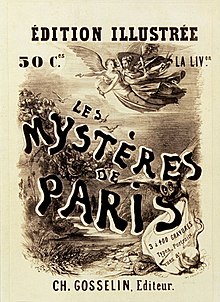

The Mysteries of Paris

Rodolphe is accompanied by his friends Sir Walter Murph, an Englishman, and David, a gifted black doctor, formerly a slave.

Though Rodolphe is described as a flawless man, Sue otherwise depicts the Parisian nobility as deaf to the misfortunes of the common people and focused on meaningless intrigues.

Rodolphe goes back to Gerolstein to take on the role to which he was destined by birth, rather than staying in Paris to help the lower classes.

Sue was the first author to bring together so many characters from different levels of society within one novel, and thus his book was popular with readers from all classes.

Its realistic descriptions of the poor and disadvantaged became a critique of social institutions, echoing the socialist position leading up to the Revolutions of 1848.

Whatever sympathy Sue created for the poor, he failed to come to terms with the true nature of the city, which had changed little.

In America, cheap pamphlet and serial fiction exposed the "mysteries and miseries" of New York, Baltimore, Boston, San Francisco and even small towns such as Lowell and Fitchburg, Massachusetts.

Dumas, at the urging of his publishers, was inspired to write The Count of Monte Cristo in part by the runaway success of The Mysteries of Paris.

He had been working on a series of newspaper articles about historical tourism in Paris and was convinced to turn them into a sensationalist melodramatic novel.

The first two translations were published in the United States in 1843, one by Charles H. Town (for Harper & Brothers) and another by Henry C. Deming (for J. Winchester's New World).