Liang Qichao

Liang's father, Liang Baoying (梁寶瑛, Cantonese: Lèuhng Bóu-yīng; courtesy name Lianjian 蓮澗; Cantonese: Lìhn-gaan), was a farmer and local scholar, but had a classical background that emphasized on tradition and education for ethnic rejuvenescence allowed him to be introduced to various literary works at six years old.

Inspired by the book Illustrated Treatise on the Maritime Kingdoms by the reform Confucian scholar Wei Yuan, Liang became extremely interested in western political thought.

After returning home, Liang went on to study with Kang Youwei, who was teaching at Wanmu Caotang [zh] in Guangzhou.

[3]: 129 After failing to pass the examination for a second time, he stayed in Beijing to help Kang publish Domestic and Foreign Information.

He organized reforms with Kang Youwei[3]: 129 by putting their ideas on paper and sending them to the Guangxu Emperor (reigned 1875–1908) of the Qing dynasty.

[3]: 129 Their proposal asserted that China was in need of more than self-strengthening, and called for many institutional and ideological changes such as getting rid of corruption and remodeling the state examination system.

[4] This proposal soon ignited a frenzy of disagreement, and Liang became a wanted man by order of Empress Dowager Cixi, the leader of the political conservative faction who later took over the government as regent.

In Japan, he continued to actively advocate the democratic cause by using his writings to raise support for the reformers’ cause among overseas Chinese and foreign governments.

During his time in Japan, Liang also served as a benefactor and colleague to Phan Boi Chau, one of Vietnam's most important anticolonial revolutionaries.

In 1900–1901, Liang visited Australia on a six-month tour that aimed at raising support for a campaign to reform the Chinese empire and thus modernize China through adopting the best of Western technology, industry and government systems.

In 1903, Liang embarked on an eight-month lecture tour throughout the United States, which included a meeting with President Theodore Roosevelt in Washington, DC, before returning to Japan via Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

[7]: 32 The descendant of Confucius Duke Yansheng was proposed as a replacement for the Qing dynasty as Emperor by Liang Qichao.

Liang favored nationalism that incorporated different ethnic groups of the Qing empire to oppose Western imperialists.

Liang, as a historian and a journalist, believed that both careers must have the same purpose and "moral commitment," as he proclaimed, "by examining the past and revealing the future, I will show the path of progress to the people of the nation."

Thus, he founded his first newspaper, called the Qing Yi Bao (淸議報), named after a student movement of the Han dynasty.

Liang produced a widely read biweekly journal called New Citizen (Xinmin Congbao 新民叢報), first published in Yokohama, Japan on February 8, 1902.

The journal covered many different topics, including politics, religion, law, economics, business, geography and current and international affairs.

Undoubtedly, his attempt to unify and dominate a fast-growing and highly competitive press market has set the tone for the first generation of newspaper historians of the May Fourth Movement.

For example, Liang wrote a well known essay during his most radical period titled "The Young China" and published it in his newspaper Qing Yi Bao (淸議報) on February 2, 1900.

Weak press: However, Liang thought that the press in China at that time was quite weak, not only due to lack of financial resources and to conventional social prejudices, but also because "the social atmosphere was not free enough to encourage more readers and there was a lack of roads and highways that made it hard to distribute newspapers".

Liang Qichao contributed to the reform in late Qing by writing various articles interpreting non-Chinese ideas of history and government, with the intent of stimulating Chinese citizens' minds to build a new China.

Liang shaped the ideas of democracy in China, using his writings as a medium to combine Western scientific methods with traditional Chinese historical studies.

He advocated the Great Man theory in his 1899 piece, "Heroes and the Times" (英雄與時勢, Yīngxióng yǔ Shíshì), and he also wrote biographies of European state-builders such as Otto von Bismarck, Horatio Nelson, Oliver Cromwell, Lajos Kossuth, Giuseppe Mazzini, and Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour; as well as Chinese men including Zheng He, Tan Sitong, and Wang Anshi.

[12][13] During this period of Japan's challenge in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), Liang was involved in protests in Beijing pushing for an increased participation in the governance by the Chinese people.

This changing outlook on tradition was shown in the historiographical revolution (史學革命) launched by Liang Qichao in the early twentieth century.

[13] The article also attacked old historiographical methods, which he lamented focused on dynasty over state; the individual over the group; the past but not the present; and facts, rather than ideals.

His essays were published in a number of journals, drawing interest among Chinese intellectuals who had been taken aback by the dismemberment of China's formidable empire at the hands of foreign powers.

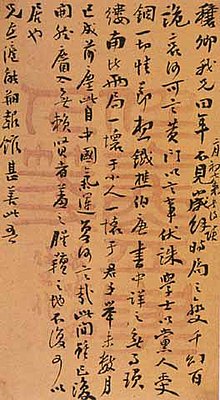

It states that "Every morning, I receive the mandate [for action], every evening I drink the ice [of disillusion], but I remain ardent in my inner mind" (吾朝受命而夕飲冰,我其內熱與).

He founded the Jiangxue she (Chinese Lecture Association) and brought important intellectual figures to China, including Driesch and Rabindranath Tagore.

Academically he was a renowned scholar of his time, introducing Western learning and ideology, and making extensive studies of ancient Chinese culture.