Midfielder

Prominent central midfielders are known for their ability to pace the game when their team is in possession of the ball, by dictating the tempo of play from the centre of the pitch.

[9] Some notable examples of box-to-box midfielders are Lothar Matthäus, Clarence Seedorf, Bastian Schweinsteiger, Steven Gerrard, Johan Neeskens, Sócrates, Yaya Touré, Arturo Vidal, Patrick Vieira, Frank Lampard, Bryan Robson, Roy Keane, and more recently, Jude Bellingham.

The term was initially applied to the role of an inside forward in the WM and Metodo formations in Italian, but later described a specific type of central midfielder.

The Mezzala is often a quick and hard-working attack-minded midfielder, with good skills and noted offensive capabilities, as well as a tendency to make overlapping attacking runs, but also a player who participates in the defensive aspect of the game, and who can give width to a team by drifting out wide; as such, the term can be applied to several different roles.

[18] Jonathan Wilson describes the development of the 4−4−2 formation: "…the winger became a wide midfielder, a shuttler, somebody who might be expected to cross a ball but was also meant to put in a defensive shift.

[28][29] Sergio Busquets described his attitude: "The coach knows that I am an obedient player who likes to help out and if I have to run to the wing to cover someone's position, great.

[34] The latest and third type of holding midfielder developed as a box-to-box midfielder, or "carrier" or "surger", neither entirely destructive nor creative, who is capable of winning back possession and subsequently advancing from deeper positions either by distributing the ball to a teammate and making late runs into the box, or by carrying the ball themselves; recent examples of this type of player are Clarence Seedorf and Bastian Schweinsteiger, while Sami Khedira and Fernandinho are destroyers with carrying tendencies.

[40] Writer Jonathan Wilson instead described Xabi Alonso's holding midfield role as that of a "creator", a player who was responsible for retaining possession in the manner of a more old-fashioned deep-lying playmaker or regista, noting that: "although capable of making tackles, [Alonso] focused on keeping the ball moving, occasionally raking long passes out to the flanks to change the angle of attack.

[42] Some attacking midfielders are called trequartista or fantasista (Italian: three-quarter specialist, i.e. a creative playmaker between the forwards and the midfield), who are usually mobile, creative and highly skilful players, known for their deft touch, technical ability, dribbling skills, vision, ability to shoot from long range, and passing prowess.

This specialist midfielder's main role is to create good shooting and goal-scoring opportunities using superior vision, control, and technical skill, by making crosses, through balls, and headed knockdowns to teammates.

[2] Where a creative attacking midfielder, i.e. an Advanced playmaker, is regularly utilised, they are commonly the team's star player, and often wear the number 10 shirt.

[47] Some examples of the advanced playmaker would be Zico, Francesco Totti, Lionel Messi, Diego Maradona, Kevin De Bruyne, Wim van Hanegem and Michel Platini.

There are also some examples of more flexible advanced playmakers, such as Zinedine Zidane, Rui Costa, Kaká, Andrés Iniesta, Juan Román Riquelme, David Silva, and Louisa Cadamuro.

These players could control the tempo of the game in deeper areas of the pitch while also being able to push forward and play line-breaking through balls.

[48][49][50][51][52] Mesut Özil can be considered as a classic 10 who adopted a slightly more direct approach and specialised in playing the final ball.

[53] Wayne Rooney has been deployed in a similar role, on occasion; seemingly positioned as a number 10 behind the main striker, he would often drop even deeper into midfield to help his team retrieve possession and start attacks.

Much like the "false 9", their specificity lies in the fact that, although they seemingly play as an attacking midfielder on paper, unlike a traditional playmaker who stays behind the striker in the centre of the pitch, the false 10's goal is to move out of position and drift wide when in possession of the ball to help both the wingers and fullbacks to overload the flanks.

When other forwards or false-9s drop deep and draw defenders away from the false-10s, creating space in the middle of the pitch, the false-10 will then also surprise defenders by exploiting this space and moving out of position once again, often undertaking offensive dribbling runs forward towards goal, or running on to passes from false-9s, which in turn enables them to create goalscoring opportunities or go for goal themselves.

In the 2−3−5 formation popular in the late 19th century wingers remained mostly near the touchlines of the pitch, and were expected to cross the ball for the team's inside and centre forwards.

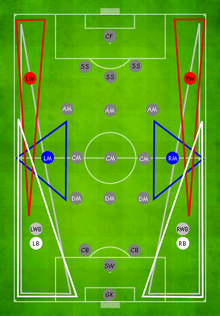

Italian manager Antonio Conte has been known to use wide midfielders or wingers who act as wing-backs in his trademark 3–5–2 and 3–4–3 formations, for example; these players are expected both to push up and provide width in attack as well as track back and assist their team defensively.

[63] Another example is Mario Mandžukić under manager Massimiliano Allegri at Juventus during the 2016–17 season; normally a striker, he was instead used on the left flank, and was required to win aerial duels, hold up the ball, and create space, as well as being tasked with pressing opposing players.

Some wingers prefer to cut infield (as opposed to staying wide) and pose a threat as playmakers by playing diagonal passes to forwards or taking a shot at goal.

Even players who are not considered quick, have been successfully fielded as wingers at club and international level for their ability to create play from the flank.

[66] As opposed to traditionally pulling the opponent's full-back out and down the flanks before crossing the ball in near the by-line, positioning a winger on the opposite side of the field allows the player to cut-in around the 18-yard box, either threading passes between defenders or shooting on goal using the dominant foot.

[69] Not only are inverted wingers able to push full-backs onto their weak sides, but they are also able to spread and force the other team to defend deeper as forwards and wing-backs route towards the goal, ultimately creating more scoring opportunities.

[74][75][76] Former Bayern Munich manager Jupp Heynckes often played the left-footed Arjen Robben on the right and the right-footed Franck Ribéry on the left.

[63][84] The "false winger" or "seven-and-a-half" is a label which has been used to describe a type of player who normally plays centrally, but who instead is deployed out wide on paper; during the course of a match, however, they will move inside and operate in the centre of the pitch to drag defenders out of position, congest the midfield and give their team a numerical advantage in this area, so that they can dominate possession in the middle of the pitch and create chances for the forwards; this position also leaves space for full-backs to make overlapping attacking runs up the flank.