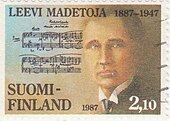

Leevi Madetoja

Leevi Antti Madetoja (pronounced [ˈleːʋi ˈmɑdetˌojɑ];[1] 17 February 1887 – 6 October 1947) was a Finnish composer, music critic, conductor, and teacher of the late-Romantic and early-modern periods.

The core of Madetoja's oeuvre consists of a set of three symphonies (1916, 1918, and 1926), arguably the finest early-twentieth century additions to the symphonic canon of any Finnish composer, Sibelius excepted.

Other notable works include an Elegia for strings (1909); Kuoleman puutarha (The Garden of Death, 1918–21), a three-movement suite for solo piano; the Japanisme ballet-pantomime, Okon Fuoko (1927); and, a second opera, Juha (1935).

His idiom is notably introverted for a national Romantic composer, a blend of Finnish melancholy, folk melodies from his native region of Ostrobothnia, and the elegance and clarity of the French symphonic tradition, founded on César Franck and guided by Vincent d'Indy.

[6] His public introduction arrived in January 1910 when Robert Kajanus, chief conductor of the Helsinki Orchestral Society, conducted Madetoja's Elegia (from the four-movement Symphonic Suite, Op.

[7] With funding from the Finnish government and a letter of introduction from Sibelius, Madetoja applied to be a student of Vincent d'Indy, who headed a school of thought founded upon the symphonic principles of César Franck.

[10] Madetoja found the group in a state of devastation: he was able to piece together 19 musicians, a reality that forced him to spend much of his time finding and arranging material for such an undersized ensemble.

[15] While juggling his responsibilities in Viipuri, Madetoja worked on his most first major compositions, the First Symphony in Helsinki (Kajanus the dedicatee), conducting the premiere on 10 February 1916; apparently he completed the finale just before this performance.

Despite the trifling salary, the post held great prestige,[23] having previously been the chair of Fredrik Pacius (1835–69),[24] Richard Faltin [fi] (1870–96),[25] and (controversially) Kajanus (1897–27),[26] and included among its tasks the conductorship of the Academic Orchestra.

Although Kuula viewed the play as a strong candidate for a libretto, its realism conflicted with his personal preference for fairy tale or legend-based subject matter, in keeping with the Wagnerian operatic tradition.

The composition process, begun in late December 1917, took Madetoja much longer than expected; letters to his mother indicate that he had entertained hopes of completing the opera by the end of 1920 and, when this deadline passed, 1921 and, eventually, 1922.

Indeed, with The Ostrobothnians, Madetoja succeeded where his teacher, Jean Sibelius, famously had failed: in the creation of a Finnish national opera, a watershed moment for a country lacking an operatic tradition of its own.

[30] The Ostrobothnians immediately became a fixture of the Finnish operatic repertoire (where it remains today), and was even produced abroad during Madetoja's lifetime, in Kiel, Germany in 1926; Stockholm in 1927; Gothenburg in 1930; and, Copenhagen in 1938.

[34] The production languished unperformed until it (finally) received its premiere on 12 February 1930, not in Copenhagen, but rather in Helsinki, at the Finnish National Opera under the baton of Martti Similä [fi].

[43] As the Fourth's finish line neared in the spring of 1938, Madetoja traveled to Nice hoping that France, as it had a decade earlier with the Third Symphony, would stoke his creative fires.

[44] Misfortune quickly dashed Madetoja's hopes: while passing through Paris on his way to Southern France, his suitcase—which contained the Fourth Symphony—was stolen at a railway station in the city; the near-completed manuscript was never recovered.

[44] With his inspiration and memory in decline, Madetoja never undertook a reconstruction of the lost score, notwithstanding his (unsuccessful) 1941 application for a stipend to "finish my fourth symphony that is underway".

[47] The Madetoja funeral took place five days later on 11 October at the Helsinki Old Church; the president of Finland, Juho Kusti Paasikivi, supplied a wreath, as did the Ministry of Education, the City of Oulu, and other institutions and mourners.

[citation needed][n 13] Madetoja left (very early) plans for a number of never-realized works, including a violin concerto, a requiem mass, a third opera (a "Finnish Parsifal"), and Ikävyys (Melancholy), a composition for voice and piano after Aleksis Kivi.

[48] Madetoja (joined by Onerva in 1972) is buried at Hietaniemi cemetery (Hietaniemen hautausmaa) in Helsinki, a national landmark and frequent tourist attraction that features the graves of famous Finnish military figures, politicians, and artists.

[55][n 15] Later in life, during Sibelius's fiftieth birthday celebrations, Madetoja recounted the way in which he had, as a young man, reacted to the news: I still clearly remember with what real feeling of joy and respect I received the information that I had been accepted as a student of Sibelius—I thought I was seeing a beautiful dream.

[70] Despite his conducting duties in Viipuri and the stress of composing his First Symphony, Madetoja sought to take on yet another commitment: to write the first Finnish language biography of Sibelius in honor of the master's fiftieth birthday in 1915.

Things have come to a pretty poor state when our publishers are so cautious, and think only of their wretched balance sheets, when a project of this importance concerning our greatest composer is proposed.

I hope, however, you won't be angry with me, even though I have troubled you so much over this project.As a result, the biography was abandoned and Madetoja settled for a piece in Helsingin sanomat in which he took other critics to task for having overlooked the "absolute, pure" qualities of Sibelius's music.

Stylistically, Madetoja belongs to the national Romantic school,[5][62][74] along with Finnish contemporaries Armas Järnefelt, Robert Kajanus, Toivo Kuula, Erkki Melartin, Selim Palmgren, and Jean Sibelius;[75] with the exception of Okon Fuoko, Madetoja's music, darkly colored but tonal, is not particularly modernist in outlook, certainly not when compared directly with the outputs of Uuno Klami, Aarre Merikanto, Ernest Pingoud, and Väinö Raitio.

[76] For a Romantic composer, however, Madetoja's music is notably "introverted",[5] avoiding the excesses characteristic of that art movement in favor of the "balance, clarity, refinement of expression, and technical polish" of classicism.

The Third, in A major, is optimistic and pastorale in character, as well as "more restrained" than the Second, is today considered one of the finest symphonies in the Finnish orchestral canon, indeed a "masterpiece ... equal in stature" to Sibelius's seven essays in the form.

[22] Part of this neglect is not unique to Madetoja: the titanic legacy of Sibelius has made it difficult for Finnish composers (especially his contemporaries), as a group, to gain much attention, and each has had to labor under his "dominating shadow".

Despite these projects, a large portion of Madetoja's oeuvre nevertheless remains unrecorded, the most notable omissions being the cantatas, a few neglected pieces for voice and orchestra, and the handful of compositions for chamber ensemble.

[86] Reviewing the Ondine song collection for Fanfare, Jerry Dubins notes music's nuanced emotional range, as Madetoja achieves "moments of soaring ecstasy and searing pain", but without recourse to "sentimental" or "cloying" ornamentation.