Leedsichthys

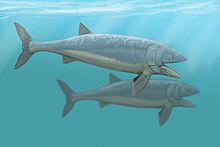

Leedsichthys is an extinct genus of pachycormid fish that lived in the oceans of the Middle to Late Jurassic.

In 1999, based on the Chilean discoveries, a second species was named Leedsichthys notocetes, but this was later shown to be indistinguishable from L. problematicus.

Along with its close pachycormid relatives Bonnerichthys and Rhinconichthys, Leedsichthys is part of a lineage of large-sized filter-feeders that swam the Mesozoic seas for over 100 million years, from the middle Jurassic until the end of the Cretaceous period.

During the 1880s, the gentleman farmer Alfred Nicholson Leeds collected large fish fossils from loam pits near Peterborough, England.

[3] On 22 August 1888, the American dinosaur expert Professor Othniel Charles Marsh visited Leeds' farm at Eyebury and quickly concluded that the presumed dinosaurian armour in fact represented the skull bones of a giant fish.

Within two weeks British fish expert Arthur Smith Woodward examined the specimens and began to prepare a formal description published in 1889.

[1] The fossils found by Leeds gave the fish the specific epithet problematicus because the remains were so fragmented that they were extremely hard to recognize and interpret.

[1] The holotype specimen, BMNH P.6921, had been found in a layer of the Oxford Clay Formation dating from the Callovian, about 165 million years old.

It consists of 1133 disarticulated elements of the skeleton, mostly fin ray fragments, probably of a single individual.

Woodward also identified a specimen previously acquired from the French collector Tesson, who had in 1857 found them in the Falaises des Vaches Noires of Normandy, BMNH 32581, as the gill rakers of Leedsichthys.

[10] From 2002 until 2004 "Ariston" or specimen PETMG F174 was excavated by a team headed by Jeff Liston; to uncover the remains it was necessary to remove ten thousand tonnes of loam forming an overburden of 15 metres (49 feet) thickness.

Liston subsequently dedicated a dissertation and a series of articles to Leedsichthys, providing the first extensive modern osteology of the animal.

In July 1982, Germany became an important source of Leedsichthys fossils when two groups of amateur palaeontologists, unaware of each other's activities, began to dig up the same skeleton at Wallücke.

[7] A complete and isolated gill raker from the Vaca Muerta formation of Argentina (MOZ-Pv 1788), has been assigned to the genus and dates to the early Tithonian.

This is largely caused by the fact that many skeletal elements, including the front of the skull and the vertebral centra, did not ossify but remained cartilage.

In the fossil phase, compression flattened and cracked these hollow structures, making it extraordinarily difficult to identify them or determine their original form.

The hypobranchials are attached at their lower ends at an angle of 21,5° via a functional joint that possibly served to increase the gape of the mouth, to about two feet.

Detailed study of exquisitely preserved French specimens revealed to Liston that these teeth were, again via soft tissue, each attached to delicate 2-millimetre-long (0.08-inch-long) bony plates, structures that had never before been observed among living or extinct fishes.

An earlier hypothesis that the striations would function as sockets for sharp "needle teeth", as with the basking shark, was hereby refuted.

They are large, very elongated — about five times longer than wide — and scythe-like, with a sudden kink at the lower end, curving 10° to the rear.

The length of Leedsichthys was not historically the subject of much attention, the only reference to it being made by Woodward himself when he in 1937 indicated it again as 9 metres (30 feet) on the museum label of BMNH P.10000.

Documentation of historical finds[25] and the excavation of "Ariston", the most complete specimen ever from the Star Pit near Whittlesey, Peterborough,[26] support Woodward's figures of between 9 and 10 metres (30 and 33 ft).

The growth ring structures within the remains of Leedsichthys have indicated that it would have taken 21 to 25 years to reach these lengths,[28] and isolated elements from other specimens showed that a maximum size of just over 16 m (52 ft)[29] is not unreasonable.

[30] Woodward initially assigned Leedsichthys to the Acipenseroidea, considering it related to the sturgeon, having the large gill rakers and branching finrays in common.

[34] †Pteronisculus †Discoserra pectinodon †Watsonulus eugnathoides †Macrepistius rostratus †Caturus Amia calva Lepisosteus platostomus †Macrosemius rostratus †Semionotus elegans †Lepidotes †Pholidophorus bechei Elops hawaiensis Hiodon alosoides †Euthynotus †Hypsocormus insignis †"Hypsocormus" tenuirostris †Orthocormus †Australopachycormus hurleyi †Protosphyraena †Pachycormus †Asthenocormus titanius †Martillichthys renwickae †Bonnerichthys gladius †Leedsichthys problematicus †Rhinconichthys taylori Like the largest fish today, the whale sharks and basking sharks, Leedsichthys problematicus derived its nutrition as a suspension feeder, using an array of specialised gill rakers lining its gill basket to extract zooplankton, small animals, from the water passing through its mouth and across its gills.

In 2010, Liston suggested that fossilised furrows discovered in ancient sea floors in Switzerland and attributed to the activity of plesiosaurs, had in fact been made by Leedsichthys spouting water through its mouth to disturb and eat the benthos, the animals dwelling in the sea floor mud.

In 1999 Martill suggested that a climate change at the end of the Callovian led to the extinction of Leedsichthys in the northern seas, the southern Ocean offering a last refuge during the Oxfordian.

Indeed, further studies supported this, viewing Leedsichthys as the beginning of a long line of large (>2 metres (6.6 feet) in length) pachycormid suspension feeders that continued to flourish well into the Late Cretaceous, such as Bonnerichthys and Rhinconichthys,[39] and emphasising the convergent evolutionary paths taken by pachycormids and baleen whales.

Using data from living teleost fish as a comparison, scientists discovered that Leedsichthys could have cruised along at potential speeds of 11 mph (17.8 km/h) while still maintaining oxygenation of its body tissues.