Leader of the Opposition (United Kingdom)

The emergence of the office thus coincided with the period when wholly united parties (Whig and Tory, governments and oppositions) became the norm.

[7] This situation was normalized in the Parliament of 1807–1812 when the members of the Grenvillite and Foxite Whig factions resolved to maintain a joint, dual-house leadership for the whole party.

[7] Grenville's article in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography confirms that he was considered the Whig leader in the House of Lords between 1807 and 1817, despite Grey leading the larger faction.

Grenville and Grey, political historian Archibald Foord describe as being "duumvirs of the party from 1807 to 1817" and consulted about what was to be done.

Eventually, they jointly recommended George Ponsonby to the Whig MPs, whom they accepted as the first leader of the opposition in the House of Commons.

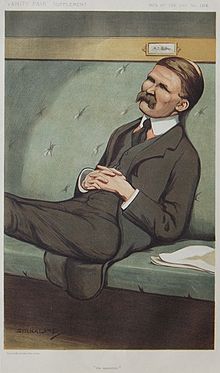

Ponsonby, an Irish lawyer who was the uncle of Grey's wife, had been Lord Chancellor of Ireland during the Ministry of all the Talents and had only just been re-elected to the House of Commons in 1808 when he became leader.

[7] Ponsonby proved a weak leader but as he could not be persuaded to resign and the duumvirs did not want to depose him, he remained in place until he died in 1817.

Grey was not a former prime minister in 1817, unlike Grenville, so under the convention that developed later in the century he would have been in the theory of equal status to whoever was a leader in the other House.

However, there was little doubt that if a Whig ministry was possible, Grey rather than the less distinguished Commons leaders would have been invited to form that government.

In this respect Grey's position was like that of the Earl of Derby in the Protectionist Conservative opposition of the late 1840s and early 1850s.

This motion was defeated by 357 to 178, a division involving the largest number of MPs until the debates over the Reform bill in the early 1830s.

Following the retirement of Lord Liverpool from the prime ministership in 1827, the party's political situation changed.

As a result, Canning found it difficult to maintain a government and chose to invite a number of Whigs to join his Cabinet, including Lord Lansdowne.

[8] The Duke of Wellington formed a ministry in January 1828 and as a direct effect of adopting in earnest the policy of Catholic Emancipation the opposition became composed of most Whigs with many Canningites and some ultra-Tories.

In the period of 1830–1937, the normal expectation was that there would be two leading parties (often with smaller allied groups), of which one would form the government and the other the opposition.

As the monarch retained some discretion as to which leader should be invited to form a ministry, it was not always obvious in advance which one would be called upon to do so.

He was the only established front-rank political figure in the faction and thus a very strong candidate to form the next Conservative ministry.

Lord George Bentinck, the leader of the Protectionist revolt against Sir Robert Peel, initially led the party in the Commons.

The first attempt to square the circle was made in February 1848, when the young Marquess of Granby was installed as the leader.

The next experiment was to entrust the leadership to a triumvirate of Granby, Disraeli, and the elderly John Charles Herries.

The Leader of the Liberal Party, H. H. Asquith, and most of his leading colleagues left the government and took up seats on the opposition side of the House of Commons.

Erskine May: Parliamentary Practice confirms that the office of the leader of the opposition was first given statutory recognition in the Ministers of the Crown Act 1937.

The holder also receives a chauffeur-driven car for official business of equivalent cost and specification to the vehicles used by most cabinet ministers.

In 1940 the three largest parties in the House of Commons formed a coalition government to continue to prosecute the Second World War.

Keesing's Contemporary Archives 1937–1940 (at paragraph 4069D) reported the situation, based on Hansard: The Prime Minister replying to Mr. Denman in the House of Commons on 21 May, said that in view of the formation of an Administration embracing the three main political parties, H.M. Government was of the opinion that the provision of the Ministers of the Crown Act, 1937, relating to the payment of a salary to the leader of the opposition was in abeyance for the time being, as there was no alternative party capable of forming a Government.

The Daily Herald reported that the Parliamentary Labour Party met on 22 May 1940 and unanimously elected Dr H.B.

After the death of Lees-Smith, on 18 December 1941, the PLP with Patrick McFadden acting as chairman, held a meeting on 21 January 1942.

The table lists the people who were, or who acted as, leaders of the opposition in the two Houses of Parliament since 1807, prior to which the post was held by Charles James Fox for decades.

This list notes each Leader of the Opposition, from the Parliament Act 1911 granting legislative preeminence to the House of Commons,[10] and the Ministers of the Crown Act 1937 the leader of the second largest faction within it a statutory title and salary,[11] rather than the customary role as HM Official Opposition,[12] in order of term length.