League of Nations

[2] Its other concerns included labour conditions, just treatment of native inhabitants, human and drug trafficking, the arms trade, global health, prisoners of war, and protection of minorities in Europe.

The League lacked its own armed force and depended on the victorious Allied Powers of World War I (Britain, France, Italy and Japan were the initial permanent members of the Council) to enforce its resolutions, keep to its economic sanctions, or provide an army when needed.

Current scholarly consensus views that, even though the League failed to achieve its main goal of world peace, it did manage to build new roads towards expanding the rule of law across the globe; strengthened the concept of collective security, gave a voice to smaller nations; fostered economic stabilisation and financial stability, especially in Central Europe in the 1920s; helped to raise awareness of problems such as epidemics, slavery, child labour, colonial tyranny, refugee crises and general working conditions through its numerous commissions and committees; and paved the way for new forms of statehood, as the mandate system put the colonial powers under international observation.

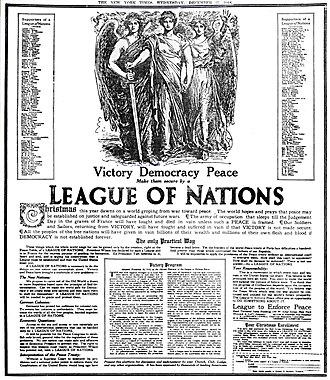

The delegates adopted a platform calling for creation of international bodies with administrative and legislative powers to develop a "permanent league of neutral nations" to work for peace and disarmament.

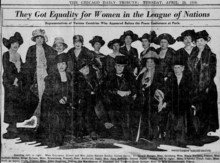

Coordinated by Mia Boissevain, Aletta Jacobs and Rosa Manus, the congress, which opened on 28 April 1915[25] was attended by 1,136 participants from neutral nations,[26] and resulted in the establishment of an organisation which would become the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF).

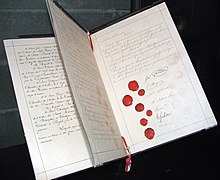

Methods of compulsion against recalcitrant states would include severe measures, such as "blockading and closing the frontiers of that power to commerce or intercourse with any part of the world and to use any force that may be necessary..."[37] The two principal drafters and architects of the covenant of the League of Nations[39] were the British politician Lord Robert Cecil and the South African statesman Jan Smuts.

There was not a good fit between Wilson's "revolutionary conception of the League as a solid replacement for a corrupt alliance system, a guardian of international order, and protector of small states," versus Lloyd George's desire for a "cheap, self-enforcing, peace, such as had been maintained by the old and more fluid Concert of Europe.

"[64] Furthermore, the League, according to Carole Fink, was, "deliberately excluded from such great-power prerogatives as freedom of the seas and naval disarmament, the Monroe Doctrine and the internal affairs of the French and British empires, and inter-Allied debts and German reparations, not to mention the Allied intervention and the settlement of borders with Soviet Russia.

Ludovic Tournès argues that by the 1930s the foundations had changed the League from a "Parliament of Nations" to a modern think tank that used specialised expertise to provide an in-depth impartial analysis of international issues.

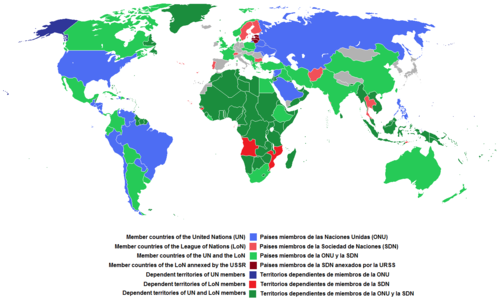

Through the first half of the 1930s, six more states joined, including Iraq in 1932 (newly independent from a League of Nations mandate)[70] and the Soviet Union on 18 September 1934,[71] but the Empire of Japan and Germany (under Hitler) withdrew in 1933.

[80] Its principal sections were Political, Financial and Economics, Transit, Minorities and Administration (administering the Saar and Danzig), Mandates, Disarmament, Health, Social (Opium and Traffic in Women and Children), Intellectual Cooperation and International Bureaux, Legal, and Information.

[121] The Paris Peace Conference compromised with Wilson by adopting the principle that these territories should be administered by different governments on behalf of the League – a system of national responsibility subject to international supervision.

