List of Marconi wireless stations

The Canadian Marconi Company operated manufacturing facilities at Montreal, Quebec and in 1919 had established on an experimental basis the first commercial broadcast radio station, XWA.

As the original, powerful spark gap transmitters would create large quantities of electrical interference, stations could not transmit and receive at the same time - even if different wavelengths were used.

By 1913, the increasing amount of transatlantic radio telegraph traffic required that existing half-duplex operation be upgraded to a link which could carry messages in both directions at the same time.

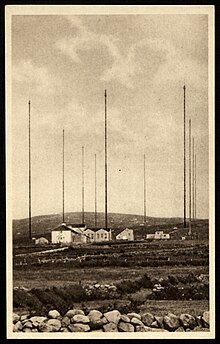

[11] Antennas for longwave radio reception were to occupy huge amounts of land at these sites; while Lee de Forest's work had produced a vacuum tube (or "Audion") as early as 1906, many key advances in electronic amplifiers (which would allow smaller receiving antennas and more efficient transmitter designs) would only be made once improved communications became a military necessity during World War I.

The design and construction of tuned circuits able to separate radio signals transmitted and received at different frequency and wavelength had also shown great improvement.

By 1926 Marconi would be able to use shortwave radio to link the British Empire, making the former long-wave transatlantic service and its Louisbourg receiving station obsolete.

[13] On 29 May 1914 the Pointe-au-Père Marconi station received an SOS call from the RMS Empress of Ireland, a Canadian passenger liner which, surrounded by fog, had been hit by Norwegian coal freighter SS Storstad.

"May have struck ship... listing terribly" reported Marconi operators Edward Bamford and Ronald Ferguson,[14] notifying rescuers on shore of their position twenty miles seaward of Rimouski[15] as the vessel rapidly took on water.

On 27 March 1899, Marconi transmitted from Wimereux, Boulogne, France the first international wireless message which was received at the South Foreland Lighthouse near Dover, United Kingdom.

In 1902, a Marconi telegraphic station was established in the village of Crookhaven, County Cork, Ireland to provide marine radio communications to ships arriving from the Americas.

[19] Due to destruction caused by the Irish Civil War in 1922, traffic formerly carried at Clifden was permanently redirected via Marconi's new station at Ongar in Essex, a link which remained in service until replaced by the Canadian shortwave beam circuit in October 1926.

The stations were not idle in the interim, however, having been appropriated by the British Admiralty almost immediately upon outbreak of the Great War and kept in constant activity as key components of the allied communication system until the Armistice of November 1918.

The first west to east voice transmission had already been achieved by Bell Systems engineers from the US Navy station at Arlington Virginia to the Eiffel Tower in October 1915.

[22] On 13 November 1910 the first radio message to Africa was sent from a radiotelegraph station at Coltano, Italy and received in Massawa (then part of the Italian colony of Eritrea).

Italy's King Vittorio Emanuele officially opened the station in 1911, at which time messages were sent from Coltano to Glace Bay (Canada) and Massaua.

[23] The first transatlantic radio message, transmitted from Marconi's Poldhu, Cornwall transmitter, was received 12 December 1901 at Signal Hill, St. John's, Newfoundland.

Subsequent efforts at transatlantic communications would use Cape Breton, Nova Scotia as a Canadian terminus due to the Anglo-American Telegraph Company's entrenched monopoly in the Dominion of Newfoundland.

By the 1930s, original spark gap transmitter equipment at these sites would have been removed due to severe interference caused to broadcast radio operations.

Exploiting a strategic location at the south-easternmost part of Newfoundland, the Cape Race (VCE) station could serve as a vital first point of contact for arriving ships in the New World, as well as providing telegram service to transatlantic passenger liners.

[30] Messages received from travellers crossing the Atlantic could be relayed in a timely fashion to much of North America, including major cities such as New York, long before a ship's arrival.

A copy of April 1912 station logs (documenting communication between Cape Race and Titanic) appear in the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The Cape Ray (VCR) and Belle Isle (VCM) stations, which played a similar role, served ocean-going liners in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

On 1 February 1912 a new Marconi station erected at Aranjuez near Madrid, Spain transmitted a message from King Alfonso which would be received at Poldhu, Cornwall, England for delivery to the London correspondent of the New York Times.

Initial attempts to deploy land-based military radio were problematic, but the five Marconi installations in March 1900 on naval cruisers HMS Dwarf, Forte, Magicienne, Racoon and Thetis proved successful.

[34] By 1912, Marconi stations covered Aden, Algeria, Australia, Azores, Belgium, Brazil, Burma, China, Curaçao, France, French Guiana, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Jamaica, Mexico, Morocco, Netherlands, Norway, Romania, Russia, Senegal, South Africa, Sweden, Tobago, Trinidad, Uruguay, Zanzibar, and the Pacific Ocean.

A message received in 1910 in the UK from Marconi-equipped ship SS Montrose, then en route to Canada, would prove key to the arrest of fugitive Hawley Harvey Crippen.

[39] In 1898, Marconi began tests of ship-to-shore communication between Trinity House Lighthouse, Dover, Kent, England and the East Goodwin lightship.

A station at Tetney, Lincolnshire, England, constructed as part of the Imperial Wireless Chain linking the nations of the British Empire, established shortwave communications with Australia in April 1927 and India in September 1927.

[55] KPH has been preserved by volunteer members of the Maritime Radio Historical Society and is operated at weekends and on special occasions such as International Marconi Day and the anniversary of the "end of commercial Morse code in America."

"[59] A Marconi station at Kahuku on the North Shore of Oahu, Hawaii was later operated by RCA; the site was re-purposed as an air base during World War II and is now abandoned.