Treaty of Lisbon

[4] Opponents of the Treaty of Lisbon, such as former Danish Member of the European Parliament (MEP) Jens-Peter Bonde, argued that it would centralize the EU,[5] and weaken democracy by "moving power away" from national electorates.

[9] After a "period of reflection", member states agreed instead to maintain the existing treaties and amend them, to bring into law a number of the reforms that had been envisaged in the abandoned constitution.

[10][11] The need to review the EU's constitutional framework, particularly in light of the accession of ten new Member States in 2004, was highlighted in a declaration annexed to the Treaty of Nice in 2001.

The Laeken declaration of December 2001 committed the EU to improving democracy, transparency and efficiency, and set out the process by which a constitution aiming to achieve these goals could be created.

While the majority of the Member States already had ratified the European Constitution (mostly through parliamentary ratification, although Spain and Luxembourg held referendums), due to the requirement of unanimity to amend the treaties of the EU, it became clear that it could not enter into force.

The meeting took place under the German Presidency of the EU, with Chancellor Angela Merkel leading the negotiations as President-in-Office of the European Council.

[15] The European Round Table of Industrialists (ERT) Members contributed to the preparation of the Lisbon Agenda, which sought to make Europe the 'most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world' by 2010.

ERT Members constantly stressed the need for better performance by national governments towards achieving the Lisbon targets within a specified timeframe that otherwise risked remaining beyond Europe's grasp.

In subsequent years, ERT regularly contributed to the debate on how to ensure better implementation of the Lisbon Agenda across all EU Member States, including on ways to foster innovation and achieve higher industry investment in Research & Development in Europe.

In addition, it was agreed to recommend to the IGC that the provisions of the old European Constitution should be amended in certain key aspects (such as voting or foreign policy).

Among the specific changes were greater ability to opt out in certain areas of legislation and that the proposed new voting system that was part of the European Constitution would not be used before 2014 (see Provisions below).

[22] That included giving Poland a slightly stronger wording for the revived Ioannina Compromise, plus a nomination for an additional Advocate General at the European Court of Justice.

[23] Despite these concessions and alterations, Giscard d’Estaing stated that the treaty included the same institutional reforms as those in the rejected Constitution, but merely without language and symbols that suggested Europe might have 'formal political status'.

Prime Minister Gordon Brown of the United Kingdom did not take part in the main ceremony, and instead signed the treaty separately a number of hours after the other delegates.

Under the original timetable set by the German Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the first half of 2007, the Treaty was initially scheduled to be fully ratified by the end of 2008, thus entering into force on 1 January 2009.

The first months under Lisbon arguably saw a shift in power and leadership from the commission, the traditional motor of integration, to the European Council with its new full-time and longer-term President.

[43] The earlier rules for QMV, set in the Treaty of Nice and applying until 2014, required a majority of countries (50% / 67%),[clarification needed] voting weights (74%), and population (62%).

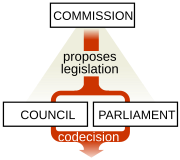

[44] The treaty instructs that Council deliberations on legislation (that include debate and voting) will be held in public (televised), as was already the case in the European Parliament.

This makes the president the lynchpin of negotiations to find agreement at European Council meetings, which has become a more onerous task with successive enlargement of the EU to 28 Member States.

It has a key role in appointments, including the commission, the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and the members of the Board of the European Central Bank; the suspension of membership rights; changing the voting systems in the treaties bridging clauses.

Following the first Irish referendum on Lisbon, the European Council decided in December 2008 to revert to one Commissioner per member state with effect from the date of entry into force of the Treaty.

[50] The person holding the new post of High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy automatically becomes also a Vice-President of the Commission.

The High Representative is Vice-President of the Commission, the administrator of the European Defence Agency but not the Secretary-General of the Council of Ministers, which becomes a separate post.

[17][51] The High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy is in charge of an External Action Service also created by the Treaty of Lisbon.

In the Lisbon Treaty the distribution of competences in various policy areas between Member States and the Union is explicitly stated in the following three categories: A proposal to enshrine the Copenhagen Criteria for further enlargement in the treaty was not fully accepted as there were fears it will lead to Court of Justice judges having the last word on who could join the EU, rather than political leaders.

There have been several instances where a territory has ceased to be part of the Community, e.g. Greenland in 1985, though no member state had ever left at the time the Lisbon Treaty was ratified.

Instead, the European Council may, on the initiative of the member state concerned, change the status of an overseas country or territory (OCT) to an outermost region (OMR) or vice versa.

Under the Treaty of Lisbon, the limitations on the powers of the Court of Justice and the commission would be lifted after a transitional period of five years which expired on 30 November 2014.

In order to avoid submitting to the jurisdiction of the Court of Justice and to enforcement actions by the commission, the UK negotiated an opt-out which allowed them the option of a block withdrawal from all third pillar measures they had previously chosen to participate in.

The European Council may, on the initiative of the Member State concerned, adopt a decision amending the status, with regard to the Union, of a Danish, French or Netherlands country or territory referred to in paragraphs 1 and 2.