[121][122] This plan, defined as the mandate system, was adopted by the "Council of Ten" (the heads of government and foreign ministers of the main Allied Powers: Britain, France, the United States, Italy, and Japan) on 30 January 1919 and transmitted to the League of Nations.

The A mandates (applied to parts of the old Ottoman Empire) were "certain communities" that had ...reached a stage of development where their existence as independent nations can be provisionally recognised subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory until such time as they are able to stand alone.

These were described as "peoples" that the League said were ...at such a stage that the Mandatory must be responsible for the administration of the territory under conditions which will guarantee freedom of conscience and religion, subject only to the maintenance of public order and morals, the prohibition of abuses such as the slave trade, the arms traffic and the liquor traffic, and the prevention of the establishment of fortifications or military and naval bases and of military training of the natives for other than police purposes and the defence of territory, and will also secure equal opportunities for the trade and commerce of other Members of the League.

[152] This heightened tension between Lithuania and Poland and led to fears that they would resume the Polish–Lithuanian War, and on 7 October 1920, the League negotiated the Suwałki Agreement establishing a cease-fire and a demarcation line between the two nations.

The report implicated many government officials in the selling of contract labour and recommended that they be replaced by Europeans or Americans, which generated anger within Liberia and led to the resignation of President Charles D. B.

[178] In the end, as British historian Charles Mowat argued, collective security was dead: The League failed to prevent the 1932 war between Bolivia and Paraguay over the arid Gran Chaco region.

Although the region was sparsely populated, it contained the Paraguay River, which would have given either landlocked country access to the Atlantic Ocean,[180] and there was also speculation, later proved incorrect, that the Chaco would be a rich source of petroleum.

[187] Marshal Pietro Badoglio led the campaign from November 1935, ordering bombing, the use of chemical weapons such as mustard gas, and the poisoning of water supplies, against targets which included undefended villages and medical facilities.

[195] The Abyssinian crisis showed how the League could be influenced by the self-interest of its members;[196] one of the reasons why the sanctions were not very harsh was that both Britain and France feared the prospect of driving Mussolini and Adolf Hitler into an alliance.

[198] Julio Álvarez del Vayo, the Spanish Minister of Foreign Affairs, appealed to the League in September 1936 for arms to defend Spain's territorial integrity and political independence.

[220] The League was mostly silent in the face of major events leading to the Second World War, such as Hitler's remilitarisation of the Rhineland, occupation of the Sudetenland and Anschluss of Austria, which had been forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles.

This problem mainly stemmed from the fact that the primary members of the League of Nations were not willing to accept the possibility of their fate being decided by other countries and (by enforcing unanimous voting) had effectively given themselves veto power.

On 23 June 1936, in the wake of the collapse of League efforts to restrain Italy's war against Abyssinia, the British Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, told the House of Commons that collective security had failed ultimately because of the reluctance of nearly all the nations in Europe to proceed to what I might call military sanctions ...

It has been a failure, not because the United States did not join it; but because the great powers have been unwilling to apply sanctions except where it suited their individual national interests to do so, and because Democracy, on which the original concepts of the League rested for support, has collapsed over half the world.

[244] As the situation in Europe escalated into war, the Assembly transferred enough power to the Secretary General on 30 September 1938 and 14 December 1939 to allow the League to continue to exist legally and carry on reduced operations.

"[253] A Board of Liquidation consisting of nine persons from different countries spent the next 15 months overseeing the transfer of the League's assets and functions to the United Nations or specialised bodies, finally dissolving itself on 31 July 1947.

Current consensus views that, even though the League failed to achieve its ultimate goal of world peace, it did manage to build new roads towards expanding the rule of law across the globe; strengthened the concept of collective security, giving a voice to smaller nations; helped to raise awareness to problems like epidemics, slavery, child labour, colonial tyranny, refugee crises and general working conditions through its numerous commissions and committees; and paved the way for new forms of statehood, as the mandate system put the colonial powers under international observation.

[256] Alternatively, Laura Robson & Joe Maiolo posit the argument that the Mandate System under the League was a re-vitalised form of imperialism that placed former colonies under the ownership of greater powers.