Asser

Doubts have also been raised periodically about whether the entire Life is a forgery, written by a slightly later writer, but it is now almost universally accepted as genuine.

[2] According to his Life of King Alfred, Asser was a monk at St David's in what was then the kingdom of Dyfed, in south-west Wales.

Alfred held a high opinion of the value of learning and recruited men from around Britain and from continental Europe to establish a scholarly centre at his court.

Several kings, including Hywel ap Rhys of Glywysing and Hyfaidd of Dyfed (where Asser's monastery was), had submitted to Alfred's overlordship in 885.

[3] Asser provides only one datable event in his history: on St Martin's Day, 11 November 887, Alfred decided to learn to read Latin.

[2] Asser's response to Alfred's request was to ask for time to consider the offer, as he felt it would be unfair to abandon his current position in favour of worldly recognition.

On his return to Wales, however, Asser fell ill with a fever and was confined to the monastery of Caerwent for twelve months and a week.

Asser gives no information about his time in Wales, but mentions various places that he visited in England, including the battlefield at Ashdown, Cynuit (Countisbury), and Athelney.

It is also clear from the text that Asser was familiar with Virgil's Aeneid, Caelius Sedulius's Carmen Paschale, Aldhelm's De Virginitate, and Einhard's Vita Karoli Magni ("Life of Charlemagne").

He quotes from Gregory the Great's Regula Pastoralis, a work he and Alfred subsequently collaborated in translating, and from Augustine of Hippo's Enchiridion.

Asser also adds material relating to the years after 887 and general opinions about Alfred's character and reign.

[2][10] Asser's prose style has been criticised for weak syntax, stylistic pretensions, and garbled exposition.

His frequent use of archaic and unusual words gives his prose a baroque flavour that is common in Insular Latin authors of the period.

This has led to speculation that he was educated at least partly in Francia, but it is also possible that he acquired this vocabulary from Frankish scholars he associated with at court, such as Grimbald.

Asser takes pains to explain local geography, so he was clearly considering an audience not familiar with the areas he described.

There are also sections such as the support for Alfred's programme of fortification that give the impression of the book's being aimed at an English audience.

Asser describes her as behaving "like a tyrant" and ultimately accidentally poisoning Beorhtric in an attempt to murder someone else.

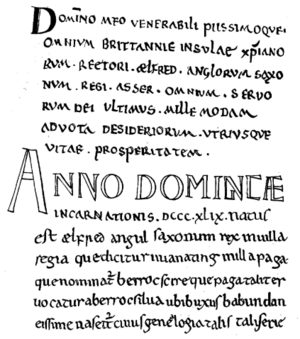

There is some evidence from early writers of access to versions of Asser's work, as follows:[17] The history of the Cotton manuscript itself is quite complex.

Although Parker bequeathed most of his library to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, the Cotton manuscript was not included.

In addition to these transcripts, the extracts mentioned above made by other early writers have been used to help assemble and assess the text.

Because of the lack of the manuscript itself and because Parker's annotations had been copied by some transcribers as if they were part of the text, scholarly editions have had a difficult burden.

[21] In 1603 the antiquarian William Camden published an edition of Asser's Life in which there appears a story of a community of scholars at Oxford, who were visited by Grimbald: In the year of our Lord 886, the second year of the arrival of St Grimbald in England, the University of Oxford was begun ... John, monk of the church of St David, giving lectures in logic, music and arithmetic; and John, the monk, colleague of St Grimbald, a man of great parts and a universal scholar, teaching geometry and astronomy before the most glorious and invincible King Alfred.

[2][26] The title "king of the Anglo-Saxons" does, however, in fact occur in royal charters that date to before 892 and "parochia" does not necessarily mean "diocese", but can sometimes refer just to the jurisdiction of a church or monastery.

Aside from the fact that Leofric would have known little about Asser and so would have been unlikely to construct a plausible forgery, there is strong evidence dating the Cotton manuscript to about 1000.

Galbraith's arguments were refuted to the satisfaction of most historians by Dorothy Whitelock in Genuine Asser, in the Stenton Lecture of 1967.

Byrhtferth's motive, according to Smyth, is to lend Alfred's prestige to the Benedictine monastic reform movement of the late tenth century.

The historian William of Malmesbury, writing in the 12th century, believed that Asser also assisted Alfred with his translation of Boethius.