Le Marteau sans maître

Before Le Marteau, Boulez had established a reputation as the composer of modernist and serialist works such as Structures I, Polyphonie X, as well as his infamously "unplayable" Second Piano Sonata.

[4] Boulez, notorious for considering his works to be always "in progress", made further, smaller revisions to Le Marteau in 1957, in which year Universal Edition issued an engraved score, UE 12450.

When asked to supply program notes for the first performance of Le Marteau in 1955 at the Baden-Baden International Society for Contemporary Music, Boulez laconically wrote, as quoted by Friederich Saathen: "Le Marteau sans Maître, after a text by René Char, written for alto, flute, viola, guitar, vibraphone, and percussion.

[7] This is partially due to the fact that Boulez believes in strict control tempered with "local indiscipline", or rather, the freedom to choose small, individual elements while still adhering to an overall structure compatible with serialist principles.

The xylorimba recalls the African balafon; the vibraphone, the Balinese gamelan; and the guitar, the Japanese koto, though "neither the style nor the actual use of these instruments has any connection with these different musical civilizations".

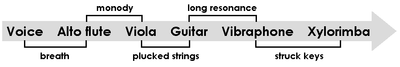

[9] Boulez chose the collection with a continuum of sonorities in mind: "a number of features shared by these instruments (forms) a continuous passage from voice to vibraphone".

The voice and five pitched instruments can be arranged in a line, each pair connected by a similarity, as in the following diagram:[11] The vocal writing is challenging for the singer, containing wide leaps, glissandi, humming (notated bouche fermée in the score),[vague] and even Sprechstimme, a device found in the work of the Second Viennese School before Boulez.

There are also deliberate similarities to Arnold Schoenberg's song cycle, Pierrot Lunaire,[12] one of which is that each movement chooses a different subset of the available instruments: The opening of the third movement in the flute is typical of the difficulties required of performers including wide range, large leaps, and complex rhythms: Boulez uses many serial composition techniques, including pitch multiplication and pitch-class association.

Koblyakov's analysis reveals that the harmonic fields Boulez employs at certain parts of the piece are laid out very systematically, showing that the movements' overall forms are complexly mathematical as well.

However, both of these movements play essential roles in the piece, especially when one takes into account the extreme levels of symmetry and pattern employed by Boulez in his composition of the work.

The red caravan on the edge of the nail And corpse in the basket And plowhorses in the horseshoe I dream the head on the point of my knife Peru.

I hear marching in my legs The dead sea waves overhead Child the wild seaside pier Man the imitated illusion Pure eyes in the woods Are searching in tears for a habitable head.

Le Marteau sans maître was hailed by critics, fellow composers, and other musical experts as a masterpiece of the post-war avant-garde from its first performance in 1955.

Interviewed in 2014, the composer Harrison Birtwistle declared that Le Marteau sans maître "is the kind of piece, in all the noise of contemporary music that's gone on in my lifetime, I'd like to have written".

[25] One of the most enthusiastic and influential early testimonials came from Igor Stravinsky, who praised the work as an exemplar of "a new and wonderfully supple kind of music".

[26] However, according to Howard Goodall, the sixty years since its première have failed to grant Le marteau an equally enthusiastic endorsement from the general public.

[27] Despite its attractive surface, its "smooth sheen of pretty sounds",[28] issues remain about the music's deeper comprehensibility for the ordinary listener.

[29] But if we are supposed not to listen in the tonal-harmonic sense, what exactly is it that we should hear and understand in a work which, in the words of Alex Ross, features "nothing so vulgar as a melody or a steady beat"?

[33] Roger Scruton finds Boulez's preoccupation with timbre and sonority in the instrumental writing has the effect of preventing "simultaneities from coalescing as chords".

[34] As a result, Scruton says that, especially where pitches are concerned, Le Marteau "contains no recognizable material – no units of significance that can live outside the work that produces them".

[35] Scruton also feels that the involved overlapping metres notated in the score beg "a real question as to whether we hear the result as a rhythm at all".

[36] Richard Taruskin found "Le Marteau exemplified the lack of concern on the part of modernist composers for the comprehensibility of their music".

[37] Equally bluntly, Christopher Small, writing in 1987 said "It is not possible to invoke any 'inevitable time lag' which is supposed to be required for the assimilation of ...such critically acclaimed works as...