Letter of marque

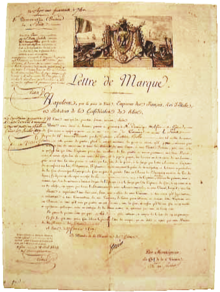

A letter of marque and reprisal (French: lettre de marque; lettre de course) was a government license in the Age of Sail that authorized a private person, known as a privateer or corsair, to attack and capture vessels of a foreign state at war with the issuer, licensing international military operations against a specified enemy as reprisal for a previous attack or injury.

A common practice among Europeans from the late Middle Ages to the 19th century, cruising for enemy prizes with a letter of marque was considered an honorable calling that combined patriotism and profit.

[4] Letters of marque allowed governments to fight their wars using mercenary private captains and sailors in place of their own navies as a measure to save time and money.

Instead of building, funding, and maintaining a navy in times of peace, governments would wait until the start of a war to issue letters of marque to privateers, who financed their own ships in expectation of prize money.

According to Grotius, letters of marque and reprisal were akin to a "private war", a concept alien to modern sensibilities but related to an age when the ocean was lawless and all merchant vessels sailed armed for self-defense.

[14] Licensing privateers during wartime became widespread in Europe by the 16th century,[15] when most countries[16] began to enact laws regulating the granting of letters of marque and reprisal.

They did not need permission to carry cannons to fend off warships, privateers, and pirates on their voyages to India and China but, the letters of marque provided that, should they have the opportunity to take a prize, they could do so without being guilty of piracy.

Similarly, on 10 November 1800, the East Indiaman Phoenix captured the French privateer General Malartic,[22] under Jean-Marie Dutertre, an action made legal by a letter of marque.

[23] During the Napoleonic Wars, the Dart and Kitty, British privateers, spent some months off the coast of Sierra Leone hunting slave-trading vessels.

For example, during the Second Barbary War (1815), President James Madison authorized the brig Grand Turk (out of Salem, Massachusetts) to cruise against "Algerine vessels, public or private, goods and effects, of or belonging to the Dey of Algiers".

[26] For this reason, enterprising maritime raiders commonly took advantage of "flag of convenience" letters of marque, shopping for cooperative governments to license and legitimize their depredations.

[27] Likewise the notorious Lafitte brothers in New Orleans cruised under letters of marque secured by bribery from corrupt officials of tenuous Central American governments, to cloak plunder with a thin veil of legality.

[28] The letter of marque by its terms required privateers to bring captured vessels and their cargoes before admiralty courts of their own or allied countries for condemnation.

A prize court's formal condemnation was required to transfer title; otherwise the vessel's previous owners might well reclaim her on her next voyage, and seek damages for the confiscated cargo.

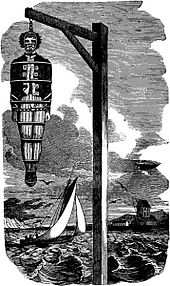

[31][32] Privateers were also required by the terms of their letters of marque to obey the laws of war, honour treaty obligations (avoid attacking neutrals), and in particular to treat captives as courteously and kindly as they safely could.

[35] Benjamin Franklin had attempted to persuade the French to lead by example and stop issuing letters of marque to their corsairs, but the effort foundered when war loomed with Britain once again.

[36] The French Convention did forbid the practice, but it was reinstated after the Thermidorian Reaction, in August 1795; on 26 September 1797, the Ministry of the Navy was authorized to sell small ships to private parties for this purpose.

In December 1941 and the first months of 1942, Goodyear commercial L-class blimp Resolute operating out of Moffett Field in Sunnyvale, California, flew anti-submarine patrols.

The United States has not legally commissioned any privateers since 1815, although the status of submarine-hunting Goodyear airships in the early days of World War II created significant confusion.