Adjoint functors

In many situations, an adjunction can be "upgraded" to an equivalence, by a suitable natural modification of the involved categories and functors.

In the classic text Categories for the Working Mathematician, Mac Lane makes a distinction between the two.

In a sense, an adjoint functor is a way of giving the most efficient solution to some problem via a method that is formulaic.

This is rather vague, though suggestive, and can be made precise in the language of category theory: a construction is most efficient if it satisfies a universal property, and is formulaic if it defines a functor.

The idea of using an initial property is to set up the problem in terms of some auxiliary category E, so that the problem at hand corresponds to finding an initial object of E. This has an advantage that the optimization—the sense that the process finds the most efficient solution—means something rigorous and recognisable, rather like the attainment of a supremum.

(Note that this is precisely the definition of the comma category of R over the inclusion of unitary rings into rng.)

The existence of a morphism between R → S1 and R → S2 implies that S1 is at least as efficient a solution as S2 to our problem: S2 can have more adjoined elements and/or more relations not imposed by axioms than S1.

Therefore, the assertion that an object R → R* is initial in E, that is, that there is a morphism from it to any other element of E, means that the ring R* is a most efficient solution to our problem.

The two facts that this method of turning rngs into rings is most efficient and formulaic can be expressed simultaneously by saying that it defines an adjoint functor.

The theory of adjoints has the terms left and right at its foundation, and there are many components that live in one of two categories C and D that are under consideration.

These definitions via universal morphisms are often useful for establishing that a given functor is left or right adjoint, because they are minimalistic in their requirements.

and two natural transformations respectively called the counit and the unit of the adjunction (terminology from universal algebra), such that the compositions are the identity morphisms

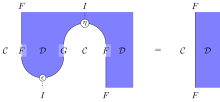

They are sometimes called the triangle identities, or sometimes the zig-zag equations because of the appearance of the corresponding string diagrams.

Note: The use of the prefix "co" in counit here is not consistent with the terminology of limits and colimits, because a colimit satisfies an initial property whereas the counit morphisms satisfy terminal properties, and dually for limit versus unit.

[2] Like many of the concepts in category theory, it was suggested by the needs of homological algebra, which was at the time devoted to computations.

Those faced with giving tidy, systematic presentations of the subject would have noticed relations such as in the category of abelian groups, where F was the functor

The use of the equals sign is an abuse of notation; those two groups are not really identical but there is a way of identifying them that is natural.

One can verify directly that this correspondence is a natural transformation, which means it is a hom-set adjunction for the pair (F,G).

is the set map from GFGX to GX, which underlies the group homomorphism sending each generator of FGX to the element of X it corresponds to ("dropping parentheses").

Any Galois connection gives rise to closure operators and to inverse order-preserving bijections between the corresponding closed elements.

As is the case for Galois groups, the real interest lies often in refining a correspondence to a duality (i.e. antitone order isomorphism).

A treatment of Galois theory along these lines by Kaplansky was influential in the recognition of the general structure here.

The partial order case collapses the adjunction definitions quite noticeably, but can provide several themes: The twin fact in probability can be understood as an adjunction: that expectation commutes with affine transform, and that the expectation is in some sense the best solution to the problem of finding a real-valued approximation to a distribution on the real numbers.

There are hence numerous functors and natural transformations associated with every adjunction, and only a small portion is sufficient to determine the rest.

Given a right adjoint functor G : C → D; in the sense of initial morphisms, one may construct the induced hom-set adjunction by doing the following steps.

A similar argument allows one to construct a hom-set adjunction from the terminal morphisms to a left adjoint functor.

G, we can construct a hom-set adjunction by finding the natural transformation Φ : homC(F-,-) → homD(-,G-) in the following steps: Given functors F : D → C, G : C → D, and a hom-set adjunction Φ : homC(F-,-) → homD(-,G-), one can construct a counit–unit adjunction which defines families of initial and terminal morphisms, in the following steps: Not every functor G : C → D admits a left adjoint.

However, universal constructions are more general than adjoint functors: a universal construction is like an optimization problem; it gives rise to an adjoint pair if and only if this problem has a solution for every object of D (equivalently, every object of C).

Every adjunction 〈F, G, ε, η〉 gives rise to an associated monad 〈T, η, μ〉 in the category D. The functor is given by T = GF.

Dually, the triple 〈FG, ε, FηG〉 defines a comonad in C. Every monad arises from some adjunction—in fact, typically from many adjunctions—in the above fashion.