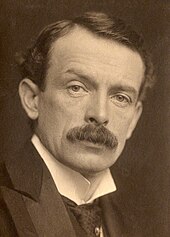

Leo Chiozza Money

[4] He was educated privately[5] and, in 1903, largely anglicised his name, appending "Money" for what Lloyd George's biographer John Grigg has described as "eponymous reasons".

These were timely given the increasingly fervent political and public debate about Imperial Preference, a cause that led Joseph Chamberlain to resign from Arthur Balfour's Conservative government in 1903.

This analysis of the distribution of wealth in the United Kingdom, which he revised in 1912, proved influential and was widely quoted by socialists, Labour politicians and trade unionists.

The future Labour Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, whose government (1945–51) established the modern welfare state, recalled that, while he was working at a boys' club at Haileybury, he had spent an evening studying Riches and Poverty.

[20] In 1912 Money was active also in following up the sinking of the RMS Titanic, soliciting from the President of the Board of Trade (Sydney Buxton) an early breakdown of the number of passengers saved by class and gender.

[21] Despite Money's apparent alignment with Lloyd George, he produced various articles early in 1914 that drew attention to reductions in naval expenditure at a time when Germany was increasing such spending.

Maclay, who was himself strong-willed and very self-disciplined,[27] at first resisted Money's appointment, describing him to Lloyd George as "very clever – but impossible, [living] in an atmosphere of suspicion and distrust of everyone – satisfied only with himself and his own views".

[29] By the time of the Zeebrugge raid in April 1918, the use of convoys had largely contained the threat from U-boats, with every troopship of American reinforcements over the previous two months having arrived safely.

He argued also that substantial investment in organisation and technology would be required to stem economic decline[31] and regretted both the coalition's lack of commitment to free trade and intention to defer Home Rule for Ireland.

Cathcart Sloley-Jones, under the illusion that he was addressing a member of parliament, "lowered his voice into a rather sinister whisper: 'What is Lloyd George's real view of the miners' report?

For example, in 1926 (the year of the General Strike), he criticised as "utterly humourless" a BBC radio play in which Father Ronald Knox offered an imaginary account of a revolution in Britain that included butchery in St. James's Park, London and the blowing up of the Houses of Parliament.

He maintained that "the European stock cannot presume to hold magnificent areas indefinitely, even while it refuses to people them, and to deny their use and cultivation to races that sorely need them".

[38] During the Second World War Money deplored British bombing of non-military targets in Germany, citing in 1943 Churchill's own denunciation of a "new and odious form of warfare" a few months before becoming Prime Minister in 1940.

[39] However, in terms of their public profile, these various activities paled into insignificance compared to two rather bizarre episodes involving young women that brought Money into contact with the law.

[44] At the time of his arrest, Money protested to the police that he was "not the usual riff-raff" but "a man of substance" and, once in custody, was permitted to telephone the Home Secretary, Sir William Joynson-Hicks.

[50] Joynson-Hicks established a public inquiry under Sir John Eldon Bankes,[51] a retired Lord Justice of Appeal, which criticised the excessive zeal of the police,[52] but also exonerated Savidge's interrogators of improper conduct.

[55] In September 1933 Money was travelling on the Southern Railway between Dorking and Ewell when, as A. J. P. Taylor put it in the relevant volume of the Oxford History of England, he "again conversed with a young lady".