Li Shizeng

After coming to Paris in 1902, Li took a graduate degree in chemistry and biology, and then along with Wu Zhihui and Zhang Renjie, cofounded the Chinese anarchist movement.

There he met Zhang Renjie, the son of a prosperous Zhejiang silk merchant whose family had purchased him a degree and who had come to the capital to arrange a suitable office.

When Li was chosen in 1903 as an "embassy student" to accompany China's new ambassador Sun Baoqi to Paris, Zhang had his family arrange for him to join the group as a commercial attache.

On route back to China for a visit, Zhang met the anti-Manchu revolutionary, Sun Yat-sen and promised him extensive financial support.

[8] The Paris anarchists argued that China needed to abolish Confucian family structure, liberate women, promote moral personal behavior, and create equitable social organizations.

In later years, before moving to Taiwan in 1949, the Society became a powerful financial conglomerate, but in its early phase focused on programs of education and radical change.

[12] In 1908, the World Society started a weekly journal, Xin Shiji 新世紀週報 (New Era or New Century; titled La Novaj Tempoj in Esperanto), to introduce Chinese students in France, Japan, and China to the history of European radicalism.

[13] Li eagerly read and translated essays by William Godwin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Élisée Reclus, and the anarchist classics of Peter Kropotkin, especially The Conquest of Bread and Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution.

[13] Li was also impressed by conversations with the Kropotkinist writer Jean Grave, who had spent two years in prison for publishing "Society on the Brink of Death" (1892) an anarchist pamphlet.

Li wrote in 1907 that The Paris group worked on the assumption that science and rationality would lead toward a world civilization in which China would participate on an equal basis.

[16] By 1910, Zhang Renjie, who continued to travel back and forth to China to promote business and support revolution, could no longer finance both Sun Yat-sen and the journal, which ceased publication after 121 issues.

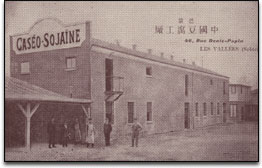

[17][18] The plant, housed in a brick building at 46–48 Rue Denis Papin in the suburb of La Garenne-Colombes a few miles to the north of Paris, produced a variety of soy products.

[20] Li planned the Work-Study program as a way to bring young Chinese to France whose study would be financed by working in the beancurd factory and whose character would be uplifted by a regimen of moral instruction.

[24][25] Together with his partner L. Grandvoinnet, in 1912 Li published a 150-page pamphlet containing their series of eight earlier articles: Le soja: sa culture, ses usages alimentaires, thérapeutiques, agricoles et industriels (Soya – Its Cultivation, Dietary, Therapeutic, Agricultural and Industrial Uses; Paris: A Challamel, 1912).

The soy historians William Shurtleff and Akiko Aoyagi call it "one of the earliest, most important, influential, creative, interesting, and carefully researched books ever written about soybeans and soyfoods.

[20] On the eve of the Xinhai revolution, Li joined Zhang Renjie in Beijing (they may have taken part in a plot to assassinate Yuan Shikai, who had edged out Sun Yat-sen from the presidency of the new republic).

These moral principles had a wide appeal among the new intelligentsia which was forming in cities and universities, but Li, in light of the Society's prohibition on holding office, turned down Sun Yat-sen's request that he join the new government, as did Wang Jingwei.

In addition to making workers more knowledgeable, work-study would eliminate their "decadent habits" and transform them into morally upright and hard-working citizens [30] Yuan Shikai's opposition closed the program down.

By March 1916 their Paris group, the Societe Franco-Chinoise d'Education (華法教育會 Hua-Fa jiaoyuhui) was directly involved in recruiting and training these workers.

They pressed the French government to give the workers technical education as well as factory work, and Li wrote extensively in the Chinese Labor Journal (Huagong zazhi), which introduced Western science, the arts, fiction, and current events.

He went on to make clear that as a cosmopolitan he did not oppose Christianity because it was foreign, but all religion as such: The former Paris Anarchists became a force in Sun Yat-sen's Nationalist Party as it rose to national power in the early 1920s.

In 1927, Li and Wu Zhihui were appointed as Chairmen of the Party, Cai Yuanpei accepted a series of offices in the new government, and Zhang Renjie was one of the powers behind Chiang's takeover after Sun's death.

Many of these young anarchists did so but others sharply pointed out that Li had originally made the renunciation of political office a key principle; the defining goal of anarchism was to overthrow the state not join it.

When the Palace Museum was set up to oversee the vast art collections left by the emperors, Li was appointed Director General, and his protégé and distant relative Yi Peiji was made curator.

By the mid-1920s, many intellectuals and nationalists had come to recognize and strongly oppose the depredation of China's artistic heritage and the export of art by Chinese and foreign dealers.

[41] In 1927, following bloody suppression of the communists and the left in April, Li gained preliminary support for a National Labor University (Laodong Daxue) in Shanghai.

Two factories had been set up by the Shanghai municipal government several years earlier, one for juvenile delinquents and homeless youth and another to provide jobs for the urban poor, but they had been shut down when the Chiang's troops took the city, leaving six-hundred young workers with no work.

Li and Cai had been impressed with the rational organization of the French system of higher education in which, instead of random groupings, the country was divided into regional districts which did not overlap or duplicate each other's missions.

To pay for ambitious cataloging and publication projects Yi had sold off gold dust, silver, silk, and clothing without government approval.

As communist armies approached Beijing in 1948, Li moved to Geneva, where he and his wife remained until 1950, when Switzerland extended recognition to the People's Republic.