Liberalism in the United Kingdom

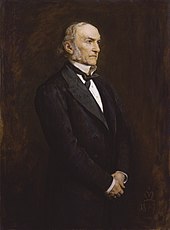

The historian H. C. G. Matthew states that Gladstone's chief legacy lay in three areas: his financial policy; his support for Home Rule (devolution) that modified the view of the unitary state of Great Britain; and his idea of a progressive, reforming party broadly based and capable of accommodating and conciliating varying interests, along with his speeches at mass public meetings.

[4] Historian Walter L. Arnstein concludes "Notable as the Gladstonian reforms had been, they had almost all remained within the nineteenth-century Liberal tradition of gradually removing the religious, economic, and political barriers that prevented men of varied creeds and classes from exercising their individual talents in order to improve themselves and their society.

As the third quarter of the century drew to a close, the essential bastions of Victorianism still held firm: respectability; a government of aristocrats and gentlemen now influenced not only by middle-class merchants and manufacturers but also by industrious working people; a prosperity that seemed to rest largely on the tenets of laissez-faire economics; and a Britannia that ruled the waves and many a dominion beyond.

The reformers' leaders were Thomas Hill Green and Herbert Samuel, that in the Progressive Review of December 1896, said that the classical liberalism was "sapped and raddled", claiming for more state's powers.

[14] Samuel's "New Liberalism" called for old-age pensions, labour exchanges (job-placement organizations), and workers' compensation, all prefiguring modern welfare.

Other important intellectuals 1906-14 included H. A. L. Fisher, Gilbert Murray, G. M. Trevelyan, Edwin Montagu, Charles Masterman, Alfred Marshall, Arthur Cecil Pigou and young John Maynard Keynes.

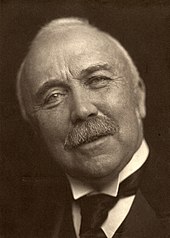

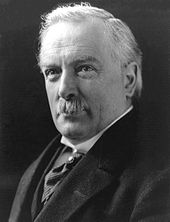

[16] Key politicians included future prime ministers Henry Campbell-Bannerman, Winston Churchill,[17] H. H. Asquith and David Lloyd George, sceptics of non-interventionism on economy and free market, embraced the New Liberalism.

[18][19] To fund extensive welfare reforms Lloyd George proposed taxes on land ownership and high incomes in the "People's Budget" (1909), which the Conservative-dominated House of Lords rejected.

The government could force the unwilling king to create new Liberal peers, and that threat did prove decisive in the battle for dominance of Commons over Lords in 1911.

[21] The report, in shortened terms, aimed to bring widespread reform to the United Kingdom and did so by identifying the "five giants on the road of reconstruction": "Want… Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness".

The post-war consensus included a belief in Keynesian economics,[21] a mixed economy with the nationalisation of major industries, the establishment of the National Health Service and the creation of the modern welfare state in Britain.

[23] With the rise of Margaret Thatcher as Conservative Party leader in the 1975 leadership election ushered in a resurgence of the old 19th-century Gladstone laissez-faire Classical liberal principles.

[25] This philosophy became known as Thatcherism and it focused on rejecting the post-war consensus that tolerated or encouraged nationalisation, strong labour unions, heavy regulation, high taxes, and a generous welfare state.

She held the belief that the existing trend of unions was bringing economic progress to a standstill by enforcing "wildcat" strikes, keeping wages artificially high and forcing unprofitable industries to stay open.

Thatcherism promoted low inflation, the small state, and free markets through tight control of the money supply, privatisation and constraints on the labour movement.

It is a key part of the worldwide Classical liberal movement and as such is often compared with Reaganomics in the United States, Economic Rationalism in Australia and Rogernomics in New Zealand.