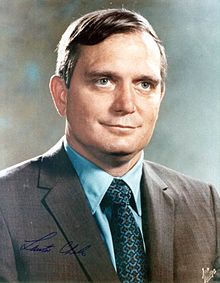

Lawton Chiles

A Korean War veteran, Chiles later returned to Florida for law school and eventually opened his own private practice in 1955.

Following his college years, Chiles entered the Korean War, commissioned as an artillery officer in the United States Army.

After the war, Chiles returned to the University of Florida for law school, from which he graduated in 1955; he passed the state bar exam that year and went into private practice in Lakeland.

To generate some media coverage and meet people across the state, Chiles embarked upon a 1,003-mile, 91-day walk across Florida from Pensacola to Key West.

In later years, Chiles would recall the walk allowed him to see Florida's natural beauty, as well as the state's problems, with fresh eyes.

[5] In the general election campaign, Chiles faced U.S. representative William C. Cramer of St. Petersburg, the first Republican to have served in Congress from Florida since Reconstruction.

Cramer, a graduate of Harvard Law School, questioned Chiles's votes as a state senator on several matters regarding insurance.

[6] The self-made Cramer depicted Chiles as coming from a "silver spoon" background with a then net worth of $300,000, but the media ignored questions about the candidates' personal wealth.

[8] The Tallahassee Democrat forecast correctly that Chiles's "weary feet and comfortable hiking boots" would carry the 40-year-old "slow-country country lawyer" with "boyish amiability", and "back-country common sense and methodical urbane political savvy" to victory.

[9] Chiles's "Huck Finn" image was contrasted one night in Miami when he held a fried chicken picnic while the Republicans showcased a black-tie $1,000-a-plate dinner.

"[10] With "shoe leather and a shoestring budget", Chiles presented himself as a "problem solver who doesn't automatically vote 'No' on every issue.

But the press was enamored with the walk ... Every time he was asked a question about where he stood, he would quote somebody that he met on the campaign trail to state what he was to do when he got to the Senate consistent with what that constituent had said.

By contrast, Cramer received little credit from environmentalists although he had drafted the Water Pollution Control Act of 1956 and had sponsored legislation to protect alligators, stop beach erosion, dredge harbors, and remove oil spills.

Cramer questioned Chiles's opposition to a proposed severance tax on phosphate mining, which particularly impacted Tampa Bay.

[16] In the face of media opposition, Cramer failed to pin the "liberal" label on Chiles, who called himself by the rare hybrid term "progressive conservative.

"[17] Explaining Cramer's inability to make "liberalism" an issue in 1970, The New York Times observed that Chiles and the gubernatorial candidate, Reubin Askew of Pensacola, "convey amiable good ol' boy qualities with moderate-to-liberal aspirations that do not strike fear into the hearts of conservatives.

He noted that Cramer had expected to face former governor Farris Bryant, who like LeRoy Collins, Gurney's foe in 1968, had ties to the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Chiles, however, retorted that if Republicans controlled the Senate other southern Democrats would also forfeit committee chairmanships earned through their seniority.

During the Democratic Party primary, his opponent Bill Nelson attempted to make an issue of Chiles' age and health, a strategy that backfired badly in a state with a large population of retirees.

The early years of his term were troubled by a national economic recession that severely damaged Florida's tourism-based economy, and by Hurricane Andrew, which struck near Homestead in August 1992.

[28] During the campaign season, Bush ran a television advertisement which featured the mother of a teenage girl who had been abducted and murdered many years before.

Moreover, after the botched electrocution of Pedro Medina in 1997, and despite significant public criticism, Chiles refused to endorse the use of lethal injection as a lawful form of execution.

During the last debate on November 1, Chiles said to Bush, "My momma told me, sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will never hurt me.

Governor Buddy MacKay explained that the he-coon was the oldest and wiliest raccoon in the pack, according to Florida cracker folklore.

[33] The quip was a direct appeal to older, rural, ancestral Floridians, whose loyalty to Democratic candidates had waned over the past several decades.

In 1995, Chiles sought treatment for a neurological problem that was later diagnosed as a mild stroke after he awoke with nausea, slurred speech and loss of coordination; and it would be determined dehydration might have caused the episode.

On December 12 that year, just three weeks before his long-awaited retirement was to begin, Chiles suffered from an abnormal heart rhythm[39] while exercising on a cycling machine in the Governor's Mansion gymnasium.

He emphasized health coverage for the uninsured and led a campaign to create the National Commission for Prevention of Infant Mortality in the late 1980s.

One of the significant recommendations that came from that commission eventually led to the highly controversial 2002 state constitutional amendment restricting Florida's school class sizes.

[citation needed] In 1997, anti-abortion advocacy group Choose Life collected 10,000 signatures and filed the $30,000 fee required under Florida law at the time to submit an application for a new specialty plate.