Lincoln Arcade

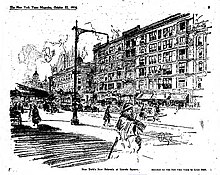

Built in 1903, it was viewed by contemporaries as a sign of the northward extension of business-oriented real estate ventures, and the shops, offices, and other enterprises.

One observer styled some of these newcomers as "starving students, musicians, actors, dead-beat journalists, nondescript authors, tarts, polite swindlers, and fugitives from injustice.

Most of these men and women received little attention from the public either during their lives or since their deaths, but some, such as George Bellows, Thomas Hart Benton, Stuart Davis, Marcel Duchamp, Eugene O'Neill, and Lionel Barrymore, became famous.

In the late 1700s the western part of Manhattan where the building would be constructed was known as Bloemendaal or Blooming Dale, the valley of flowers, where could be found large farms.

[2] In the early 1800s the city expanded its street network north to the district and the farms that originally dominated the area were broken up into lots that were held as investments.

[2] Through inheritance, the location where the Lincoln Arcade would later be built was transferred from the original farm owner, John Somerindyke, to the widow of one of his sons, Abigail Thorn, in 1809.

Near the corner of West 66th Street and the Boulevard there was another two-story warehouse, a coal yard, and, outside the area where the Lincoln Arcade would be erected, a five-story commercial building.

[21] As construction neared completion, a news piece cited it as the keystone of developers' hopes for business-oriented real estate in the vicinity (an area they were now calling "Empire Square").

[31] By 1918, what was then called the "Lincoln Square District" was said to be unusually profitable for real estate investors, appearing to possess "the qualities for greater building achievements in the years rapidly approaching than those just forgotten.

"[32] Miller sought to fill the Arcade with tenants by placing small ads in the local press and in journals such as the Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide.

[25] One drew attention to the building's "Most Remarkable Location" with its "Car line and subway and 'L' stations exceeding any point in the city" where could be found "studios, offices and floors, $15 to $100 [with] elevators, steam heat, gas, electricity, baths.

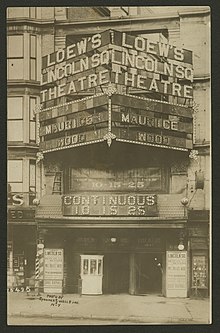

In the novel, Johnson wrote that the Arcade stood, "at that intersection of Broadway and Columbus Avenue, where the grumbling subway and the roaring elevated meet at Lincoln Square."

He continued, "It covered a block, bisected by an arcade and rising six capacious stories in the form of an enormous H. On Broadway, the glass front was given over to shops and offices of all descriptions, while in the back stretches of the top stories, artists, sculptors, students, and illustrators had their studios alongside of mediums, dentists, curious business offices, and derelicts of all description."

)[37] Among street-level tenants during the building's early years were a candy store, a barber, a clock maker, a milliner's shop, a billiard parlor, and two corner saloons.

[40] The upper floors contained stenographers, dance instructors, lawyers, dentists, health faddists, fortune tellers, a school of Jiu-Jitsu, and detective agencies.

[39][41] Although it listed studios, along with offices and stores, as a feature of the building, management did not market the Arcade to artists and other creative arts individuals.

During its early years, in addition to its many artists, it contained the opera star, Rosa Ponselle, the puppeteers, Sue Hastings, Edwin Deaves, and Garrett Becker, the movie director, Rex Ingram, and writers such as William Huntington Wright (S. S. Van Dine) and Thomas Craven.

[43] He wrote, "The Arcade housed an unsavory crew: commercial artists, illustrators, starving students, musicians, actors, dead-beat journalists, nondescript authors, tarts, polite swindlers, and fugitives from injustice.

"[1]: 250 In his life of John Sloan, Van Wyck Brooks said the building was a "rookery of half-fed students, astrologers, prostitutes, actors, models, prize-fighters, quacks and dancers.

[50] Others, mostly men, fared better in the art world: Robert Henri, George Bellows, Milton Avery, Marcel Duchamp, Thomas Hart Benton, Stuart Davis, Alexander Archipenko, and Raphael Soyer to name a few.

One of the more successful tenants later recalled that the building had the reputation of being a good luck spot for budding artists, adding that "many of the great ones had started up the ladder there.

"[56] Artists who arrived between 1911 and 1915 included Glenn Coleman, Henry Glittenkamp, Stuart Davis, Thomas Hart Benton, Raeburn Van Buren, Ralph Barton,: 133 and Neysa McMein.

[61] Tenants during the 1920s and until the building was demolished included Morris Kantor, Raphael Soyer, Reginald Marsh, Milton Avery, and Alexander Archipenko.

[note 17] In 1934 Miller's mortgage holder, City Bank of New York, foreclosed the property and, failing to find a buyer, hired a service company to manage it.

When, in the late 1940s, a slum-clearance initiative targeted the area around Lincoln Square, it was at first unclear whether the Arcade would be included in the scheme and it was not until 1958 that the decision was made to raze the building to make way for the new home of the Juilliard School.