Lee wave

These were discovered in 1933 by two German glider pilots, Hans Deutschmann and Wolf Hirth, above the Giant Mountains.

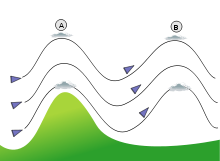

[5] Usually a turbulent vortex, with its axis of rotation parallel to the mountain range, is generated around the first trough; this is called a rotor.

Buoyancy restoring forces therefore act to excite a vertical oscillation of the perturbed air parcels at the Brunt-Väisäla frequency, which for the atmosphere is:

These air parcel oscillations occur in concert, parallel to the wave fronts (lines of constant phase).

These wave fronts represent extrema in the perturbed pressure field (i.e., lines of lowest and highest pressure), while the areas between wave fronts represent extrema in the perturbed buoyancy field (i.e., areas most rapidly gaining or losing buoyancy).

Lee waves provide a possibility for gliders to gain altitude or fly long distances when soaring.

World record wave flight performances for speed, distance or altitude have been made in the lee of the Sierra Nevada, Alps, Patagonic Andes, and Southern Alps mountain ranges.

[16][17][18] The conditions favoring strong lee waves suitable for soaring are: The rotor turbulence may be harmful for other small aircraft such as balloons, hang gliders and paragliders.

It can even be a hazard for large aircraft; the phenomenon is believed responsible for many aviation accidents and incidents, including the in-flight breakup of BOAC Flight 911, a Boeing 707, near Mount Fuji, Japan in 1966, and the in-flight separation of an engine on an Evergreen International Airlines Boeing 747 cargo jet near Anchorage, Alaska in 1993.

[19] The rising air of the wave, which allows gliders to climb to great heights, can also result in high-altitude upset in jet aircraft trying to maintain level cruising flight in lee waves.

Rising, descending or turbulent air, in or above the lee waves, can cause overspeed, stall or loss of control.