Lindow Man

Dating the body has proven problematic, but it is thought that he was deposited into Lindow Moss, face down, sometime between 2 BC and 119 AD, in either the Iron Age or Romano-British period.

At the time of death, Lindow Man was a healthy male in his mid-20s, and may have been of high social status as his body shows little evidence of having done heavy or rough physical labour during his lifetime.

[1] Sphagnum moss affects the chemistry of nearby water, which becomes highly acidic (a pH of roughly 3.3 to 4.5) relative to a more ordinary environment.

[10] While in prison on another charge, her husband, Peter Reyn-Bardt, had boasted that he had killed his wife and buried her in the back garden of their bungalow, which was on the edge of the area of mossland where peat was being dug.

On 1 August 1984, Andy Mould, who had been involved in the discovery of Lindow Woman, took what he thought was a piece of wood off the elevator of the peat-shredding machine.

[5] Rick Turner, the Cheshire County Archaeologist, was notified of the discovery and succeeded in finding the rest of the body,[12] which later became known as Lindow Man.

[9] The owners of the land where Lindow Man was found donated the body to the British Museum, and on 21 August it was transported to London.

[17] As the best-preserved bog body found in Britain, its discovery caused a domestic media sensation and received global coverage.

Encouraged by the discovery of Lindow Man, a gazetteer was compiled, which revealed a far higher number of bog bodies: over 85 in England and Wales and over 36 in Scotland.

The interest caused by Lindow Man led to more in-depth research of accounts of discoveries in bogs since the 17th century; by 1995, the numbers had changed to 106 in England and Wales and 34 in Scotland.

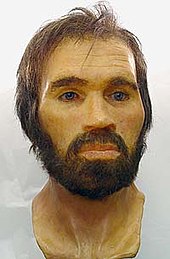

The body retains a trimmed beard, moustache, and sideburns of brown hair, as well as healthy teeth with no visible cavities, and manicured fingernails, indicating he did little heavy or rough work.

It was found that the copper content of the skin of the torso was higher than the control areas, suggesting that the theory of Pyatt et al. may have been correct.

[34][35] There has been a tendency to ascribe the body to the Iron Age period rather than Roman due to the interpretation that Lindow Man's death may have been a ritual sacrifice or execution.

Archaeologist P. C. Buckland suggests that as the stratigraphy of the peat appears undisturbed, Lindow Man may have been deposited into a pool that was already some 300 years old.

[36] Geographer K. E. Barber has argued against this hypothesis, saying that pools at Lindow Moss would have been too shallow, and suggests that the peat may have been peeled back to allow the burial and then replaced, leaving the stratigraphy apparently undisturbed.

[43] According to Jody Joy, curator of the Iron Age collection at the British Museum,[44] the importance of Lindow Man lies more in how he lived rather than how he died, as the circumstances surrounding his demise may never be fully established.

However, Robert Connolly, a lecturer in physical anthropology, suggests that the sinew may have been ornamental and that ligature marks may have been caused by the body swelling when submerged.

[51] Archaeologist Don Brothwell considered that many of the older bodies need re-examining with modern techniques, such as those used in the analysis of Lindow Man.

The study of bog bodies, including those found in Lindow Moss, has contributed to a wider understanding of well-preserved human remains, helping to develop new methods of analysis and investigation.

[56] In the latter half of the 20th century, scholars widely believed that bog bodies demonstrating injuries to the neck or head area were examples of ritual sacrifice.

[57] According to Brothwell, Lindow Man is one of the most complex examples of "overkill" in a bog body, and possibly has ritual meaning as it was "extravagant" for a straightforward murder.

[58] Archaeologists John Hodgson and Mark Brennand suggest that bog bodies may have been related to religious practice, although there is division in the academic community over this issue.

[16][50] Joy said The jury really is still out on these bodies, whether they were aristocrats, priests, criminals, outsiders, whether they went willingly to their deaths or whether they were executed – but Lindow was a very remote place in those days, an unlikely place for an ambush or a murder[45]According to Anne Ross, a scholar of Celtic history and Don Robins, a chemist at the University of London, Lindow Man was likely a sacrifice victim of extraordinary importance.

They identified his stomach contents as including the undigested remains of a partially burned barley griddle cake of a kind used by the ancient Celts to select victims for sacrifice.

They argued that Lindow Man was likely a high-ranking Druid who was sacrificed in a last-ditch effort to call upon the aid of three Celtic gods to stop a Roman offensive against the Celts in AD 60.

After rejecting methods that had been used to maintain the integrity of other bog bodies, such as the "pit-tanning" used on Grauballe Man, which took a year and a half, scientists settled on freeze-drying.

Afterwards, Lindow Man was put in a specially constructed display case to control the environment, maintaining the temperature at 20 °C (68 °F) and the humidity at 55%.

[68] Critics have complained that, by museum display of the remains, the body of Lindow Man has been objectified rather than treated with the respect due to the dead.

This is part of a wider discussion about the scientific treatment of human remains and museum researchers and archaeologists using them as information sources.

[70] Celtic history, language and lore scholar Anne Ross and archaeological chemist Don Robins's The Life and Death of a Druid Prince provides an account of the circumstances surrounding Lindow Man's life and death, in part hypothesising that he had lived as a highborn, perhaps even as a druid who was sacrificed to the gods at the time of the Menai Massacre and Boudica's rebellion.