Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism

Officially designated the 638th Infantry Regiment (Infanterieregiment 638), it was one of several foreign volunteer units formed in German-occupied Western Europe to participate in the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941.

After the Allied landings in Normandy and Liberation of France, the LVF was disbanded in September 1944 and its remaining personnel incorporated into the Waffen-SS in the short-lived SS "Charlemagne" Waffen-Grenadier Brigade.

[3] Critics of the country's pre-war republican regime attributed the national humiliation to the failure of parliamentary democracy and the corrupting influence of liberal individualism, communism, freemasonry and Jews.

Countering these threats were among the main organising principles of the "National Revolution" declared by the authoritarian Vichy regime under Marshal Philippe Pétain in the aftermath of the defeat.

More extreme right-wing French political factions (groupuscules) centred on Paris in the zone occupée often shared a more explicitly Nazi and pro-German ideology than Vichy.

[6] Although there had been interest within the German Foreign Ministry about closer ties with France after the defeat, these were vetoed by Adolf Hitler, who wanted total freedom to decide on the country's future after the war and was determined to keep the Vichy regime weak.

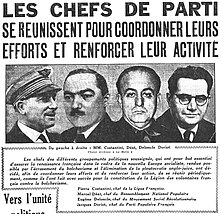

[7] The four main political factions which emerged as leading proponents of radical collaborationism in France were Marcel Déat's National Popular Rally (Rassemblement national populaire, RNP), Jacques Doriot's French Popular Party (Parti populaire français, PPF), Eugène Deloncle's Social Revolutionary Movement (Mouvement social révolutionnaire, MSR), and Pierre Costantini's French League (Ligue française).

[12] According to Jackson, "collaborationist politics was a vipers' nest of hatreds, all the more intense because power was so remote" as each vied with one another to be the single party in a future one-party state.

[11] German overtures towards these collaborationist factions put significant pressure on Vichy to renounce neutrality and gave rise to deep suspicion in Pétain's entourage.

[15] Hitler approved the unit's creation on 5 July 1941 but mandated that it be organised privately and limited to 10,000 men, much smaller than the 30,000 that Doriot and his supporters had imagined.

[16][17] At around the same time, numerous similar volunteer units were formed in other parts of German-occupied Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Norway as well as neutral Francoist Spain.

[23][24] The first large public rally for the LVF took place with German backing in the Vélodrome d'Hiver in Paris on 18 July 1941 and marked the effective start of the recruitment campaign.

Its propaganda portrayed the legion as part of a Europe-wide crusade against communism, drawing on France's medieval history and avoiding mention of Germany.

[14] The Vichy regime provided no direct support for its recruitment campaign although it partially repealed an existing law prohibiting French citizens from enlisting in foreign armed forces.

[32][17] At the same time, the German authorities blocked attempts to recruit French prisoners of war in Germany[33][34] and imposed more restrictive conditions on service in light of France's political importance within German-occupied Europe.

At the ceremonies, Pétain's deputy Pierre Laval and Déat were shot and wounded in an attempted assassination by a follower of Deloncle who had enlisted in the unit.

[45][20] The committee ultimately chose the 65-year old Colonel Roger Henri Labonne, who had no combat experience but had previously served as French military attaché in Turkey.

[46][45] The first detachment left France on 8 September 1941 and the LVF began basic training in October 1941 at Deba in the General Government, run by French-speaking German officers.

[51] The historian Oleg Beyda writes: The military training the soldiers had received was poor; little attention was paid to them, and the weapons they were given were of low quality.

Letters from home came irregularly, and the legionnaires learned soon after their arrival that their families were not receiving the whole sums stipulated in the contracts, which gave rise to general discontent.

In the aftermath of its initial deployment, the LVF was withdrawn from front-line service and assigned to so-called "bandit-fighting" operations (Bandenbekämpfung) against supposed Soviet partisans in the rear-echelons of Army Group Centre.

[39] In Radom, the Germans purged the unit of more prominent political activists as well as the White Russian, Arab and African personnel whose enlistment it had already forbidden.

[39][65] After its reorganisation, the Legion's two remaining battalions were deployed separately to "bandit-fighting" operations in the region around Smolensk under the auspices of Army Group Centre.

[67] The historian Aleksandr Vershinin states that the personnel of the LVF thought the Soviet citizens they encountered were backward, culturally inferior and even subhuman, and sometimes drew parallels with French colonial troops involved in punitive expeditions in North Africa.

[69] According to Beyda, the LVF proved to be largely ineffective in anti-partisan warfare as a result of a combination of low morale, disagreements with the German command, and military inexperience.

[77] All three battalions of the LVF were deployed as a single unit for the first time in a large-scale attack in January 1944 dubbed Operation Morocco against partisans in a large forested area near Somry in Byelorussia.

[70] As a result of its own dwindling numbers and a resurgence in partisan activity, the German military authorities had decided to withdraw the LVF to Germany on 18 June 1944 a few days before the start of the major Soviet offensive into Byelorussia.

[77][79] They were attached a Kampfgruppe hastily assembled around the 4th SS Police Regiment and fought a successful small-scale delaying action at Bobr on the Moscow-Minsk road on 26–27 June 1944 with the support of a German unit of Tiger tanks.