Linnaean Herbarium

The herbarium includes specimens from Linnaeus's botanical explorations and global collaborations, spanning early Swedish collections to acquisitions from the Americas, Asia, and Africa.

The Linnaean Herbarium remains a key resource for botanical research and understanding 18th-century scientific practices, with ongoing preservation, documentation, and digitisation efforts improving its accessibility.

Current research, including the Linnaean Plant Name Typification Project, demonstrates its enduring relevance in botanical studies more than two centuries after its creation.

[1] The collection grew significantly during his time in Holland and England (1735–38), where he acquired specimens from Virginia, the West Indies, Central America, and various gardens.

[1] This period was vital for his botanical development, as he obtained specimens from diverse sources, including George Clifford's garden and John Clayton's Virginian collection (via Johann Gronovius).

[2] Linnaeus avidly collected specimens during his 1732 Lapland journey (where he named Linnaea borealis) and trips to Öland, Gotland, and Skåne.

[3] By 1753, when Linnaeus published Species Plantarum, the herbarium included specimens from southern France, other parts of Europe, Siberia, coastal China, India, southeastern Canada, New York, and Pennsylvania.

[6] In December 1783, Sara Elisabeth Moræa, Linnaeus's widow, offered to sell his collection to Sir Joseph Banks for 1000 guineas.

The acquisition of the collection marked a significant moment in natural history, as it provided the material and social basis for the advancement of the Linnaean system in Britain.

Smith founded the Linnean Society of London in 1788, initially meeting at his residence where the collections were housed in their original storage cabinets.

The Society bought it from the executors of Sir James Edward Smith (1759–1828) to make its contents permanently available to botanical scholars.

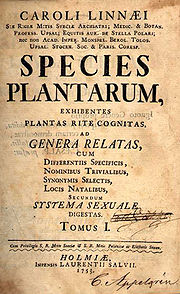

[1] The Linnaean Herbarium is fundamental to modern botanical nomenclature, as Linnaeus's 1753 work Species Plantarum serves as the internationally accepted starting point.

[1] Linnaeus's pioneering work in botanical data management involved innovative paper-based technologies to handle information overload.

He used interleaved books, index cards, and systematic filing systems to catalogue species and maintain extensive notes on various genera.

His annotations included details on the medicinal and economic uses of plants, reflecting his broader goal of utilizing natural resources efficiently.

[11] Linnaeus designed functional herbarium cabinets with adjustable shelving, allowing for dynamic and flexible organisation to accommodate new discoveries and rearrangements.

[4] The Linnaean Herbarium shares similarities with other pre-Linnaean and early 18th-century collections, such as those of William Sherard, Hans Sloane, Paul Hermann, and Francesco Cupani.

Unlike some other collections that underwent significant rearrangements over time, the Linnaean Herbarium remains largely in its original form, making it a particularly valuable resource for understanding 18th-century botanical practices.

In 1794, David Hosack acquired one of the few Linnaean specimen collections in America, obtaining duplicates from James Edward Smith during his London studies.

[3] Due to its immense scientific and historical value, the Linnaean Herbarium is now carefully preserved in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment beneath Burlington House in London.

[1] In 1958–59, a more detailed photographic record was created in collaboration with the International Documentation Centre AB, Sweden, available in microfiche form.

This monumental work, representing more than 25 years of research and collaboration with hundreds of botanists worldwide, meticulously designated type specimens for over 9000 plants named by Linnaeus, adhering to the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature.

[16] The Linnean Society of London has made the Linnaean Herbarium accessible online, allowing researchers worldwide to study the specimens digitally.

It highlights the importance of Linnaean specimens as type material for plant names, underlining their continued relevance in modern botany.

This project aims to provide a comprehensive catalogue of type designations for all Linnaean plant names, necessary for clarifying their application in botanical nomenclature.

This resource provides information on place of publication, stated provenance, type specimens or illustrations, and current taxonomic placement for each name.

Through typification research, botanists determined that the definitive specimen (lectotype) that Linnaeus used to describe this species is preserved in the Clifford Herbarium at London's Natural History Museum.

The authors' work involved examination of original specimens, illustrations, and Linnaeus' writings to establish lectotypes and epitypes for these names, often navigating complex issues of interpretation and nomenclature.

[1] Linnaeus's method of keeping herbarium sheets unbound in cabinets allowed for a flexible and dynamic system of botanical classification.

These herbaria, though smaller than the main collection in London, are significant because they often contain type specimens and provide additional context for Linnaeus's work.