Letter of credit

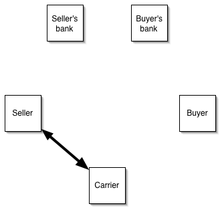

Letters of credit are used extensively in the financing of international trade, when the reliability of contracting parties cannot be readily and easily determined.

Its economic effect is to introduce a bank as an underwriter that assumes the counterparty risk of the buyer paying the seller for goods.

At this point, the nominated bank will inform the beneficiary of the discrepancy and offer a number of options depending on the circumstances after consent of applicant.

The International Chamber of Commerce oversaw the preparation of the first Uniform Customs and Practice for Documentary Credits (UCP) in 1933, creating a voluntary framework for commercial banks to apply to transactions worldwide.

[7] Beginning in 1973 with the creation of SWIFT, banks began to migrate to electronic data interchange as a means of controlling costs, and in 1983 the UCP was amended to allow "teletransmission" of letters of credit.

[7] Marcell David Reich (commonly known as Marc Rich) popularised the use of letters of credit in the oil trade.

However, if a document other than the invoice must be issued in a way to show the applicant's name, in such a case that requirement must indicate that in the transferred credit it will be free.

Outlined in the UCP 600, the bank will give an undertaking (or promise), on behalf of buyer (who is often the applicant) to pay the beneficiary the value of the goods shipped if acceptable documents are submitted and if the stipulated terms and conditions are strictly complied with.

The buyer can be confident that the goods he is expecting only will be received since it will be evidenced in the form of certain documents, meeting the specified terms and conditions.

The supplier finds his confidence in the fact that if such stipulations are met, he will receive payment from the issuing bank, who is independent of the parties to the contract.

Letters of Credit are often used in international transactions to ensure that payment will be received where the buyer and seller may not know each other and are operating in different countries.

[19] Some of the other risks inherent in international trade include: The payment will be obtained for nonexistent or worthless merchandise against presentation by the beneficiary of forged or falsified documents.

Alternatively, performance of a contract – including an obligation under a documentary credit relationship – could also be prevented by external factors such as natural disasters or armed conflicts.

Secondly, the bank will be exposed to a risk of fraud by the seller, who may provide incorrect or falsified documents to receive payment.

While he may be sued by the applicant at a later point, the issuing bank cannot reduce the payment owed to correspond with the damage occurred.

As is a core tenet of financial law, market practice comprises a substantial portion of how parties behave.

Accordingly, if the documents tendered by the beneficiary or their agent are in order, then, in general, the bank is obliged to pay without further qualifications.

The whole commercial purpose for which the system of confirmed irrevocable documentary credits has been developed in international trade is to give to the seller an assured right to be paid before he parts with control of the goods under sale.

It further does not permit of any dispute with the buyer as to the performance of the contract of sale being used as a ground for non-payment or reduction or deferment of payment.

This would place the risk on the buyer, but it also means that the issuing bank must be stringent in assessing whether the presenting documents are legitimate.

Since the basic function of the credit is to provide a seller with the certainty of payment for documentary duties, it would seem necessary that banks should honor their obligation in spite of any buyer allegations of misfeasance.

[22] If this were not the case, financial institutions would be much less inclined to issue documentary credits because of the risk, inconvenience, and expense involved in determining the underlying goods.

[3][23] The general legal maxim de minimis non curat lex (literally "The law does not concern itself with trifles") has no place in the field.

Legal writers have failed to satisfactorily reconcile the bank's obligation to pay on behalf of the applicant with any contractually-founded, academic analysis.

Some theorists suggest that the obligation to pay arises through the implied promise, assignment, novation, reliance, agency, estoppel and even trust and the guarantees.

[26] It might also be feasible to typify letters of credit as a collateral contract for a third-party beneficiary, because three different entities participate in the transaction: the seller, the buyer, and the banker.

As a result, this kind of arrangement would make letter of credit to be enforceable under the action assumpsit because of its promissory connotation.

Courts eventually dealt with the device by treating it as a hybrid of a mandate (Auftrag) and authorization-to-pay contract (Anweisung).

[28] Letters of credit came into general domestic use in the United States during World War I, although they had been used in American foreign trade for some time prior.

[5] Article 5 of the Uniform Commercial Code, drafted in 1952, provided a basis for codifying many UCP principles into state law[5] and created one of the only extensive specific legal regulations of letters of credit worldwide, although the UCC rules do not cover all aspects of letters of credit.