.

Rules as such existed and, in early times, would have been agreed orally and subject to local variations.

Cricket in the late 17th century became a betting game attracting high stakes and there were instances of teams being sued for non-payment of wagers they had lost.

[3][4][5] In July and August 1727, two matches were organised by stakeholders Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond and Alan Brodrick, 2nd Viscount Midleton.

References to these games confirm that they drew up Articles of Agreement between them to determine the rules that must apply in their contests.

It is among papers which the West Sussex Record Office (WSRO) acquired from Goodwood House in 1884.

[7] This is the first time that rules are known to have been formally agreed, their purpose being to resolve any problems between the patrons during their matches.

The concept, however, was to attain greater importance in terms of defining rules of play as, eventually, these were codified as the Laws of Cricket.

[6] Points that differ from the modern Laws (use of italics is to highlight the differences only): (a) the wickets shall be pitched at twenty three yards distance from each other; (b) that twelve Gamesters shall play on each side; (c) the Batt Men for every one they count are to touch the Umpire's Stick; (d) no Player shall be deemed out by any Wicket put down, unless with the Ball in Hand.

In modern cricket: (a) the pitch is 22 yards long; (b) the teams are eleven-a-side; (c) runs were only completed if the batsman touched the umpire's stick (which was probably a bat) and this practice was eventually replaced by the batsman having to touch the ground behind the popping crease; (d) run outs no longer require the ball to be in hand.

The Laws were drawn up by the "noblemen and gentlemen members of the London Cricket Club", which was based at the Artillery Ground, although the printed version in 1755 states that "several cricket clubs" were involved, having met at the Star and Garter in Pall Mall.

A summary of the main points: The 1744 Laws do not say the bowler must roll (or skim) the ball and there is no mention of prescribed arm action so, in theory, a pitched delivery would have been legal, though potentially controversial.

Underarm pitching is believed to have begun in the early 1760s when the Hambledon Club was rising to prominence.

At the Artillery Ground on 22–23 May 1775, a lucrative single wicket match was played between Five of Kent (with Lumpy Stevens) and Five of Hambledon (with Thomas White).

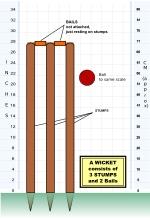

He duly scored the runs and Hambledon won by 1 wicket but a great controversy arose afterwards because, three times in the course of his second innings, Small was beaten by Lumpy only for the ball to pass through the two-stump wicket each time without hitting the stumps or the bail.

By mutual consent between the teams, the pitch could be rolled, watered, covered and mown during a match and the use of sawdust was authorised.

[28][29][30] The first 12 Laws cover the players and officials, basic equipment, pitch specifications and timings of play.

Although it is considered to have unlimited length, the popping crease must be marked to at least 6 feet (1.83 m) on either side of the imaginary line joining the centres of the middle stumps.

This Law contains the rules governing how pitches should be prepared, mown, rolled, and maintained.

The area beyond the pitch where a bowler runs so as to deliver the ball (the 'run-up') should ideally be kept dry so as to avoid injury through slipping and falling, and the Laws also require these to be covered wherever possible when there is wet weather.

A ball can be a no-ball for several reasons: if the bowler bowls from the wrong place; if he straightens his elbow during the delivery; if the bowling is dangerous; if the ball bounces more than once or rolls along the ground before reaching the batter; or if the fielders are standing in illegal places.

Bowlers may only practice bowling and have trial run-ups if the umpires are of the view that it would waste no time and does not damage the ball or the pitch.

However, a batter who is obviously out will normally leave the pitch without waiting for an appeal or a decision from the umpire.

If a batter hits the ball twice, other than for the sole purpose of protecting his wicket or with the consent of the opposition, he is out.

If, after the bowler has entered his delivery stride and while the ball is in play, a batter puts his wicket down by his bat or his body he is out.

If a batter willfully obstructs the opposition by word or action or strikes the ball with a hand not holding the bat, he is out.

A batter is out if at any time while the ball is in play no part of his bat or person is grounded behind the popping crease and his wicket is fairly put down by the opposing side.

There are a number of restrictions to ensure fair play covering: changing the condition of the ball; distracting the batsmen; dangerous bowling; time-wasting; damaging the pitch.