Line of battle

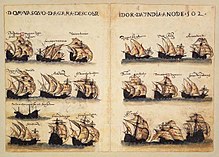

The first recorded mention of the use of a line of battle tactic is to be found in the Instructions, provided in 1500 by Manuel I, king of Portugal, to the commander of a fleet dispatched to the Indian Ocean.

Portuguese fleets overseas deployed in line ahead, firing one broadside and then putting about in order to return and discharge the other, resolving battles by gunnery alone.

[2] Line-of-battle tactics had been used by the Fourth Portuguese India Armada at the Battle of Calicut (1503), under Vasco da Gama, near Malabar against a Muslim fleet.

[3] One of the earliest recorded deliberate uses is documented in the First Battle of Cannanore between the Third Portuguese India Armada under João da Nova and the naval forces of Calicut, earlier in the same year.

Albuquerque made his small fleet (but powerful in its artillery) circle like a carrousel, but in a line end-to-end, and destroyed most of the ships that surrounded his squadron.

[citation needed] From the mid-16th century, the cannon gradually became the most important weapon in naval warfare, replacing boarding actions as the decisive factor in combat.

At the same time, the natural tendency in the design of galleons was for longer ships with lower forecastles and aftercastles, which meant faster, more stable vessels.

These newer warships could mount more cannons along the sides of their decks, concentrating their firepower along their broadside, while presenting a lower target to their enemy.

[citation needed] Until the mid-17th century, the tactics of a fleet were often to "charge" the enemy, firing bow chaser cannon, which did not deploy the broadside to its best effect.

After Tromp refused to strike sail in salute, a battle took place, but the Dutch, despite their superior numbers, failed to capture any English ships.

[7] The Battle of the Kentish Knock (28 September 1652) revealed the weakness of the Dutch fleet, largely consisting of smaller ships, against the English.

[14] The line-of-battle tactic favoured very large ships that could sail steadily and maintain their place in the line in the face of heavy fire.

The change toward the line of battle also depended on an increased disciplining of society and the demands of powerful centralized government to keep permanent fleets led by a corps of professional officers.

The French in particular were adept at gunnery and would generally take the leeward position to enable their fleet to retire downwind while continuing to fire chain-shot at long range to bring down masts.

[17] In the years following the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, the British Admiralty carried out a radical reform of ship design – between 1810 and 1840, every detail was altered, and more advances occurred during this period than had happened since the 1660s.