Mikhail Lermontov

In another early autobiographical piece, "Povest" (The Tale), Lermontov described himself (under the guise of Sasha Arbenin) as an impressionable boy, passionately in love with all things heroic, but otherwise emotionally cold and occasionally sadistic.

Having developed a fearful and arrogant temper, he took it out on his grandmother's garden as well as on insects and small animals ("with great delight, he would squash a hapless fly and bristled with joy when a stone he'd thrown would kick a chicken off its feet").

In fact, Lermontov's poor health served in a way as a saving grace, Skabichevsky argued, for it prevented the boy from further exploring the darker sides of his character and, more importantly, "taught him to think of things... seek pleasures that he couldn't find in the outer world, deep inside himself.

While "Kavkazsky Plennik" (Caucasian Prisoner), betraying strong Pushkin influence and borrowing from the latter, "The Corsair", "Prestupnik" (The Culprit), "Oleg", "Dva Brata" (Two Brothers), as well as the original version of "The Demon" were impressive exercises in Romanticism.

[19][21] One of his fellow cadet-school students, Nikolai Martynov, the one whose fatal shot would kill the poet several years later, in his biographical "Notes" decades later described him as "the young man who was so far ahead of everybody else, as to be beyond comparison," a "real grown-up who'd read and thought and understood a lot about the human nature.

[19] Concealing his literary aspirations from friends (relatives Alexey Stolypin and Nikolai Yuriev among them), Lermontov became an expert in producing scabrous verses (like "Holiday in Petergof", "Ulansha", and "The Hospital") which were published in a school's amateur magazine Shkolnaya Zarya (School-Years' Dawn) under monikers "Count Diarbekir" and "Stepanov".

[citation needed] "Sardonic, caustic and smart, brilliantly intelligent, rich and independent, he became the soul of the high society and the leading spirit in pleasure trips and sprees," Yevdokiya Rostopchina remembered.

[22] "Extraordinary, how much youthful energy and precious time had Lermontov managed to spare upon wanton orgies and base love-making, without seriously damaging his physical and moral strength", biographer Skabichevsky marvelled.

Lermontov, who himself never belonged to the Pushkin circle (there is conflicting evidence as to whether he'd met the famous poet at all), became especially vexed with Saint Petersburg dames' sympathizing with D'Anthès, a culprit whom he even considered challenging to a duel.

The poem portrayed that society as a cabal of self-interested venomous wretches "huddling about the throne in a greedy throng", "the hangmen who kill liberty, genius, and glory" about to suffer the apocalyptic judgment of God.

Alexander von Benckendorff, a distant relative of Arsenyeva's and the founding head of the Tsar's Gendarmes and of his secret police,[19] was willing to help her grandson out but still had no choice but to report the incident to Nicholas I, who, as it turned out, had already received a copy of the poem (subtitled "The Call for the Revolution", from an anonymous sender).

Vasily Zhukovsky's letter to Minister Sergey Uvarov made possible the publication of "Pesn Kuptsa Kalashnikova" (The Song of Merchant Kalashnikov), a historical poem which the author initially sent to Krayevsky in 1837 from the Caucasus, only to be thwarted by censors.

[7] The partially autobiographical story, describing prophetically a duel like the one in which he would eventually lose his life, consisted of five closely linked tales revolving around a single character, a disenchanted, bored and doomed young nobleman.

[27] In early May 1840 Lermontov left Saint Petersburg, but arrived at Stavropol only on 10 June, having spent a whole month in Moscow, visiting (among other people) Nikolai Gogol, to whom he recited his then-new poem Mtsyri.

[7][28] After visiting Moscow (where he produced no fewer than eight poetic pieces of invective aimed at Benckendorff), on 9 May 1841, Lermontov arrived to Stavropol, introduced himself to general Grabbe and asked for permission to stay in the town.

Meanwhile, in the same salons his Cadet school friend Nikolai Martynov, dressed as a native Circassian, wore a long sword, affected the manners of a romantic hero not unlike Lermontov's Grushnitsky character.

Yekaterina failed to take her suitor seriously and in her "Notes" described him thus:At Sashenka [Vereshchagina]'s I often met her cousin, a clumsy bow-legged boy of 16 or 17, with reddened eyes, which were clever and expressive nevertheless, who had a turned-up nose and caustic sneer... Everybody was calling him just Michel and so did I, never caring about his second name.

"Mikhail, having found himself the very soul of the high society, liked to entertain himself by driving young women mad, feigning love for several days, just in order to upset matches," his friend and flatmate Alexey Stolypin wrote.

"I happened to hear several of Lermontov's victims complaining about his treacherous ways and couldn't restrict myself from openly laughing at the comic finales he used to invent for his vile Casanova feats," obviously sympathetic Yevdokiya Rostopchina recalled.

But even his love lyric, addressed to Yekaterina Sushkova or Natalya Ivanova, could not be relied upon as autobiographical; driven by fantasies, it dealt with passions greatly hypertrophied, protagonists posing high and mighty in the center of the Universe, misunderstood or ignored.

His pornographic (and occasionally sadistic) Cavalry Junkers' poems which circulated in manuscripts, marred his subsequent reputation so much so that admission of familiarity with Lermontov's poetry was not permissible for any young upper-class woman for a good part of the 19th century.

This lean period bore a few fruits: "Khadji-Abrek" (1835), his first ever published poem, and 1836's Sashka (a "darling son of Don Juan", according to Mirsky), a sparkling concoction of Romanticism, realism and what might be termed a cadet-style verse.

Eclectic Boyarin Orsha (1836), featuring a pair of conflicting heroes, driven one by blind passions, another by obligations and laws of honour, married the Byronic tradition with the elements of historical drama and folk epos.

Having read by censors as the celebration of carnal passions of the "eternal spirit of atheism", it remained banned for years (and was published for the first time in 1856 in Berlin), turning arguably the most popular unpublished Russian poem of the mid-19th century.

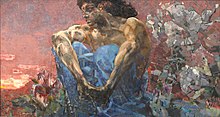

Even Mirsky, who ridiculed Demon as "the least convincing Satan in the history of the world poetry," called him "an operatic character" and fitting perfectly into the concept of Anton Rubinstein's lush opera (also banned by censors who deemed it sacrilegious) had to admit the poem had magic enough to inspire Mikhail Vrubel for his series of unforgettable images.

[5] Another 1839 poem investigating the deeper reasons for the author's metaphysical discontent with society and himself was The Novice, or Mtsyri (in Georgian), the harrowing story of a dying young monk who'd preferred dangerous freedom to protected servitude.

[15] By the late 1830s Lermontov became so disgusted with his own early infatuation with Romanticism as to ridicule it in Tambov Treasurer's Wife (1838), a close relative to Pushkin's Count Nulin, performed in stomping Yevgeny Onegin rhyme.

[15] Tellingly, while Pushkin (whose poem Tazit's plotline was here used) saw the European influence as a healthy alternative to the patriarchal ways of Caucasian natives, Lermontov tended to idealize the local communities' centuries-proven customs, their morality codex and the will to fight for freedom and independence to the bitter end.

[34] Lermontov had a peculiar method of circulating ideas, images and even passages, trying them again and again through the years in different settings until each would find itself a proper place – as if he could "see" in his imagination his future works but was "receiving" them in small fragments.

According to Lewis Bagby, "He led such a wild, romantic life, fulfilled so many of the Byronic features (individualism, isolation from high society, social critic and misfit), and lived and died so furiously, that it is difficult not to confuse these manifestations of identity with his authentic self.